Ulysses: Saluting a novel like no other

February 2nd is James Joyce’s birthday – and also the 100th birthday of Ulysses! Sally Minogue salutes a novel that is like no other.

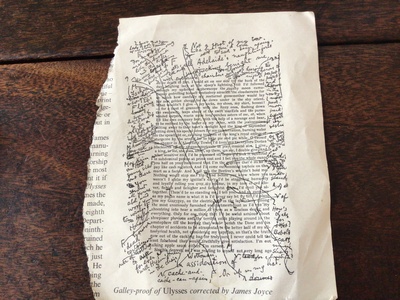

In the days of the old Reading Room at the British Museum, there used to be a small display in the public exhibition space devoted to literary manuscripts. When on theatre trips to London with my F.E. students, I made a point of taking them to see these, and in particular to see the galley-proof of a single page of James Joyce’s Ulysses, corrected by Joyce himself.

My idea was to inspire them, as I had been inspired, by the sheer rigour of a creative imagination which necessitated – at proof stage! – such a riot of emendations to a page which had already been endlessly worked over, revised and re-revised at the composition stage. I have a small photocopy of that page pinned on the wall above my writing table, though when I look at it now I also see a sort of madness. No wonder printers found Joyce difficult; but then think how difficult printers were with Joyce! The first version of his short story collection Dubliners was completed in 1905, but the complete version was not published until 1914, because it twice fell foul of printers who objected to certain stories and expletives. Its second putative publication by Maunsel and Roberts, in 1909, did reach galley-proofs, but at that stage the printers, Falconer’s, objected. This probably had more to do with perceived (and expensive) liability under the Obscenity laws rather than the enforcing of some sort of moral objection. But in spite of Joyce’s offering to reimburse the printing costs in exchange for the return of the proofs, Falconer’s refused, threatening that the proofs would be burnt, and the type broken up. Joyce did manage to rescue a copy of the proof pages, but one can only imagine his horror and fury at the idea that the work might be lost. This would not be the only time that Joyce’s pages would be consigned to the bonfire.

When we look at Dubliners now, it’s hard to imagine what stirred such strong feelings against it. Ulysses, however, is another matter.

There is plenty to upset the ordinary citizen, as was no doubt part of Joyce’s intent – not because he sought to shock, but because he objected to the whole notion of shock. This is a text that refuses any limits. In my previous blog on Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, I noted that Woolf herself, in spite of her bohemian context, and her own sexual freedom in terms of loving women, nonetheless was made uncomfortable by Joyce’s writing about the body. Joyce treats the body on a par with everything else; it is not privileged, its functions are not unnecessarily pushed to the fore – they are simply there, alongside and as important as everything else. The really excellent introduction to the Wordsworth edition, by Cedric Watts, quotes Joyce’s own words about his emerging novel:

It is the epic of two races (Israel-Ireland) and at the same time the cycle of the human body as well as a little story of a day … my intention is not only to render the myth [into the likeness of our time] but also to allow each adventure (that is, every hour, every organ, every art being interconnected and interrelated in the somatic scheme of the whole) to condition and even create its own technique. (Selected Letters, p. 271, parentheses Joyce’s own)

‘Every hour, every organ, every art being interconnected’: that is the ethic and aesthetic of Ulysses, and when we read it we have to read it in that spirit. Ulysses is uniquely capacious and all-embracing. The nearest literary thing that I can think of with the same spirit of generosity is Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, another text that gets under people’s skins.

So this is a uniquely open text, and there is no denying that Joyce’s ambition also makes it – potentially – a difficult work to read.

His mention of myth in the quotation above is a reference to the Homeric framework of the Odyssey which acts as a retaining structure for his novel. Again here Joyce reaches beyond the island of Ireland to a different civilization, an ancient time, and a foundational epic poem. What an act of genius, to equate the humble and flawed Leopold Bloom, an Irish Jew, with the wandering Ulysses, and further to refuse some of the heroics of the mythical counterpart. Molly isn’t going to be wasting time on any weaving; and Leopold, Poldy, isn’t going after the likes of Blazes Boylan – a name that says it all. The mythic structure underpins the text, but even here Joyce goes beyond it and refuses its heroic terms in favour of the anti- and sometimes mock-heroic. Reference back to the structures of the Odyssey can help the reader, but not if strenuous efforts are made to match the modern and the ancient text. Pick up resonances where you can, perhaps with the help of explanatory notes, which are available in many forms. As with the physical geography of Dublin (and the geography of London in Mrs Dalloway), the real map exists, and in Joyce’s case the myth exists, but it is what he maps on to it that really matters. And that is the human in all its forms.

