Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

‘The aim of an artist is not to solve a problem irrefutably, but to make people love life in all its countless, inexhaustible manifestations’ (Count Leo Tolstoy)

In this final blog on a trio of great Russian novels, Sally Minogue suggests reasons for thinking that Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is the greatest of the three.

The opening sentence of Anna Karenina (1878) is justly famed: ‘All happy families resemble one another, but each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ (p. 1) But how many people have had to look back to the text – as I confess I have myself – to check which way round the aphorism goes? If Tolstoy had written it the other way round, asserting that all unhappy families are alike etc, wouldn’t we have accepted this just the same? My point here is that the novelist’s assertive voice, announcing itself so confidently from the opening moment, subdues the reader to its narrative and conceptual authority, and as we read on, we interpret everything that follows in its light. The same might be said of Jane Austen’s similarly famous opening to Pride and Prejudice, where the first four words, ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged’, brook no disagreement from the reader. Austen’s full sentence (‘It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife’) is of course ironic, but likewise it is framed to make us accept the irony, which again leaves no room for our inserting any disagreement.

I am labouring this point rather heavily because the central power of Anna Karenina derives from the way in which Tolstoy as narrator embodies ungainsayable authority, and by that very means also carries the reader with him when he shifts that authority to a different way of looking at the world. Empathy is at the heart of this novel, and even as Tolstoy seems to set moral problems for his characters (and so also for us) at every turn, he always sets them in the context of human emotions, which drive the tragic impulses of the novel and also strike its counterpointing notes of optimism. Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

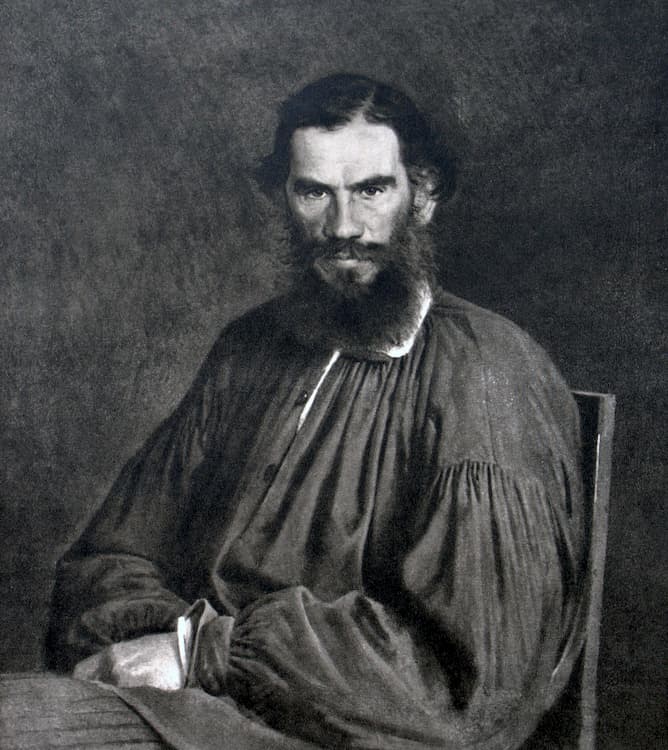

Tolstoy 1873

The title Anna Karenina acknowledges its central eponymous heroine, and this is particularly interesting in comparison to the Dostoevsky and Turgenev novels we’ve looked at, where patriarchy dominates. But the complexity of the novel and its shifts of viewpoint derive not from one unitary story but from several interlocking ones, each based on a set of characters, and each underpinned by a marriage – either happy or unhappy. The marriage of Prince Stepan/Stephen Arkadyevich Oblonsky (Stiva/Steve) to Darya Alexandrovna (Dolly) is the first we meet and seems to bear most of the weight of that opening sentence. That marriage, which has been happy, is, as the novel opens, now unhappy on account of Oblonsky’s affair with the family governess, which has been revealed to Dolly. Tolstoy, keen to begin in medias res, passes over lightly the fact that it is the governess, but clearly this is a particular assault by Oblonsky on his own family circle. In an utterly masterly first few pages, Tolstoy sketches in the character of Oblonsky with a light wit and a forgiving though all-seeing eye. As readers we understand immediately that the governess was probably chosen for convenience; she was to hand. Oblonsky is one of those men, in life as in the novel, who is going to sail through every disaster, because he can’t quite see that any disaster is happening in the first place. And even if it were, surely doesn’t he deserve that all will come right in the end? He is even a little aggrieved with Dolly’s distress, thinking she ought to be lenient with him:

