Wells in Free Flight

Laurence Davies looks at H.G. Wells fascination with flight and its depiction in contemporary fiction.

Starting with his early fantasy The Wonderful Visit (1895), which begins with a bright angel from the Land of Dreams soaring over an English landscape, Wells’s fascination with flight permeates his work. That fascination was still strong in 1933, when he published The Shape of Things to Come, where a ‘Dictatorship of the Air’ does away with nationalism and religion in the name of universal harmony. In 1936 Things to Come, the film adaptation of his book shows a world rescued from plague and warfare by ‘Wings Over the World’, a brotherhood of engineers and mechanics who have been biding their time in the deserts of Iraq.

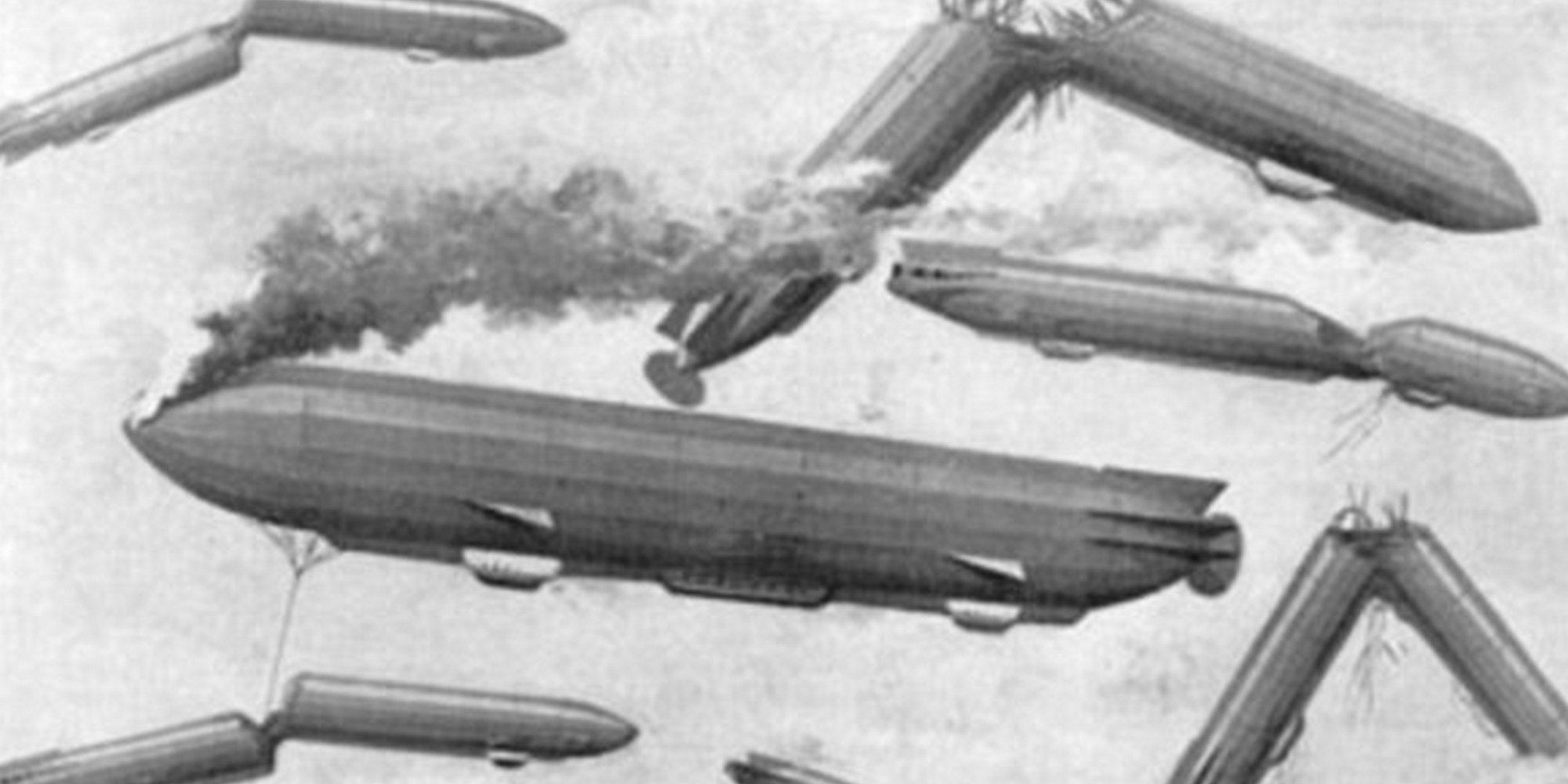

Wells cherished these visions of a planet cleansed and rationalised. Not everyone might agree – his choice of Basic English as the world language, for instance, manages to be both arrogant and bland – but in book and film alike, for him, the skill and no-nonsense experience of the aviators is a force for good. Yet in The War in the Air (1908), as the airforces of rival empires trample on every form of civilisation, the opposite is the case.

This ambivalent view of taking to the skies did not start with Wells. In Book III of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, the savants of the flying island of Laputa have no qualms about dropping rocks on unruly subjects or even using the island’s weight to crush them. Jules Verne wrote two novels about Robur, a brilliant designer and pilot of heavier-than-air flying machines. In the first (1886), he is almost benign in his campaign for a future union of nations. Eight years later, in Maître du monde, Robur comes back as a would-be dictator, the inventor of L’épouvante (the terrible), a machine built to wreak havoc on land, at sea, and in the air. Meanwhile, in Britain, E. Douglas Fawcett’s Hartmann the Anarchist (1892) the City of London goes the way of Babylon. Only a plaintive note from Hartmann’s mother stops him from razing the entire metropolis. On the other hand, Sir Julius Vogel’s future history, Anno Domini 2000; or, Woman’s Destiny (1886) presents the ‘air-cruiser’ as a benefit to civilisation in general and the advancement of women in particular.

