Under the Tuscan sun with Romeo and Juliet

In praise of serendipity: Stefania Ciocia’s chance encounter with Romeo and Juliet in the Tuscan countryside

The pleasure of revisiting cultural favourites has been one of my coping strategies against the uncertainty of these strange, scary times. Stuck at home, with no immediate prospect of seeing my family in Italy, and still counting my blessings, I find that I have little to no mental energy to be adventurous in my artistic pursuits. I cling to the comfort of old friends – books and films and live performances – which I am sure will repay my attention with the special solace of treading well-known and much-loved paths, with the added pathos that I was last there in less anxious circumstances.

In the past few weeks alone, I have been back to Italy more often than in the twenty-odd years since I left it: I have taken in the fragrance of the Ligurian lemons in Eugenio Montale’s poetry, felt the harshness, and the life-giving power, of the Mediterranean in Giovanni Verga’s I Malavoglia, clung on to the hope against hope in the last line of Eduardo De Filippo’s Napoli milionaria (“Adda passa’ ‘a nuttata”: “this night too shall pass”). I have basked in the innocent energy of a country poised on the brink of modernity, the post-war “Italian miracle”, captured by Vittorio De Sica’s The Gold of Naples and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow, and Mario Monicelli’s Big Deal on Madonna Street. I wish these jewels were all better known outside Italy.

Turning away from my native shores, I have continued to self-medicate with abundant helpings of a slightly different kind of nostalgia, tuning in to the online streaming of performances that I was lucky enough to see live at the theatre. Recent highlights include Inua Ellams’ vibrant Afropolitan The Barber Shop Chronicles at the National Theatre, a groovy Glyndebourne production of Le nozze di Figaro (which I’d first caught on tour here in Canterbury about a decade ago), and the absolute rollercoaster of emotions that is Puccini’s Il Trittico, in its Royal Opera House staging.[1] Yet as I burrow deep into the familiar, I remind myself that there’s a unique joy to be had in serendipitous encounters and discoveries, happiness augmented by magical thinking, by the conviction that the planets must have aligned for a certain book or film or show to have landed into one’s lap.

Last summer I experienced a delicious mingling of these two pleasures – the warmth of reacquaintance and the thrill of the unexpected – with an intensity that floored me. I had been travelling through Tuscany, following an itinerary that I’d uncharacteristically plotted with great care before setting off from the UK. I’d wanted to cram a bit of everything into that visit: the clear seaside of the Maremma, the rolling hills around Siena, before heading north to pay homage to Puccini in his home town of Lucca, and proceed on a whimsical cultural pilgrimage to Volterra in the footsteps of Hema and Kaushik, the protagonists of the narrative triptych at the close of Jhumpa Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth.

My travel companion had been happy to go along with my recommendations: he hadn’t been to Lucca before, and the mysterious Etruscan past of dour Volterra appealed to him. Besides, you can’t really go wrong in Tuscany: dove caschi, caschi bene. You’re bound to end up somewhere good. As it happens, I owe my most enduring memory from that trip to one impromptu contribution to the itinerary made by my partner, who suggested that we should stop en route to see for ourselves “the utopian city” of Pienza.

Perched on a hilltop in the Val d’Orcia, it was the site of a famous experiment of urban redevelopment executed by Barnardo Rossellino in accordance with the symmetrical patterns and ideal proportions propounded by Leon Battista Alberti, the father of Renaissance architecture. The works were carried out under the patronage of the humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who had been born there in 1405 and had become pope Pius II in 1458. The year after his election marked the beginning of the transformation of Corsignano, as the village was then known, into Pienza, thus renamed to celebrate its most illustrious citizen and benefactor. The city of Pius remains to date one of the best-preserved examples of fifteenth-century urban planning. Its luminous cathedral dominates the relatively small main square, but the beauty of the Duomo is no match to the showstopper that is discreetly in store for the visitors of the adjacent Palazzo Piccolomini.

Perched on a hilltop in the Val d’Orcia, it was the site of a famous experiment of urban redevelopment executed by Barnardo Rossellino in accordance with the symmetrical patterns and ideal proportions propounded by Leon Battista Alberti, the father of Renaissance architecture. The works were carried out under the patronage of the humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who had been born there in 1405 and had become pope Pius II in 1458. The year after his election marked the beginning of the transformation of Corsignano, as the village was then known, into Pienza, thus renamed to celebrate its most illustrious citizen and benefactor. The city of Pius remains to date one of the best-preserved examples of fifteenth-century urban planning. Its luminous cathedral dominates the relatively small main square, but the beauty of the Duomo is no match to the showstopper that is discreetly in store for the visitors of the adjacent Palazzo Piccolomini.

