W.B. Yeats and the Nobel Prize

This week marks the centenary of W. B. Yeats being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature – the first Irishman to be granted that honour. Sally Minogue looks at Yeats’s achievement and suggests some of his poems to enjoy.

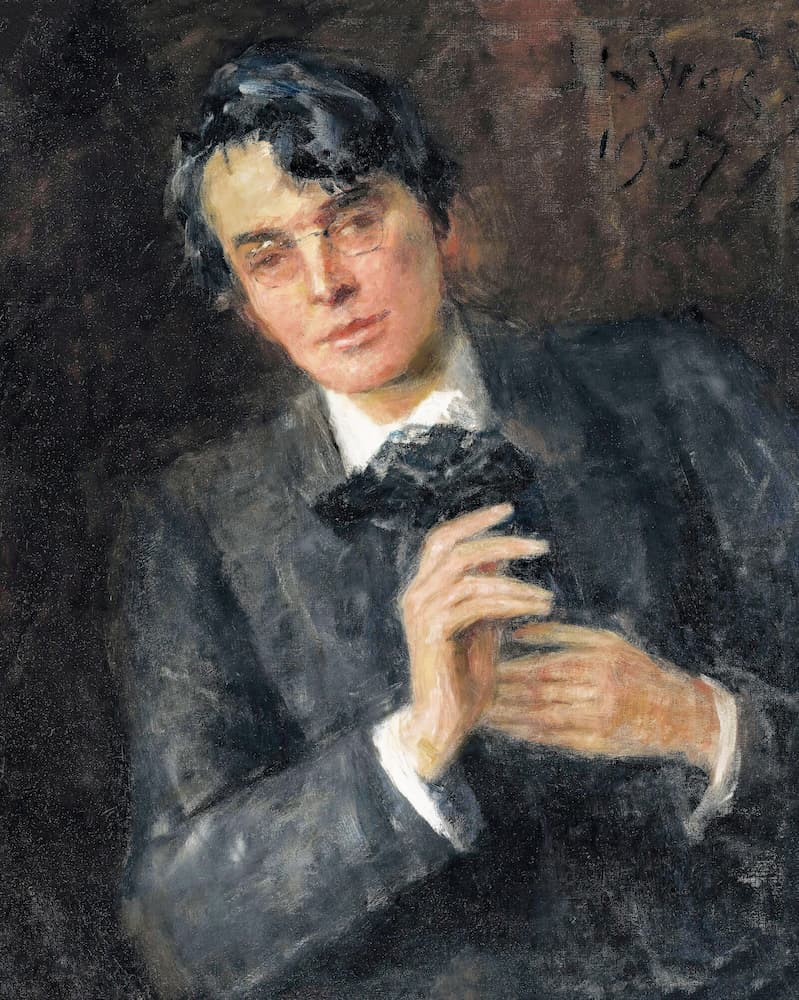

Portrait of Yeats by his father.

W.B. Yeats was 58 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature – a good age, one might think, the right sort of age for such a prize. But much of what is usually regarded as his best work was still to be written: ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, ‘Leda and the Swan’, the mighty ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, the self-reflective ‘Among Schoolchildren’. And those are just from one collection, that of 1928, The Tower, which followed on from his award in 1923. There were five more collections to be written and published after that.

I have been dwelling on poets’ ages lately as I have been writing the Introductions to the two volumes of Dylan Thomas’s work to be published by Wordsworth early next year. If Yeats at 58 still had a third of his poetic life to live when he received the Nobel Prize, poor old Dylan Thomas was dead by the age of 39, still well below the Nobel radar. The Prize’s youngest recipient remains Rudyard Kipling who was named Nobel laureate in 1907 at the age of 41. Age does matter in the Swedish Academy, but only within a broad spectrum, the reason being that it’s unlikely that a writer will have built up a sufficiently substantial body of work before a certain age. As it happens, Thomas is an excellent counter-example to that, since he began writing (really rather good poems) by the age of 16, and already had a significant oeuvre across several genres of writing when he died.