The first section of Ulysses, which introduces us to Stephen Dedalus, is formed of three chapters, the third of which begins ‘Ineluctable modality of the visible’ (34) – a phrase which charmed me on my first reading (though I didn’t really understand it) and which still seems to me to be central to the potency of the novel. As that younger reader, I probably fancied myself something like Stephen, caught in the life of the mind. At that point I didn’t understand that Joyce was making fun of Stephen, even as he saw him as his own alter ego. But what Stephen also embodies, in that phrase and in his reflections during these three chapters, is a serious engagement with life. As yet it is principally the life of the mind – his puzzle is that everything that is seen must pass through the mind and be commuted by it, but at the same time the mind can act only on the sensory world. Stephen pursues this as a philosophical question, that of solipsism – does the material world exist outside the perception of it, or is it determined by that perception? This question is at the heart of modernist writing, which explored as never before the multiple nature of reality as refracted through individual consciousnesses. If multiple consciousnesses mean multiple realities, then can there be still a monolithic material reality?

Stephen’s own hesitant answer, as he walks along the strand beset by thoughts of failing his mother, comparing himself with Hamlet, hearing Parisian echoes underrunning Dublin street music (for there is also an ‘ineluctable modality of the audible’, 34), is this:

Stephen closed his eyes to hear his boots crush crackling wrack and shells. … My ash sword hangs at my side. Tap with it: they do. My two feet in his boots are at the end of his legs, nebeneinander. Sounds solid: made by the mallet of Los Demiurgos. Am I walking into eternity along Sandymount strand? Crush, crack, crik, crick. …

Open your eyes now. I will. One moment. Has all vanished since? If I open and am for ever in the black adiaphane. Basta! I will see if I can see.

See now. There all the time without you: and ever shall be, world without end. (34)

Stephen’s solution, and possibly Joyce’s too, is in the apprehension of the physical world.

Joyce playfully has him imitate Dr Johnson’s refutation of Bishop Berkeley’s argument that the material world exists only in the idea of it, by kicking the stone in front of him and declaiming, ‘I refute it thus!’ Crush, crack, crik, crick is Stephen’s equivalent, as is the fact that when he opens his eyes the world is, reassuringly, still there. No matter that the idealist view would simply accommodate these ‘sensations’ – Joyce is I think laying a marker down here, even if it is through the ironised intellectuality of Stephen. The physicality of the world, the human apprehension of the world through the body (and the brain is of course one organ of the body), lie at the centre of what he celebrates in Ulysses. It is not that he ignores the possible void that Stephen imagines (‘If I open and am forever in the black adiaphane’ – opaque, i.e. the dark). But in contrast with Virginia Woolf’s modernist explorations, it is not at the centre of his imagination. Woolf sees life as ‘a little strip of pavement over an abyss’ (Diary, October 25th 1920), and her great achievement is to evoke that existential abyss. Joyce’s writing is in the service of the life thronging above it. That is life in all its manifestations, and so death is there throughout; but his multiple expressions of multiple consciousnesses are always in the pursuit of the fullest representation possible of a many-layered lived reality. Joyce is ultimately a realist.

While this may seem at odds with the sometimes wildly experimental nature of the writing, those experiments are constantly trying to get at all possible modes of perception and apprehension. The central consciousness in the novel, and the one that occupies the central second part of the novel, and ‘chapters’ 4-15, is that of Leopold Bloom, Ulysses himself. Through him we see played out Joyce’s many attempts to give a language and form to the world, to reflect the many ways in which the world can be experienced. And here Joyce lays down another marker. The first ‘chapter’ of section 2 begins with his celebrated description of Bloom’s appetite for offal:

Mr Leopold Bloom ate with relish the inner organs of beasts and fowls. He liked thick giblet soup, nutty gizzards, a stuffed roast heart, liver slices fried with crust-crumbs, fried hencods’ roes. Most of all he liked grilled mutton kidneys which gave to his palate a fine tang of faintly scented urine. (48)

If Stephen’s is the life of the mind, Leopold’s is unquestionably and unashamedly the life of the body. Food is celebrated and likewise the expulsion of food through excretion is celebrated. And all alongside are Bloom’s thoughts, reflections, feelings and expressions, more various than Stephen’s as befits his longer and harder experience. The mind is not missing with him, but it is rooted in the body. We move with him to the pork butchers where ‘the shiny links packed with forcemeat fed his gaze and he breathed in tranquilly the lukewarm breath of cooked spicy pig’s blood’. (51) Yet only a page or two later:

A barren land, bare waste. Vulcanic lake, the dead sea: no fish. Weedless, sunk deep in the earth. …It lay there now. Now it could bear no more. Dead: an old woman’s: the grey sunken cunt of the world.