The entrance to the building is through a square inner courtyard surrounded by an elegant portico, but I challenge any visitor to head straight indoors before walking into the “back” garden to which this space also leads. It is an exquisite, perfectly proportioned Italian garden, with box hedges and citrus plants in huge terracotta pots; you look around, fit to burst with the harmony of the setting until your gaze turns to an arch that reveals a breathtaking view of the valley. And that’s the coup de grace, a full assault to the senses: you are in a Renaissance painting. Ambushed by such a surfeit of beauty, I burst into tears. It was an instant, the suddenness of the discovery, that made it so affecting. Later on, gorging more fully on the same landscape, from the loggia on the second floor of the building, still felt amazing, a gift from the gods, but not as miraculous as that first, electrifying impression.

The entrance to the building is through a square inner courtyard surrounded by an elegant portico, but I challenge any visitor to head straight indoors before walking into the “back” garden to which this space also leads. It is an exquisite, perfectly proportioned Italian garden, with box hedges and citrus plants in huge terracotta pots; you look around, fit to burst with the harmony of the setting until your gaze turns to an arch that reveals a breathtaking view of the valley. And that’s the coup de grace, a full assault to the senses: you are in a Renaissance painting. Ambushed by such a surfeit of beauty, I burst into tears. It was an instant, the suddenness of the discovery, that made it so affecting. Later on, gorging more fully on the same landscape, from the loggia on the second floor of the building, still felt amazing, a gift from the gods, but not as miraculous as that first, electrifying impression.

The older I get, the easier I well up. I wouldn’t have thought this is uncommon. I have long stopped thinking of myself as a tough cookie, unsentimental, the serious, studious, cerebral girl, the role allotted to me in my extended family when I was growing up. In my mid-forties, I enjoy being overwhelmed by things of beauty. I think I am lucky to feel so strongly, though it does occasionally embarrass me, this crying in public for no apparent reason. So I skulked around in the Piccolomini garden, trying not to be seen by fellow tourists. We were mercifully few on that intemperate summer day, brandishing our mobile phones and audio guides, timing our photographs with the sunny breaks from the rain. I might have just about held it together, had it not been for the music piping through the courtyard, on a loop: the love theme from Nino Rota’s soundtrack to Romeo and Juliet.

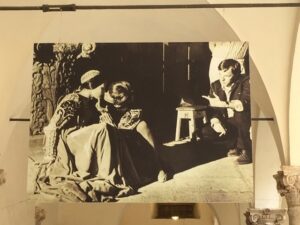

For, you see, Palazzo Piccolomini is cast as the Capulets’ house, while Pienza passes itself off as Verona, in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 cinematic take on Shakespeare’s play. A giant photograph of Olivia Hussey as Juliet had greeted me in the inner courtyard of the building, part of a temporary exhibition about the making of the film, telling me that I had been there before, in my travels on celluloid. After the holiday, I rushed to get a copy of the film to go back to Pienza. I have recently watched it again, for much the same reason, and as a memorial of sorts for the great Italian director, who died a year ago today.

For, you see, Palazzo Piccolomini is cast as the Capulets’ house, while Pienza passes itself off as Verona, in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 cinematic take on Shakespeare’s play. A giant photograph of Olivia Hussey as Juliet had greeted me in the inner courtyard of the building, part of a temporary exhibition about the making of the film, telling me that I had been there before, in my travels on celluloid. After the holiday, I rushed to get a copy of the film to go back to Pienza. I have recently watched it again, for much the same reason, and as a memorial of sorts for the great Italian director, who died a year ago today.

His Romeo and Juliet has aged remarkably well, even if it has been surpassed in popularity by Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 extravagant modern-day reimagining of the star-crossed lovers’ tragic tale. The earlier film broke new ground for Zeffirelli’s bold decision to cast two unknown teenagers in the title roles: Olivia Hussey was only sixteen and Leonard Whiting seventeen when the film was released. Their youth is as dazzling as their beauty, but I disagree with those who see it as giving a topical edge to the story at a time of student protest, political activism and rebellion all over the world. Zeffirelli reclaims the main characters to adolescence, but their transgressions – such as they are – are in the personal rather than the public sphere, their actions fuelled by self-absorbed desire rather than a generational conflict about values, or the more indistinct dissatisfaction with the status quo that is the prerogative of our teenage years.

“Romeo was your first ‘rebel without a cause’”, according to Luhrmann. Not so for Zeffirelli: his Romeo is an innocent, with the impetuosity of youth in his volatile affection for poor Rosaline, in the tender, all-consuming passion for Juliet, in his naïve goodwill towards quarrelsome Tybalt, in the accidental role he plays in the killing of Mercutio, and the instinctive violence he unleashes to avenge him. One would think he hadn’t just witnessed the mortal consequences of sword-fighting, judging from his horrified reaction at his own murder of Tybalt.

Juliet too is a child, schooled by her mother to accept her engagement to Paris as an honour, and petted and teased by the Nurse. The older woman has other, more carnal joys in mind than the prestige of the husband-to-be when she congratulates her charge for her impending nuptials. Her bawdiness highlights the otherworldly purity that Juliet retains throughout her relationship with Romeo: from her concerns about propriety in the balcony scene, to her demure piety during the marriage ceremony, and her immaculate, doe-eyed appearance when she wakes up next to her husband after the wedding night. The thing about Romeo and Juliet is that their constant reaching for one another is both utterly convincing and strangely asexual as if they were playing at being grown-ups, engrossed in a game – a dress rehearsal for an imperfect life they will never get to live – with the sincerity of inexperience.