Oblonsky was always truthful with himself. He was incapable of self-deception and could not persuade himself that he repented of his conduct. He could not feel repentant that he, a handsome amorous man of thirty-four, was not in love with his wife, the mother of five living and two dead children and only a year younger than himself. He repented only of not having managed to conceal his conduct from her. Nonetheless he felt his unhappy position and pitied his wife, his children, and himself. (p. 3)

He may be always truthful with himself, but the unfilled spaces in Tolstoy’s description make it clear that Oblonsky’s truth is limited to his own sphere of self-interest. No room to consider that Dolly might at any time think or feel as he does; she is a woman. These early pages make evident the combination of sympathy and devastating clear-sightedness which is Tolstoy’s signature. Even as we raise our eyebrows at that ‘five living and two dead children’, we feel the beneficence of the narrator’s gaze on Oblonsky, and we know he’ll come out of this unharmed. It’s not that Tolstoy approves of him; he simply sees that the Oblonskys of the world thrive.

Prince ‘Stiva’ Oblonsky is the brother of Anna Arkadyevna Karenina – our heroine; it is Anna who persuades Dolly to forgive her Stiva. Anna could not be more unlike her brother. Her own marriage to Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin is ostensibly happy, or at least successful, but as we’ll discover, it does not give her what she wants, with the exception of her much-loved son the eight-year-old Sergei/Seryozha. When she is first attracted to Count Alexei Kirillovich Vronsky, she sees how powerful her feelings are and tries to resist them, fleeing back to St Petersburg and her husband. Where Oblonsky’s desires (beyond the firm circle of his family) are shallow and replaceable, Anna’s run deep and are serious. Tolstoy’s matching of these two siblings and his weighing of the married man’s light affair against the married woman’s deeply considered infidelity is in itself remarkable within the depiction of such a patriarchal society. In my view he maintains our sympathy with Anna to the end, in part because she takes her relationship with Vronsky so seriously and is strongly exercised by its threat to her marriage, not for social reasons but because of the personal costs for all concerned. This is part of Tolstoy’s original intention in the novel, recounted in his wife Sofia’s Diary, February 24th 1870: ‘He told me he had the idea of writing about a married woman of noble birth who ruined herself. He said his purpose was to make this woman pitiful, not guilty.’ (Quoted in the Introduction, p. ix)

The third marriage, which does not take place until the latter part of the novel, but which is signalled in these early stages, is that of Constantin Dmitrich Levin (Kostya) to Dolly’s younger sister Kitty (Princess Ekaterina Alexandrovna Shcherbatskaya, but almost exclusively referred to as Kitty). Kitty, who is only 18, refuses Levin’s first proposal as she believes that Vronsky is in love with her and is about to make her an offer. That idea is soon knocked off course by Vronsky’s passion for Anna, but the narrative makes clear that Vronsky’s intentions toward Kitty were never serious. His seriousness is reserved for Anna. Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

Tolstoy and his family at Yasnaya Polyana

We begin to see, through these interweaving and contrapuntal relationships, which are also intertwined at the level of genealogy, aristocracy and land ownership, the way Tolstoy will gradually reveal many different attitudes towards his central subjects of love, honour, fidelity, and sexual passion, and the way these in turn interact with social norms, structures and expectations. It is Tolstoy’s great gift that while he never endorses society’s standards, he reveals their power. What is most moving in the novel is the way that even the characters who may seem to adhere most to those standards can be impelled to ignore them when their human emotions are called forth. Karenin, who sometimes seems the harsh embodiment of duty and social conformity, as when he initially refuses to let Anna go, or when he decides to divorce her but thereby to withhold her beloved son Sergei from her, has his moment of human understanding and forgiveness. He responds to Anna’s appeal to him to come to her as she believes she is dying in childbirth (with Vronsky’s child):

He was not thinking that the law of Christ, which all his life he had tried to fulfil, told him to forgive and love his enemies but a joyous feeling of forgiveness and love for his enemies, filled his soul. He knelt with his head resting on her bent arm, which burnt through its sleeve like fire, and sobbed like a child. (p. 407)

In her delirium Anna persuades her husband to not only forgive her but also to clasp Vronsky’s hands in forgiveness:

‘Karenin took Vronsky’s hands and moved them away from his face … “Give him your hand. Forgive him…”

Karenin held out his hand, without restraining the tears that were falling.’ (p. 407)

