‘The great floodgates of the wonder-world swung open’

Sally Minogue examines the ‘wonder-world’ of Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick.

‘Call me Ishmael’: is there a more famous opening sentence in fiction? People who have never read Moby Dick, people who have never read the Bible, and don’t know who Ishmael is in either text, may still recognize and even in some way understand that resounding sentence, the more memorable for being so succinct. And for all their ancient point of reference, those three short words announce the arrival of a strikingly modern voice. The vocative form creates an immediate intimacy with the reader, while at the same time something compelling underlies it. And so as readers we are drawn almost helplessly into the first page of a narrative which will ebb and flow about us like the great ocean itself. For though the novel begins on dry land, it is always heading for the sea. As the narrator Ishmael confides, ‘Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul … then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can’. He further avers that, ‘If they but knew it, almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feelings towards the ocean as me’.

If we are inclined to disagree in a literal way with this supposed universal attraction, we quickly learn that here the ocean is more than landscape or geography, more even than a great and unruly natural element; it is equivalent to those forces that lie beyond the knowable and comprehensible. The theme of the novel is that as humans we are both impelled towards those forces and fearful of them. Those of us who may with some gusto avoid going down to the sea in ships may still, in the words of Psalm 107, wish to see ‘the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep’. I say this as an atheist, taking that idea, as Melville himself does, beyond the confines of a particular religion to a larger profound notion of the ungraspable in nature and in ourselves. It is one of the strokes of genius, in a novel with many such strokes, that Melville makes the sea he takes us wandering across both terrifyingly actual and a perfect metaphor for the ineffable (that which can’t be expressed in words). Here again we see the modernity of a novel which, though published in 1851, looks ahead to many of the concerns of twentieth-century modernism. Moby Dick is on the one hand an adventurous whaling story, a sea tale, but on the other an attempt to create a narrative large, multifarious and flexible enough to capture a mystery that is constantly eluding it, just as the great white whale eludes Captain Ahab.

If we are inclined to disagree in a literal way with this supposed universal attraction, we quickly learn that here the ocean is more than landscape or geography, more even than a great and unruly natural element; it is equivalent to those forces that lie beyond the knowable and comprehensible. The theme of the novel is that as humans we are both impelled towards those forces and fearful of them. Those of us who may with some gusto avoid going down to the sea in ships may still, in the words of Psalm 107, wish to see ‘the works of the Lord, and his wonders in the deep’. I say this as an atheist, taking that idea, as Melville himself does, beyond the confines of a particular religion to a larger profound notion of the ungraspable in nature and in ourselves. It is one of the strokes of genius, in a novel with many such strokes, that Melville makes the sea he takes us wandering across both terrifyingly actual and a perfect metaphor for the ineffable (that which can’t be expressed in words). Here again we see the modernity of a novel which, though published in 1851, looks ahead to many of the concerns of twentieth-century modernism. Moby Dick is on the one hand an adventurous whaling story, a sea tale, but on the other an attempt to create a narrative large, multifarious and flexible enough to capture a mystery that is constantly eluding it, just as the great white whale eludes Captain Ahab.

But let’s go back to the beginning again. The Ishmael invoked in that first sentence is the outcast in the opening book of the Bible, Genesis. He is the first son of Abraham, but his mother is not Abraham’s wife Sarah, who is infertile, but Sarah’s handmaiden Hagar. An angel appears to Hagar when she is pregnant and commands, ‘You shall call him Ishmael’. As a result of tensions between Sarah and Hagar, Ishmael is cast out into the desert, where God saves him with the gift of water. We need only these bare outlines to see why Melville begins the novel as he does – our ‘hero’ and narrator of his own story doesn’t fit in the normal social world, he is saved from that by going to sea (and later he is saved from drowning in the salvational sea, in a secular reverse of the Biblical version). But instead of a divine voice we have the voice of Ishmael himself, and here bidding the reader ‘Call me Ishmael’ in a contingent rather than a commanding way which seems to allow the reader some speculative room. Everything at the start of the novel is on deliberately human, person-to-person terms. This is fitting for one of the first great American novels, written at a time when the nature of democracy itself was being theorized and legislated for, with slavery at the heart of that debate. An attempt to reconcile the South-North divide between slave-owning states and those which disavowed slavery was enacted in the Compromise of 1850, just as Melville was writing his novel (a compromise that failed when the issue came to a head in the Civil War of the 1860s).