Juliet too is a child, schooled by her mother to accept her engagement to Paris as an honour, and petted and teased by the Nurse. The older woman has other, more carnal joys in mind than the prestige of the husband-to-be when she congratulates her charge for her impending nuptials. Her bawdiness highlights the otherworldly purity that Juliet retains throughout her relationship with Romeo: from her concerns about propriety in the balcony scene, to her demure piety during the marriage ceremony, and her immaculate, doe-eyed appearance when she wakes up next to her husband after the wedding night. The thing about Romeo and Juliet is that their constant reaching for one another is both utterly convincing and strangely asexual as if they were playing at being grown-ups, engrossed in a game – a dress rehearsal for an imperfect life they will never get to live – with the sincerity of inexperience.

When dawn breaks on their marital bed, and the camera pans on their naked bodies, we are treated to an exquisite sight, white sheets carefully draped as if sculpted in marble, the recumbent forms impossibly good-looking and composed. It is a celebration of beauty so idealized that it looks almost incorporeal, and chaste, despite the amount of flesh on display. The two newlyweds are a picture of edenic grace, their mutual attraction an aesthetic inevitability more than the by-product of raging hormones. The knowledge that this is the last time they’ll see each other alive is heartbreaking.

In no other Shakespearean play is there such an abrupt change from comedic possibilities to tragic doom. Mercutio’s death is like the flicking of a switch: from courtly revels and love at first sight, from the trusting expectancy of youth and the delight of secret rendezvous, we plunge headlong into a nightmare.[2] Romeo and Juliet respond to this about-turn as the children that they are: they bawl their eyes out. Theirs are not silent tears, but full-blown, dramatic tantrums, wringing of hands and rolling on the floor included, a literal rendition of the “Blubbering and weeping, weeping and blubbering” with which the Nurse describes Juliet’s distress.

And if Friar Laurence’s stern reprimand of Romeo is a call for the disconsolate lad to pull himself together (the “There are thou happy” speech a proper telling off), the Capulets’ response to their daughter’s anguished refusal to marry Paris is shocking in its psychological violence. Added to the coercive behaviour of Juliet’s parents, the Nurse’s pragmatic advice that the girl may well find happiness in her second marriage is the final betrayal perpetrated by one generation against another. It will find an echo in the Friar’s repeated, cowardly “I dare no longer stay”, when he abandons Juliet to discover that Romeo lies dead next to her in the vault. Against their elders’ dereliction of duty, the young are all alone.

And, in a nutshell, this is the fundamental difference between Zeffirelli’s and Luhrmann’s vision. One expects no better of the gaudy, seedy, morally-decadent Verona beach, with its gun-toting, drug-taking, hedonist characters. In that highly performative world, where even Miriam Margolyes’s Nurse is a wallflower against her riotous, colourful surroundings, the protagonists’ innocence is relative, and comes pre-packaged in their fancy-dress costumes: Claire Danes’ Juliet as an angel, Leonardo DiCaprio’s Romeo as a knight in shining armour. Capulet’s rage towards his daughter is in keeping with his mobster persona, as is the parental void left unfilled by Lady Capulet: her perfunctory administering of maternal advice while getting trussed up as Cleopatra in the opening scene with Juliet tells us everything we need to know about the domestic priorities in this household.

But in Zeffirelli’s traditional staging, under the Tuscan sun, against glorious Renaissance architecture, with sumptuous costumes, and plangent madrigals, the death of the beautiful innocent young couple is the ultimate irruption of chaos into order. Of course, Mercutio, played with dark energy by John McEnery, knew of the horror lurking beneath the surface of things all along. After the intermission (remember those?), Zeffirelli shows us McEnery seeking shelter from the heat, his face shrouded by a handkerchief and turned into a grotesque by his babbling. It’s an arresting image, a foreshadowing of ingenious simplicity from a director better known for the lavishness of his productions. Compared to Luhrmann’s, Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet is positively understated. It is well-worth rediscovering though. Especially if, like me, you enjoy racking up frequent flier’s miles with your armchair travelling.

Dr Stefania Ciocia is a Reader in Modern and Contemporary Literature at Canterbury Christ Church University. You can find her on Twitter as Gained in Translation @StefaniaCiocia.

Main image: Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting in Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet 1968

AF archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Blog images courtesy of Stefania Ciocia

[1] Allow me a shout out for Giorgetta’s ‘È ben altro il mio sogno’ as being on a par with Puccini’s most famous arias. It’s a distillation of yearning into music, a visceral expression of homesickness.

[2] After Romeo is exiled to Mantua, the narrative hurtles towards its conclusion: no killing of Paris, no mucking about with the apothecary, the latter perhaps a cut too much. Does Romeo always carry a vial of poison in his doublet?

Books associated with this article

Romeo and Juliet (Collector’s Edition)

William Shakespeare