Yet Tolstoy is never sentimental or anything other than honest. Such scenes take place, yet they do not necessarily lead to a happy resolution. As a result of this scene, and his sense of Karenin taking the higher moral ground, Vronsky himself ‘felt ashamed, humiliated, guilty and deprived of the possibility of cleansing himself from his degradation.’ Here again Tolstoy wrongfoots the reader. If up to now we have regarded Vronsky as ‘a very fine sample of the gilded youth of St Petersburg’ (p. 38), and therefore not a very weighty character, now we see how he can suffer moral torments just as much as someone like Levin. In one of a number of similar passages in the novel which happen to various characters, Vronsky has a sort of living dream or nightmare where he sees the characters in his own personal drama pass before him in a phantasmagoric version of the reality he has just experienced. In this state, he sees suicide as the obvious answer. But even in this, he fails, missing his heart with the intended bullet. Karenin meanwhile, exulting in the power of his own forgiveness, and taking a special pleasure in the frail baby daughter of Anna and Vronsky, sees also that this state of being can’t last. ‘As time went on he saw more and more clearly that, however natural his position might seem to him at the time, he would not be allowed to remain in it.’ (p. 413) Thus moments of illumination, soul-searching, transcendental love and forgiveness take place in the novel, as do also moments of self-annihilation and self-deception and actions that are crazed and based on illusory thinking. But alongside these run the necessary motions of society which act on individuals just as do their inner landscapes of thought and feeling. The passionate dramas of the self which flare in the novel are interspersed with periods of what might be called existential boredom, where the key characters are caught in the business of social intercourse. This is what roots the novel in realism. Alongside such moments run moments of extreme existential awareness when a character, left (sometimes unusually) on their own is plagued by questions about the meaning of life itself. Between boredom and the terror of such moments, the business of society, relationships, marriage, family, work, all carry on. The capaciousness of the novels we have looked at allows for this breadth and Tolstoy’s novels in particular make full use of that. Though Henry James criticised them (War and Peace in particular) as ‘loose baggy monsters’, it is their very bagginess that allows for this large embrace of the banal, the social, the personal and emotional, the existential, and the business side of life. No-one does this better than Tolstoy, and while War and Peace can be argued to be the greater novel because it also includes both the sweep and the detail of history, as well as the grand subject of war, Anna Karenina is the ultimate human novel, with none of those large movements to distract us from the individual coming face to face with his or her own place in the universe and his or her own final fate. Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

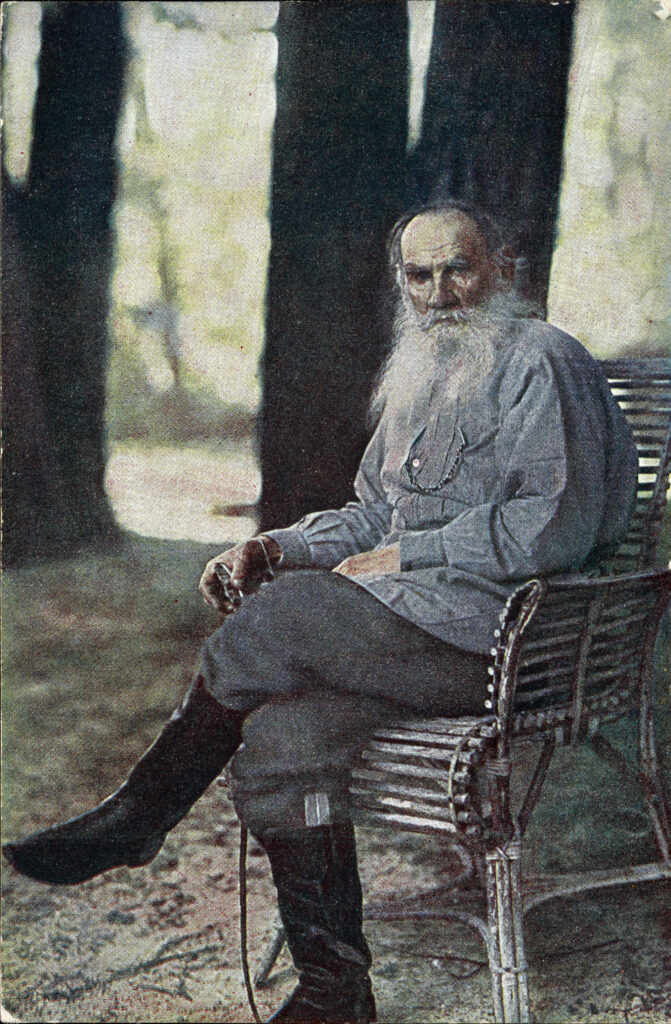

The only known colour photograph of Tolstoy 1908

Even the domestic, family-bound Dolly can admit to herself when she is (rarely) alone when travelling from Levin and Kitty’s estate to see Anna, thoughts she would not allow, or for which there simply would not be time or room, when she has been surrounded by the needs of her children and her husband. As she travels by coach from one world to the other, from the settled life of Levin and Kitty on their estate to the uncertain life of Anna and Vronsky, similarly isolated on his estate but without the solidity allowed by a place in the social system, unbidden thoughts flood in to Dolly’s mind:

And once more the cruel memory rose that always weighed on her other-heart; the death of her last baby, a boy who died of croup; his funeral, the general indifference shown to the little pink coffin, and her own heart-rending, lonely grief at the sight of that pale little forehead with the curly locks on the temples, and of the open, surprised little mouth visible in the coffin at the instant before they covered it with the pink lid ornamented with a gold lace cross.

‘And what is it all for? What will come of it all?’ (p. 601)

Dolly reflects on her life, on her moment of choice when she forgave her husband, and now wondering whether she should have started anew, and finally on Anna’s own choices. Dolly makes no moral judgements but sees all these moments of choice as equal and each full of possibility. And as readers we remember Oblonsky’s heartless reflection on ‘the mother of five living and two dead children’. (p. 3)

In this way Anna Karenina is startlingly modern, and even recalls twentieth century modernist texts. Dolly even thinks of looking in her small travelling mirror, ostensibly to check her appearance, but also to chime with her inward probings, just as Clarissa Dalloway reflects on herself in the mirror in Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, a classic modernist moment combining an outward and an inward looking. Yet Anna Karenina also shows us those moments of choice and consciousness set within a highly structured nineteenth-century society, laden with expectations of class, gender, nation, Christian responsibility – this is what makes so dramatic the eventual outcomes of individual human reflections. If marriages and the domestic structure of family life, with their day-to-day ordinariness, provide the framework of the novel, its fundamental moments of revelation are to do with death. Death punctuates the action of the novel, from the very early horror of the railway workman, caught between two trains, his body mangled terribly, to Anna’s own self-inflicted death under the wheels of a train. In any less a novel, that early proleptic death would seem heavy-handed. Yet the opening of the novel has been so lightly handled, and Tolstoy cleverly deflects our seeing this early death as a symbol of what is to come, by making Anna herself see it as a bad omen. Once that idea is put into her mouth, we can minimise it and see her as being over-dramatic in thinking it. When 700-odd pages on she herself throws herself under the wheels of a train, so much has passed that the connection does not seem heavy-handed. Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

Vivian Leigh as AK 1948

I won’t try to talk about Anna’s death; it is a passage of immense psychological subtlety where we enter her consciousness fully and are fully in sympathy with her, and each reader needs to understand it for themselves. There is a long lead up to the moment of choice, and through that Tolstoy allows us to understand Anna’s decision and also her momentary change of mind when it is too late. We know it is the wrong thing for her to do but we also know why for her it is the right thing to do, at that moment. It is the tragic dénouement of the novel but we also read it in the light of the several death scenes that have gone before it. In all of these Tolstoy makes us aware of the transcendental nature of the passage from life to death, but he also shows its quotidian nature, the way it can take days and days – or be the work of an instant, like Anna’s. It can be chosen or it can come unbidden. Even it can fail, as in Vronsky’s suicide attempt (p. 412). Two significant passages dealing with death stand out in the novel, other than that of Anna herself. One is the death of Vronsky’s mare, Frou Frou (pp. 193-197), which like the railwayman’s death prefigures that of Anna. At the time we read this painful chapter, we are still only into Part Two of the eight parts of the novel. The very distance from Anna’s final fate means that we make the connection only in retrospect. The other is the long-drawn-out death of Levin’s brother. If Frou Frou’s death and Anna’s are sudden, the opposite is the case with Nicholas Levin.

Nicholas’s death is framed within the difficulties Levin and Kitty are going through as they begin married life. Levin is annoyed that Kitty wants to accompany him to his brother’s death-bed, because he thinks she can’t bear to be alone without him; Kitty conversely wants to support her husband as he attends his brother in his last days. But when they arrive, all of that is made as nothing. Over several pages, mirroring several days, we see Nicholas dying. We see the distress of Levin, then the boredom, then the longing for the death, then the distress again:

[Levin] smelt the terribly foul air, saw the dirt and disorder, the agonizing posture of the body, and heard the groans; but he felt there was no help for it. It never entered his head to consider all these details and imagine how the body was lying under the blanket, how the emaciated, doubled-up shins, loins, and back were placed, and whether it would not be possible to place them more comfortably or do something, if not to make him comfortable, at least to make his condition a little more tolerable. A cold shudder crept down his back when he began to think of those details. … But Kitty felt and acted quite differently. When she saw the invalid she pitied him, and that pity produced in her woman’s soul not the horror and repulsion which it evoked in her husband but a need for action … and a desire to help him. (p. 490)

While the death-bed provides a coming-together between Levin and Kitty as he appreciates her understanding, for Levin it is a confrontation with the great mystery – which lasts for a full 15 pages.