The Swedish Academy’s imprimatur isn’t all about achieved work, it is also about spotting a good bet. Yeats, though 58, certainly turned out to be that. Possibly Kipling did also; he it was who wrote some of the memorial lines forever associated with the First World War, derived from Biblical sources but honed by him: ‘Their Name Liveth Forever More’ on the Stones of Remembrance in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries, ‘The Glorious Dead’ on the Cenotaph, and ‘Known Unto God’ on the graves of the bodies of unidentified combatants. All a form of poetry which both answered to and helped to form the public mood.

One of the effects of the Nobel Prize is that it attracts the public’s attention. Readers turn towards the anointed writer as sunflowers turn to the sun. Perhaps too, receiving the Prize imbues the writer with confidence so that s/he can assuage that needy gaze – though it has to be said that it also robs the recipient of time, perhaps the thing most important to a writer. Everyone wants a piece of a Nobel winner. Yeats had done good work, but he was also a good bet – aided, as it turned out, by his living a reasonably long life. He was also poised at the centre of a hugely significant cultural and political moment. The Swedish Academy has always denied any political intent, yet it remains remarkably canny about cultural politics. To me, that is one of its strengths and interests. The number of times when the winner is announced and everyone says ‘Who?’ is a marker of this, balancing out the number of times when the winner is announced and everyone says ‘Yes!’ The Academy somehow achieves a balance between the well known and well recognised and the little known and little recognized, and makes us feel that both are equally worthy of the Prize. It is usually in the less well known category that cultural politics comes into play. The 2023 winner Jon Fosse writes in the less common form of written Norwegian, Nynorsk, so he is in a linguistic minority, and Norway itself may be seen as in a geographical and cultural minority, though in fact there have been three previous Norwegian winners of the Literature Prize.

Mural of Maud Gonne MacBride, Sligo Town

Yeats was the first Irish recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature. He was born (in Dublin) into a Protestant family, and educated in England, so was part of the establishment which had kept a predominantly Catholic Ireland subjugated. However, through his writing and his cultural politics he became a key figure in the Irish cultural revival, which was in itself an expressive arm of the revolutionary struggle for Irish independence. Maud Gonne, whom he loved, was in the thick of that movement. In his poetry, Yeats wrote of that struggle, in a way that understood the complexity of its violent politics but never endorsed them. After the Easter Rising of 1916, the Irish War of Independence (against British forces) ended with the partition of Ireland under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, and though it was signed by Michael Collins as a representative of the Irish Republic, it was seen by those seeking full independence for Ireland as a betrayal. Under its terms, the Irish Free State was established in the South, with the six Northern Counties, under partition, remaining fully British (as they still remain). The Irish Free State had self-government but was, crucially, still a dominion of Britain. In 1922 Yeats became a Senator of the Upper House of its main Parliament, the Dail, thus taking the conservative, pro-Treaty side in what became a bloody civil war between opposing wings of the revolutionary movement. Yeats had by that time already been nominated several years running for the Nobel Prize. However, in 1923 he was nominated by the full membership of the Nobel Committee for Literature. Perhaps not surprising then that he won the Prize. Yeats’s nationality was specifically mentioned in his Nobel citation: ‘for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation’. That nation was Ireland. Whole nation of course it wasn’t, and still isn’t. The Nobel Prize being awarded at that precise moment lauded the poet for what was certainly a magnificent body of work already, implicitly recognized his importance in the Irish cultural revival which was a part of the Independence movement, but also by its timing endorsed his distancing himself somewhat from that movement. At the same time, the establishment of the Irish Free State was a large step towards the inevitable independence of Ireland/Eire and in being party to it, the Britain bowed to the eventual loss of a significant part of its Union. Thus Yeats’s Nobel Prize landed in his and Ireland’s lap at a political crux, whose unresolved complications and tensions are still evident today.