Desolation.

Grey horror seared his flesh. (54)

This is the equivalent of Woolf’s ‘there was an emptiness about the heart of life; an attic room’ (Mrs Dalloway) But soon Bloom is up and away: ‘Quick warm sunlight came running from Berkeley Road, swiftly, in slim sandals, along the brightening footpath’. (54) The grey sunken cunt of the world is supplanted by the brightness of youth. This overt gendering may today raise objections; I shall return to this at the end of the blog.

The central narrative thrust of the first part of the Bloom section is provided by the funeral of Paddy Dignam, which underlies both the breakfast scene and the concomitant lavatory scene. Dignam’s funeral takes Bloom out onto the streets of Dublin and to the itinerary which will lead to his crucial meeting with Stephen – the ‘father’ Ulysses meeting with the ‘son’ Telemachus. Bloom has two deaths to think about beyond, but recalled by, Dignam’s; one his father’s suicide, the other the early death of his son Rudy. His thoughts of both are fleeting and intermittent, too hard to face full on. He is readier to dwell on death in its specifics, and again these are bodily:

I daresay the soil would be quite fat with corpse manure, bones, flesh, nails, charnelhouses. Dreadful. Turning green and pink, decomposing. Rot quick in damp earth. The lean old ones tougher. Then a tallow kind of a cheesy. Then begin to get black, treacle oozing out of them. Then dried up. Deathmoths. Of course the cells or whatever they are go on living. Changing about. Live for ever practically. Nothing to feed on feed on themselves. (97)

This passage, grim as it is, is in and of itself somehow optimistic, turning as it does towards a sort of unending life, and the language too is full of vitality. Eventually Bloom, even with the depth of his sadness about his lost son Rudy, reverts to the pull of life:

Plenty to see and hear and feel yet. Feel live warm beings near you. Let them sleep in their maggoty beds. They are not going to get me this innings. Warm beds: warm fullblooded life. (103)

This is Bloom’s version of Stephen’s visible and audible walk along the seashore, connecting him again to the sensory world:

The grainy sand had gone from under his feet. His boots trod again a damp crackling mast, razorshells, squeaking pebbles, that on the unnumbered pebbles beats, wood sieved by the shipworm, lost Armada. (37-8)

And soon they will be brought together, to find comfort from each other, Bloom lending his care to Stephen in Section 3 of the novel.

Any account of Ulysses can give only one small part of the whole.

As Cedric Watts say in his introduction, ‘Anyone who studies Ulysses soon realizes that Joyce’s imaginative intelligence and critical acumen exceed those of virtually all his commentators’. (xxxviii) I have concentrated here on what I see as overarchingly important about the novel, its celebration of life. All its technical innovations, its linguistic brilliance, its magnificent wealth of allusions, its narrative pyrotechnics, its plumbing of the depths and its skimming of the shallows of consciousness – these are in the service of representing life. To return to that modernist question, can there be a material reality underlying the multiple versions of it refracted through multiple consciousnesses? Some modernists answered this with a no, and their work reflects that in textual and linguistic fracture and even dissolution. Joyce, for all that Ulysses is the last word in textual multiplicity, instead answers it with an emphatic yes – in the same way as the novel itself ends.

From Stephen Daedalus’s high-minded reflections as he looks over the sea from the Martello tower early on in the novel, to Bloom’s reclining top to bottom with his wife’s body near its end, the novel turns topsy-turvy anything expected or predicted. It also turns us as readers upside down, and surely we come out of it less judgemental for the experience. Bloom settles into bed top to toe with Molly, recognising ‘the imprint of a human form, male, not his, some crumbs, some flakes of potted meat, recooked, which he removed’. He settles nonetheless happily, head against ‘the plump mellow yellow smellow melons of [Molly’s] rump’, and ponders her infidelity with equanimity:

Equanimity?

As natural as any and every natural act of a nature expressed or understood executed in natured nature by natural creatures in accordance with his, her and their natured natures, of dissimilar similarity. As not as calamitous as a cataclysmic annihilation of the planet in consequence of collision. As less reprehensible than theft, highway robbery, cruelty to children and animals, obtaining money under false pretences, forgery, embezzlement of public money, betrayal of public trust, malingering, mayhem, corruption of minors… (636)

There are other reflections, but all are in the spirit of forgiveness, Leopold Bloom’s strong suit, and the novel’s.

