Influential English writer: Virginia Woolf

Sally Minogue writes in praise of the influential English writer.

Virginia Woolf was born in 1882 into a highly literary family. Her first novel was published in 1915 and her last in 1941, in an intensive writing career which included reviews, letters, essays and biographies as well as the novels for which she is famed. She and her husband Leonard also founded the influential Hogarth Press. Her life and her writing were dogged by bouts of severe mental illness to which she succumbed finally, taking her own life in 1941.

In a recent edition of the quiz show ‘Pointless’, the questions were based on the general public’s knowledge of Virginia Woolf’s writing. As the show’s presenter remarked, that knowledge was surprisingly good, with only five pointless answers in relation to her large body of works. Woolf herself would have been supremely indifferent to that fact; the great British public did not loom large on her consciousness. But she would have been deeply pleased that her work had lived on, and had influenced the art of writing. In her fiction she went deep into the heart of human consciousness, experimenting boldly with language and narrative. In 1908, when she was writing her very first novel, The Voyage Out, she could look forward excitedly to all she might do as a novelist, ‘how I shall re-form the novel and capture multitudes of things at the present fugitive, enclose the whole and shape infinite strange shapes’. By the end of her life in 1941, she could justly claim to have done that.

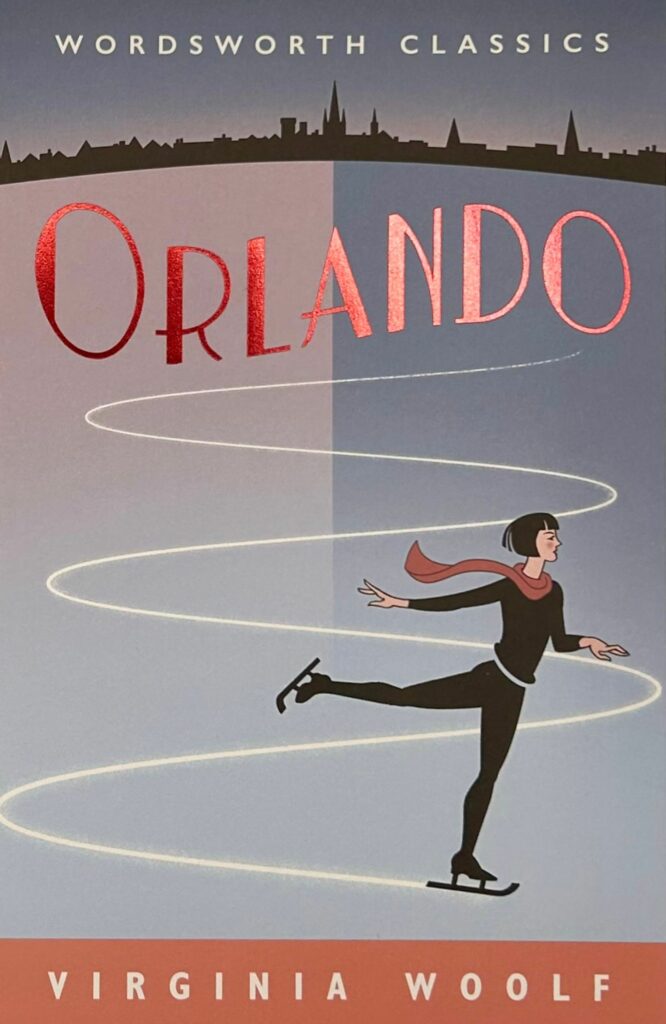

There are some key novels. In Mrs Dalloway, Woolf takes a day in a society woman’s life but builds out of it her mental history and her innermost fears and desires, which are mirrored in the fractured mind of Septimus Smith, a World War One survivor. (Michael Cunningham’s The Hours, and the subsequent film, riffs brilliantly on this novel, its making and its themes.) In To the Lighthouse, perhaps her best-known and best-regarded novel, she asks what fiction is even as she writes it. She always asks what reality is too, offering us multiple visions of the world. The Waves carries experimentation further, deeper into pure consciousness. Orlando has as its hero/heroine a man who turns into a woman, migrating through history. It, too, has inspired a twentieth-century film, with Tilda Swinton as the protagonist.

Woolf’s essays have more recently been regarded as deeply influential. A Room of One’s Own has become a central feminist text. Her shorter pieces on writing, literature, and the imagination, and also on apparently more everyday issues such as ‘being ill’, still speak to us. She had a lighter side too: Flush tells the story of Elizabeth Barrett Brownings’ spaniel – in the dog’s own words!

Woolf has her faults and her detractors. Social and intellectual snobbery mars her work, though it is more evident in her less guarded letters and diaries. But her revelations about the human mind and its extraordinary workings pierce deep into areas untouched by these temporary and temporal concerns. There’s no doubt that her unusual understanding of consciousness, and her ability to represent it in language, were informed by her own bouts of mental illness. These crippling attacks punctuated her life, and they led finally to her suicide by drowning in March 1941. She had just passed her 59th birthday and just finished Between the Acts. As often at the end of the spell of intense creative activity involved in completing a novel, she felt her illness approaching again, and couldn’t face the struggle with it that she had so many times before courageously undertaken.

We should salute her courage today for sustaining that long struggle, and for producing a body of work which is like no other.

Sally Minogue is a retired academic who has published mainly on nineteenth and twentieth-century fiction and poetry, including Charlotte Brontë, Thomas Hardy, Ivor Gurney, Virginia Woolf and Alan Sillitoe. She has a long-standing love of poetry, particularly as it intersects with a common language, and is currently working with a colleague on a book about World War One poetry and its aftermath. She was for several years the Membership Secretary of the Ivor Gurney Society.

Books associated with this article

The Waves

Virginia Woolf

To the Lighthouse

Virginia Woolf

Mrs Dalloway

Virginia Woolf

Orlando

Virginia Woolf