25 years earlier, Rudyard Kipling had received the Prize for work that undoubtedly supported colonial values, however he might have disrupted and ironised them. In 1907, irony wouldn’t have played much part in the way his work was seen, even though his extraordinary novel Kim is full of it, as it is full of questioning of Empire as well as consolidating it. The Academy’s citation for Kipling desired ‘to pay homage to the literature of England, so rich in manifold glories’. It singled out Kipling’s narrative art for praise, narratives that are set firmly in the midst of Empire. It’s remarkable that 25 years later the poet of a nation that had once been part of that Empire was being cited by the Academy for giving ‘expression to the spirit’ of that ‘whole nation’.

Coincidentally Kipling and Yeats were born in the same year, 1865, which reminds us that they were firmly Victorian figures, but Yeats’s involvement in the cultural politics of the Irish struggle for independence undoubtedly turned his work in a different direction, as did his later disengagement with it as his poetry became more and more clearly Modernist. Where Yeats’s writing changed and developed, making him a notably modern poetic voice of the first half of the twentieth century, Kipling remained stuck in his imperial identity.

In a previous blog about Yeats in 2021 I have talked about a number of his best-known poems, including those associated with Irish politics such as ‘Easter 1916’, but his is such a wide-ranging and richly diverse body of work that there is really something there for everyone. He was a master of the short lyric poem, a form that runs through his oeuvre from beginning to end. Here is the first of the two stanzas that form one of his earliest poems, from his first collection Crossways (1889), ‘The Falling of the Leaves’:

Autumn is over the long leaves that love us,

And over the mice in the barley sheaves;

Yellow the leaves of the rowan above us,

And yellow the wild wet strawberry leaves.

Plaque at 82 Merrion Square, Dublin

As I look out of the window on to a wet Autumn garden, those lines could be describing what I see; their voice is direct and personal, their images timeless, their poetics assured. The poet was 25. A later poem, ‘All Things Can Tempt Me’ is a poem about poetry, about his own craft. Dylan Thomas too writes several poems in this vein, and a poet making poetry about their own practice of poetry is always revealing. Yeats’s poem dates from 1910, his fifth collection, and he is also reflecting on the elements in his life that pull him away from his central task of poetry:

All things can tempt me from this craft of verse:

One time it was a woman’s face, or worse –

The seeming needs of my fool-driven land …

The woman was Maud Gonne, Ireland his ‘fool-driven land’. But he continues:

Now nothing but comes readier to the hand

Than this accustomed toil.

Poetry remained the one constant.

In the collection The Tower (1928), his first post-Nobel collection, which coincides with his final year serving as a Senator, there is a marked change of poetic tone. Yeats is now 63, and there is a preoccupation with growing old and at the same time an opposing fascination with the immortality of art. ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ (1927) which seemed to me when I was younger to be all about the eternals of beauty, now strikes me as full of anguish about aging. ‘That is no country for old men’, it begins, and later continues, ‘An aged man is but a paltry thing, A tattered coat upon a stick’. True, against these more-than-intimations of mortality ‘soul’ can ‘clap its hands and sing’. ‘The Tower’ (1926) likewise begins

What shall I do with this absurdity –

O heart, O troubled heart – this caricature,

Decrepit age that has been tied to me

As to a dog’s tail?