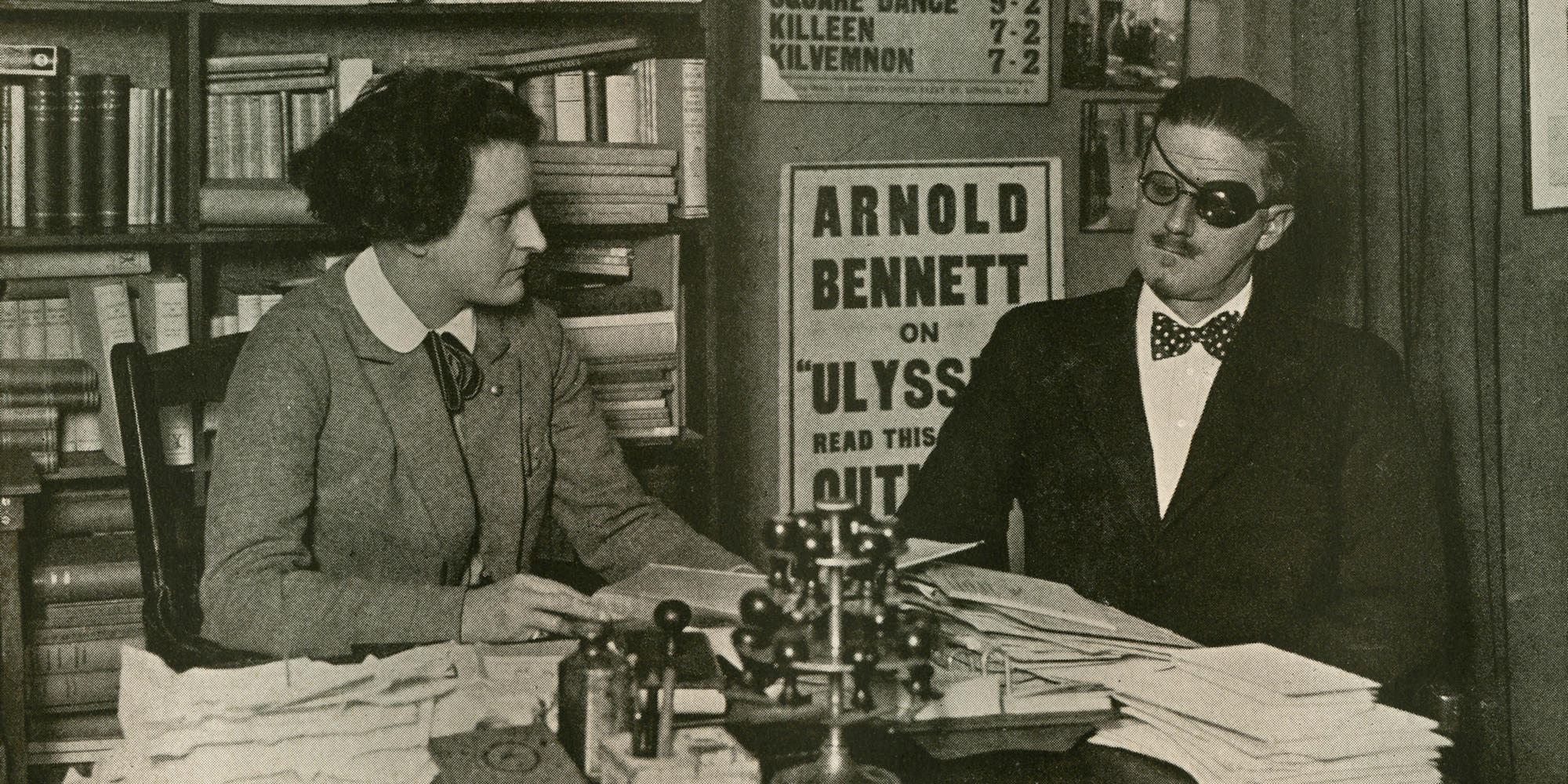

If Joyce is generous with his reach, he is also culturally magnanimous. The BBC has placed the centenary of Ulysses at the centre of its current celebration of Modernism, and this offsets to some extent an emphasis that could be criticised as predominantly Anglophone, even Anglocentric. Joyce is notable in having placed himself within a broader European cultural identity by his self-exile from Ireland and his choosing Trieste, Zurich and Paris as his places of being and writing. Even before that, he was already an outsider to the literary establishment by being born in Ireland; and while Yeats was accommodated by that establishment, Joyce never could have been. Not for nothing is it that Ulysses was published first in Paris, by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Co. When Harriet Weaver, the first great supporter of the novel in its earliest versions, published a second edition via her Egoist Press in Paris, and sent 500 copies to England in 1923, they were seized by His Majesty’s Customs and Excise at Folkestone, and burned.