Tolstoy’s grave, Yasnaya Polyana

Levin and Kitty’s marriage provides the optimistic undertow in a novel which is essentially tragic in so far as it revolves round the fate of Anna, who more than any other character carries our sympathy. Again the large span of the novel means that we can hold in our minds Anna’s mature beauty which captivates Vronsky at the ball, while the hapless Kitty can only stand by. (pp. 75-82) Yet as the novel progresses Kitty finds her full self through not only her love for Levin but also her own understanding of the world, as shown in her confidence and care during Nicholas’s death. Oblonsky and Dolly keep their marriage going, but only we as readers are privy to Dolly’s questioning of its worth. Anna and Vronsky enjoy both the ultimate happiness of a profound passion and the ultimate unhappiness of not being able to sustain that against the backdrop of a moralistic society. Yet in the interstices we see the unforgiving Karenin forgiving; we see the thoughtless Vronsky attempting a conscience-ridden suicide after that forgiveness; we see Levin working his difficult way through the many problems of trying to live a good life unmarred by falsity (an early forerunner of mauvais fois), and struggling with his minor irritations with the very Kitty whom, before marriage, he adored. We see too the underside of goodness. Anna has the insight at one point that what she must put first is her love of her son Sergei/Serezha; as long as she does that, all will be right. Yet when she is on the brink of suicide she reflects:

‘I thought I loved him [Serezha], too, and was touched by my own tenderness for him. Yet I lived without him and exchanged his love for another’s, and did not complain of the change as long as the other love satisfied me.’ (p. 753)

Everyone is shown to have their weaknesses, and if Tolstoy treats Anna more harshly than most in this respect, it is by showing her reflecting honestly on her own actions – something her brother Oblonsky, for all the protestations about his honesty, never really does.

Anna Karenina is a very different novel from the two I have discussed previously, Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons and Dostoevsky’s The Idiot. Most remarkably, it places a woman of passion and intelligence at the heart of the action, and in the midst of a society whose norms are driven by patriarchy. It is extraordinarily even-handed in the way in which it examines the various different players in that society, women and men, and it takes us into their hearts and minds to such an extent that we are, like the novelist himself, non-judgemental. It probes the lives and relationships of women and men in nineteenth-century Russia, yet we feel as though we are looking at lives like our own, in that it probes the questions we may all ask ourselves, and that most important question of all: in Dolly’s words, ‘“And what is it all for?”’ Finally, it confronts death and its frontier with life, sometimes relentlessly, whilst retaining a sense of the meaningfulness of life even where that may seem absurd. I’ll end with Levin and Kitty as they work their way towards an acceptance of each other as future husband and wife, spelling out the initial letters of the words they want to say in chalk because neither of them can quite bring themselves to utter the actual words. Afterwards Levin, suffused with happiness, wanders the streets:

And what he then saw he never saw again. Two children going to school, some pigeons that flew down from the roof, and a few loaves put outside a baker’s window by an invisible hand touched him particularly. These loaves, the pigeons, and the two boys seemed creatures not of this earth. (p. 397)

The ordinary made beautiful in all its forms, including the tragic converse. That is Anna Karenina.

——————————————————–

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina, Wordsworth Editions

Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, Wordsworth Editions

Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice, Wordsworth Editions

Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, Wordsworth Editions

Main image: Prince Volkonskiy’s house on the Yasnaya Polyana estate, where Tolstoy was born, and wrote Anna Karenina Credit: Boris Zamanskiy / Alamy Stock PhotoBoris Zamanskiy / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Portrait of Tolstoy, 1873 Credit: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Tolstoy with his family at Yasnaya Polyana. Artist: Semyon Abamalek-Lazarev Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Tolstoy photographed at his Yasnaya Polyana estate in May 1908 by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, the only known colour photograph of the writer. Credit: Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Vivien Leigh in the 1948 film directed Julien Duvivier. Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: Tolstoy’s grave in the park of his memorial estate in Yasnaya Polyana near Tula, Russia. Credit: Azoor Photo Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

For more on Tolstoy’s life and works, see: Leo Tolstoy website – (leo-tolstoy.com)

Our edition of Anna Karenina is here

Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

Tolstoy’s ‘Anna Karenina’

Books associated with this article