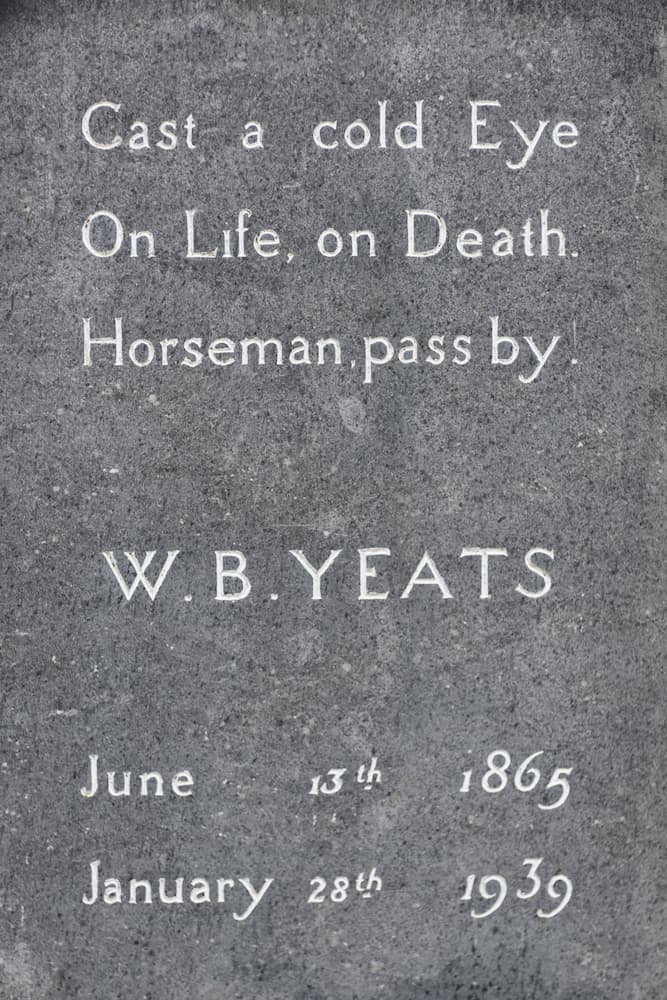

Yeats’ tomb, Drumcliff, County Sligo

But the rest of the poem is a profound yet conversational reflection on a whole life, from boyhood under Ben Bulben to the characteristically distanced tones of ‘It is time that I wrote my will’ in the third section of the poem. Yet, as he has announced at the start, whatever the depredations of age, ‘Never had I more / Excited, passionate, fantastical/ Imagination’.

Here in the late 1920s Yeats seems to be willing a sort of peace with himself, as well as taking on an oracular quality in the voice. Last Poems (1936-39) takes that poetic voice to its conclusion. The personal, autobiographical, reflective voice of ‘The Tower’ and ‘Among Schoolchildren’ has all but disappeared. But one poem in this final collection that I particularly love goes back to that voice, combining regret and gladness. ‘The Municipal Gallery Revisited’ takes as a brilliant vehicle the poet’s return to the Dublin Municipal Gallery to look at the many portraits of those who had figured in the history of Ireland. It gives him the opportunity to reflect upon them, on himself, and on the history of Ireland and its future. In a public lecture given when he was writing the poem, Yeats said:

For a long time I have not visited the Municipal Gallery. I went there a week ago and I was restored to my friends. I sat down, after a few minutes, overwhelmed with emotion. There were pictures painted by men, now dead, who were once my intimate friends. There were portraits of my fellow-workers … Lady Gregory … John Synge … there were portraits of our statesmen; the events of the last thirty years in fine pictures; Ireland not as she is displayed in guide book or history, but the glory of her passions’. The poem is both personal and public. As Yeats does in some of his best political poems, he names names, but here to trace a complex national history, through the frame of the portrait.

The year was 1937 – the year that Ireland gained full constitutional independence from Britain. The Nobel had placed a good bet: here indeed is a poem that ‘gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation’. Yet it is also one that ends personally:

Think where man’s glory most begins and ends,

And say my glory was, I had such friends.

Yeats died two years later. This year we doff a cap to him as we celebrate the centenary of his Nobel Prize; but the real prize is the poetry.

My previous blog on the Nobel Prize for Literature can be found here

Main image: Thoor Ballylee, former home of W. B. Yeats. Credit: Vincent MacNamara / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: A portrait of Yeats by his father, John Butler Yeats. Credit: De Luan / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Mural of Maud Gonne MacBride, Sligo Town, County Sligo. Credit: Piere Bonbon / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Plaque at 82 Merrion Square, Dublin, Co Dublin, Ireland Credit: Design Pics Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Yeats’ tomb, Drumcliff, County Sligo. Credit: Mauritius Images GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on Yeats’ life and work, visit: Yeats Society Sligo | The Official Yeats Website

Our edition is here: https://wordsworth-editions.com/book/collected-poems-of-w-b-yeats/

Books associated with this article