‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

As we publish Dylan Thomas’s Collected Poems 1934-1952, Sally Minogue reflects on the riches to be found there.

Sculpture of Dylan Thomas by Eric de Maré

Most of you reading this blog will already know lines from or titles of some of Dylan Thomas’s poems. In the majority of his poems, the title is simply the first line of the poem, and he has a genius for first lines. They stick in the mind and the memory. ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’, ‘In my craft or sullen art’, ‘It was my thirtieth year to heaven’, ‘Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs’, ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower’ – these are a few of his first lines, and they also belong to some of his best-known poems. Their appeal is immediately evident. They are almost all conversational in tone, yet they seize us too with an unusual twist of vocabulary: ‘sullen art’, ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’, ‘thirtieth year to heaven’, ‘green fuse’. Conversational – but also unexpected. The vocabulary itself is disarmingly simple: no less than 34 of the words in those lines are monosyllables (leaving 6 with two syllables, and only one with 3). So no wonder that they are easy to remember. The poet has drawn us in with what seems the simplest, most personal, even intimate form of address. Yet those surprise words, or the surprise of their multiple connotations, turning the words round on themselves, mean that by the end of the poem we too have to double back, to think again. ‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

Both the memorable simplicity, and the dual doubling-back aspect, are characteristic of Thomas’s poetry as a whole, and this may be why his poetry has been seen on the one hand as easily accessible and on the other as obscure – and sometimes condemned on both counts! None of the poems whose first lines I mention above could be called obscure. But neither is their meaning always as plain or simple as those colloquial openings suggest. I want to argue that both the direct and the less direct aspects of Thomas’s poetry are important in our enjoyment of his work. But above all I want to stress that word enjoyment. Thomas’s most remarkable and consistent achievement as a poet writing in a period of existential uncertainty, in the aftermath of the First World War and the midst of the Second World War, and then in the knowledge of the holocaust, is that he celebrated life. He did that with a gusto that is embodied in the pleasure he takes in poetic language, and which found its most unfettered expression in his joy in the natural world and the larger movements of life itself. Even when he is urging us to ‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light’, there’s an extraordinary energy in his fury against that dying, and it is the repeated ‘light’ which ends alternate verses and is the last word of the poem.