Few of these authors give much sense of the exhilaration of flying. One exception is Rudyard Kipling’s story ‘With the Night Mail’ (1905), presented as a magazine article of the future which describes a dirigible voyage from London to Quebec City; the writer, a journalist, describes the beauty of a hospital ship flying up to meet the dawn and the drama of a storm at high altitude

The other exception is Wells. When the Sleeper Wakes (1899) is less familiar than the other ‘scientific romances’, but deserves a bigger audience for its vivid renderings of future shock and puzzlement, not least when the puzzles are seen from on high. The strangeness comes first, and explanations later. On his first flight, Graham (the Sleeper) moves from alarm to elation.

For a second or so he could not lift his eyes. Some hundred feet or sheerer below him was one of the big wind-vanes of southwest London, and beyond it, the southernmost flying stage crowded with little black dots. These things seemed to be falling away from him. For a second he had an impulse to pursue the earth. He set his teeth, he lifted his eyes by a muscular effort, and the moment of panic passed.

He soon finds that aerial land and seascapes have a beauty of their own:

They seemed to leap the Solent in a moment, and in a few seconds the Isle of Wight was running past, and then beneath him spread a wider and wider extent of sea, here purple with the shadow of a cloud, here grey, here a burnished mirror, and here a spread of cloudy greenish blue.

Towards the end of his initiation, he edges forward from the passenger seat to the cockpit. He says to the pilot, who is sworn to professional secrecy:

‘I want to do it myself. Do it myself if I smash for it! No!. I will. See. […] I mean to fly of my own accord if I smash at the end of it. I will have something to pay for my sleep’.

Within a few minutes, he is looping the loop and nose-diving. You could never do that in a balloon.

Wells’s ‘romance’ is more dystopian than utopian, and Ostrog, the ‘Boss’ of Britain, flies in Senegalese troops to subjugate rebellious London, but the once hapless and dejected Sleeper has found his calling. Just as Arthur Kipps finds his happiness in family life and a bookshop, and Mr Polly at a riverside inn, Graham is set free as an exultant aeronaut. The remainder of his life is short but sweet.

Laurence Davies, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Glasgow.