If Joyce is generous with his reach, he is also culturally magnanimous. The BBC has placed the centenary of Ulysses at the centre of its current celebration of Modernism, and this offsets to some extent an emphasis that could be criticised as predominantly Anglophone, even Anglocentric. Joyce is notable in having placed himself within a broader European cultural identity by his self-exile from Ireland and his choosing Trieste, Zurich and Paris as his places of being and writing. Even before that, he was already an outsider to the literary establishment by being born in Ireland; and while Yeats was accommodated by that establishment, Joyce never could have been. Not for nothing is it that Ulysses was published first in Paris, by Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Co. When Harriet Weaver, the first great supporter of the novel in its earliest versions, published a second edition via her Egoist Press in Paris, and sent 500 copies to England in 1923, they were seized by His Majesty’s Customs and Excise at Folkestone, and burned.

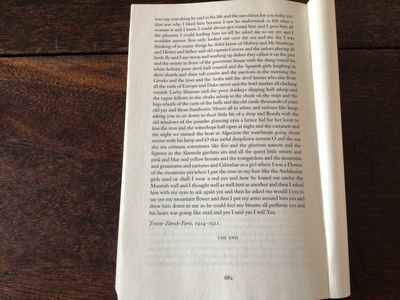

I return finally to the question of Joyce’s writing of the female. To my mind Molly Bloom’s soliloquy remains one of the best pieces of writing of the twentieth century and beyond. Nothing even remotely like it had been written before in English, representing a woman’s sexuality as one part of and alongside all the other elements of her thoughts and feelings. And even though it is 100 years old today, I still have to read any writing to equal it in its imaginative openness, its extraordinary fluidity across time and mood, and its technical brilliance and innovation. And that is not to mention its glorious optimism. To me it matters not a jot that it was written by a man. That man is Joyce, and as we have seen his imagination has a compass that still outstrips us in the 21st century. Male appropriation? Yes! But that is what all writers do, of any gender or none. They imagine. They put themselves into the shoes of others. Some do it well, some badly, but Joyce does it brilliantly. That he gave a woman such a spectacularly powerful voice to end his novel is undoubtedly one of the reasons for those book burnings. Happily it was also a woman, Sylvia Beach, who ensured that there was a book to burn in the first place.

Ulysses is then still the novel to shake our consciousnesses, to cross the borders it was once not allowed to cross, to remind us both of our common humanity and of our differences, and to fly by the nets of ‘nationality, language, religion’[1]:

It is, in short, the most faithful X-ray ever taken of the ordinary human consciousness. … Joyce, including all the ignobilities, makes his bourgeois figures command our sympathy and respect by letting us see in them the throes of the human mind straining always to perpetuate and perfect itself and of the body always labouring and throbbing to throw up some beauty from its darkness.

(Edmund Wilson, reviewing it for The New Republic, July 4th 1922)

One hundred years on, Ulysses remains a novel unlike all others, and one to shed some light in our dark times.

The BBC Modernism season is featured on Radio 3 and Radio 4 and BBC Sounds; all details can be found at www.bbc.co.uk. On Ulysses, I would particularly recommend Archive on Four, Radio 4, January 29th, 20.00: ‘Paris-Zurich-Trieste: Joyce l’European’; the Essay series on Radio 3, 22-45 all this week, with various contributors; and Petroc Trelawny’s Breakfast on Radio 3 every morning this week, 6-30-9 am, celebrating Joyce and the centenary of Ulysses throughout the week via musical links and connections.

The British Library has some interesting material, including a post on Ulysses and Obscenity, www.bl.co.uk.

Modernism Lab is a website run by Yale University and has all sorts of interesting material on Modernism, and on Joyce in particular. The link is www.campuspress.yale.edu.

[1] James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

Main image: Sylvia Beach, publisher of ‘Ulysses’ and James Joyce in Paris. Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo

Images above courtesy of Sally Minogue

Books associated with this article