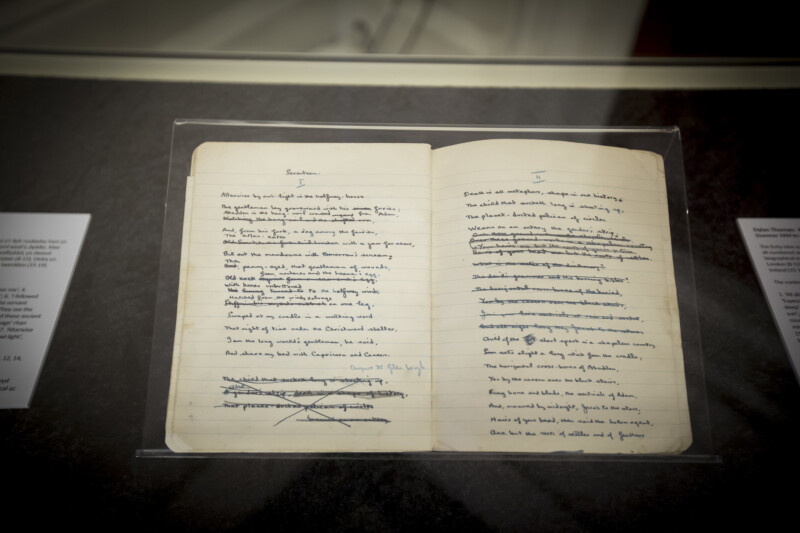

Dylan Thomas’s 5th notebook on display at Swansea University

The Collected Poems follows the trajectory of Thomas’s writing life; it is almost wholly chronological, following the run of his published collections. As he himself put it in November 1952 at the point of publication, ‘This book contains most of the poems I have written, and all, up to the present year, that I wish to preserve’. It is the summation, then, of his poetry-writing life. Of course, he was not to know when he wrote those words that there would be no more poetry. Thomas was 38 – roughly the halfway point of a standard life – so there is a poignancy in the unwritten ‘second half’ which reverberates into the emptiness when we close Collected Poems. That said, this is a remarkably rich and substantial oeuvre for a short life, in part because Thomas started writing poetry when he was only 15. Well, many of us have done that, and it’s usually adolescent nonsense. But at that age Thomas began to enter what he saw as finished poems in a set of exercise books, now known as his Poetry Notebooks. Scholarship on Thomas’s poetry has been based on the four known Notebooks, dating from April 1930 to April 1934, with Notebooks three and four, 1933-1934, written between the ages of 18 and 19, providing the rich seam that Thomas mined when he burst on to the literary scene. In 2014, however, a previously unknown fifth Notebook suddenly came on to the market, containing drafts of a significant 10-poem sonnet sequence in Collected Poems, ‘Altarwise by Owl-light’, originally published in his second collection, Twenty-Five Poems.[1] This Notebook dates from April 1934 to August 1935, when Thomas was between the ages of 19 and 20. What the Poetry Notebooks reveal is that a substantial number of the poems he published in his first two collections, 18 Poems (1934) and Twenty-Five Poems (1936), were written before he was 21, and a considerable number date from his teens. Of course, he revised and redrafted for later publication but sometimes the published poem is close to its Notebook form. One such is the famous ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower’, one of the poet’s earliest celebrations of the life force, here driving the ink through the poet’s pen in the same way that light-synthesising chlorophyll drives growth through the plant’s stem and leaves, ultimately producing the flower. This poem was drafted into Notebook 4 in October 1933 when the poet was still only 19, published in the Sunday Referee on October 29th 1933 just after his 20th birthday, and won that paper’s annual best poem prize – which launched his poetic career, since the prize was publication of a collection. That collection was 18 Poems, published in December 1934.

I specify these dates to remind us of Dylan Thomas’s extraordinarily precocious talent. The first poem he published in a national journal (the New English Weekly, May 1933), even before ‘The force that through the green fuse’, was ‘And death shall have no dominion’, still one of his best-known and most powerful poems. (Unusually, this poem was not included, as it could have been, in his first collection 18 Poems, but did appear in Twenty-Five Poems.) It is not that being precocious is in itself a good; it is rather that these early poems are in themselves so good (rare in any poet’s output). The proof of that is that they have remained fresh in the public imagination to this day. And perhaps the youth of their author gives them that particular intensity and freshness which still move us today. ‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

‘Deaths and Entrances’. Published by Dent & Sons London 1946

Thomas then drew on his Poetry Notebooks for his important first two collections, represented in Collected Poems from pp. 9-78, as he did for his mid-way and mixed-genre collection, The Map of Love (1939), containing both stories and poems. (The poems from that collection can be found in this volume from p. 79 to p. 101.) But at this point Thomas’s poetry takes a different turn. The Poetry Notebooks and the imaginative furnace of his youth are left behind as the Second World War creates both a personal crisis for him as a writer, and turns his poetic imagination in a darker and more profound direction. Deaths and Entrances (1946) is the collection that results, represented in Collected Poems from p. 102 to p. 161. The second poem in the wartime Deaths and Entrances is ‘A Refusal to Mourn the Death, By Fire, of a Child in London’. That uncompromising title tells us that Thomas was not about to write a conventional elegy, rather he was refusing to do so. In this and other poems in that important collection, including the eponymous ‘Deaths and Entrances’ (pp. 119-120), ‘Ceremony After a Fire Raid’ (pp. 131-133), and ‘Among those Killed in the Dawn Raid was a Man Aged a Hundred’ (p. 137), Thomas takes a complex stance, refusing standard consolations yet through the poetry’s own grandeur somehow monumentalizing the dead, and even showing their deaths as redemptive. These are powerful and complicated poems, answering to a historical moment, and are in my view some of Thomas’s best work. Yet remarkably, in the very same collection, and also to be regarded as amongst that best work, are two poems of celebration of the natural world and lyrical joy in the very act of being alive: ‘Poem in October’ and ‘Fern Hill’ (the final poem in the collection). ‘Poem in October’ is one of several birthday poems – almost its own separate genre in his oeuvre – which at times more full-throatedly, at times more mutedly, sing a paean to being alive. These poems also take stock at key points of the poet’s own life of himself both as man and writer, and so are illuminating markers through the Collected Poems. ‘Fern Hill’ is simply a joyous catching-hold of that moment of being ‘young and easy’, ‘happy as the grass was green’, ‘green and carefree’, ‘green and golden’, and ‘happy as the heart was long’. The repeated ‘green’ takes us back to ‘the green fuse’. A small note of trouble enters in at the very end – ‘Time held me green and dying’ – but as ever the life force and the poetry force triumph: ‘Though I sang in my chains like the sea’.

The last few poems in the volume are Thomas’s own last poems and include what would be his final birthday poem, ‘Poem on his birthday’ (pp. 168-171), a poignant mixture of the valedictory and the stubbornly life-affirming. Here as ever in his best poems the verve and sheer imaginative play of the language gives the poem a buoyancy and optimism even as it pronounces otherwise:

…. The closer I move

To death, one man through his sundered hulks,

The louder the sun blooms

And the tusked, ramshackling sea exults (p. 171)

‘Over Sir John’s Hill’ (pp. 166-167) has some of the best writing he ever did about the natural world. We can see the influence of Gerard Manley Hopkins, but none of that poet’s agonizing over his love of the beauty of the world:

Flash, and the plumes crack,

And a black cap of jack-

Daws Sir John’s just hill dons, and again the gulled birds hare

To the hawk on fire, the halter height, over Towy’s fins,

In a whack of wind. ‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

The author’s well-read copy of ‘Collected Poems’.

This rhapsodic writing about nature, and the sheer joy of being alive, has not always fitted easily into the poetic aesthetic of the last 70 years since Dylan Thomas’s death. Spareness of language, suspicion of over-emotionality, an inherent scepticism and a tendency to pessimism, these were the watchwords of the poetry which, with a few notable exceptions, dominated the latter part of the twentieth century, and indeed that fitted with the mood of the times. In this, Thomas’s Welsh origins have worked against him in two directions. English academia has been suspicious of what they have characterised as bombast and over-emotionality of content and language (seen, unstatedly, as characteristically Welsh), whilst Welsh academia and culture have proclaimed Thomas not Welsh enough because he eschewed the Welsh language. In my Introduction to Collected Poems 1934-1952, I propose an alternative non-Anglocentric poetic tradition that might have thrived if Thomas had survived and continued writing, rather than the post-Modernist, post-Movement tradition against which he has been unfairly measured. Thomas reaches back to a Romantic Wordsworthian tradition, but he reconfigures it with a twentieth-century eye and voice, without being embarrassed about a full-blooded embrace of the pleasures of language and of life. Contemporary beneficiaries of that ghost tradition are poets such as Daljit Nagra, who has said that Thomas’s ‘shadow looms happily over my work’, and Seán Hewitt, whose language is rhapsodic and philosophical in one and the same breath.

The very last poem that Dylan Thomas wrote is actually the first poem in this volume since it is the poem that he wrote to act as a prologue to the Collected Poems, and is simply entitled ‘Author’s Prologue’ (pp. 5-7). There is a nice symmetry about his last poem being his first, something he would have taken pleasure in given his sensitive understanding of the circularity of the life process, and the inevitability in it of death. But ‘Author’s Prologue’ has few intimations of mortality; rather it is an unashamed call to arms for poetry, for nature, and for life. It is also an intimate celebration of his own locale, Laugharne and its surroundings. For him the particular was important, because it spoke of and had its special place in the large: ‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

Hark: I trumpet the place,

From fish to jumping hill! Look:

I build my bellowing ark

To the best of my love

As the flood begins …

My ark sings in the sun

At God speeded summer’s end

And the flood flowers now. (pp. 6-7)

The poet is nothing less than Noah, poetry is the ark, and it will carry us all on the flood and keep us alive. A high ambition, but one that I think Dylan Thomas fulfils.

Useful websites are www.discoverdylanthomas.com and www.dylanthomas.com.

See also: Michael Sheen performs ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’ on YouTube

Seán Hewitt’s second poetry collection, Rapture’s Road, is just out from Jonathan Cape; his first, also Cape, was Tongues of Fire. Daljit Nagra’s most recent collection is indiom; his first collection was Look We Have Coming to Dover. Both are published by Faber.

Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood (including his short story collection, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog) is also recently published by Wordsworth Editions and can be found here: Under Milk Wood

[1] This was purchased by Swansea University and eventually published in 2021 by Bloomsbury.

Main image: Taf Estuary, Laugharne, Carmarthenshire. Credit: Simon Whaley Landscapes / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Sculpture of Dylan Thomas at the Royal Festival Hall, South Bank, Lambeth, London, c1951-1962. Artist: Eric de Maré Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: The Dylan Thomas fifth notebook, on display at the Council Chamber in the Abbey at Swansea University in May 2015. © James Davies

Image 3 above: Deaths and Entrances Poems by Dylan Thomas. Published by Dent & Sons London 1946 Credit: Contributor: Antiques & Collectables / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4: Image courtesy of Sally Minogue

‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

‘Time held me green and dying Though I sang in my chains like the sea’

Books associated with this article

Collected Poems 1934-1952

Dylan Thomas