The novel is clearly informed by its political moment, and its modes of representation place it clearly on the side of the abolitionists. But I don’t want us to see the novel in those simple terms, and I am sure that Melville didn’t either, since it is written in such a way as to refuse any singularity or polarization of vision. Rather it reveals to us a many-layered world, but one united in the rough democracy of the sea-going community:

The novel is clearly informed by its political moment, and its modes of representation place it clearly on the side of the abolitionists. But I don’t want us to see the novel in those simple terms, and I am sure that Melville didn’t either, since it is written in such a way as to refuse any singularity or polarization of vision. Rather it reveals to us a many-layered world, but one united in the rough democracy of the sea-going community:

Now when I go to sea, I go to sea as a simple sailor, right before the mast … True, they order me about some, and make me jump from spar to spar, like a grasshopper in a May meadow. And at first this sort of thing is unpleasant enough. It touches one’s sense of honor, particularly if you come of an old-established family of the land … And more than all, if just previous to putting your hand in the tar-pot, you have been lording it as a country schoolmaster … The transition is a keen one, I assure you, from a schoolmaster to a sailor … But even this wears off in time.

What of it, if some old hunks of a sea-captain orders me to get a broom and sweep down the decks? What does that indignity amount to, weighed, I mean, in the scales of the New Testament? … Who ain’t a slave? Tell me that.

We see this egalitarian principle played out in close-up in the first chapters, as the all-American Ishmael and his almost-opposite, the exotic and aristocratic Polynesian Queegqueg, give us a rapid demonstration of the power of brotherly love and the importance of tolerance. (Already my words seem mealy-mouthed, since none of this is presented as a moral lesson, but it is difficult to explicate it otherwise when reduced to quotations and summaries.) In the first few chapters we see Ishmael, a white Christian, ending up sharing his bed with the ‘the harpooner, the infernal head-peddler’, Queegqueg. Several pages are devoted to the description of Queegqueg as seen by a semi-naked Ishmael from the bed they are about to share. Although he is termed a wild cannibal (something he doesn’t deny), an abominable savage, a heathen and a purple rascal (that adjective referring to the tattooes that cover his body), the careful and curious-eyed account given of him undermines any reductive presupposition. For even while Ishmael is articulating such presuppositions he is fascinated as he watches the man’s rituals, and we can feel his mind changing. The chapter ends thus:

‘You gettee in,’ [Queegqueg] added, motioning to me with his tomahawk, and throwing the clothes to one side. He really did this in not only a civil but a kind and charitable way. I stood looking at him a moment. For all his tattooings he was on the whole a clean, comely looking cannibal. What’s all this fuss I have been making about, thought I to myself – the man’s a human being just as I am; he has just as much reason to fear me, as I have to be afraid of him. Better sleep with a sober cannibal than a drunken Christian.

And there we have it. The frame of the whole novel is created in that bed. On the next night, after both have attended independently the local Whalemen’s Chapel, where the text of the sermon is, naturally, Jonah and the whale, Ishmael and Queegqueg keep silent company in a downstairs room at the Spouter-Inn. In a classic moment of romantic epiphany, Ishmael ‘felt a melting in me. No more my maddened hand and splintered heart were turned against the wolfish world. This soothing savage had redeemed it.’ The evening ends with Ishmael taking part in his bedfellow’s pagan rituals (matching the earlier shared Christian rituals), followed by a companionable night under the covers:

And there we have it. The frame of the whole novel is created in that bed. On the next night, after both have attended independently the local Whalemen’s Chapel, where the text of the sermon is, naturally, Jonah and the whale, Ishmael and Queegqueg keep silent company in a downstairs room at the Spouter-Inn. In a classic moment of romantic epiphany, Ishmael ‘felt a melting in me. No more my maddened hand and splintered heart were turned against the wolfish world. This soothing savage had redeemed it.’ The evening ends with Ishmael taking part in his bedfellow’s pagan rituals (matching the earlier shared Christian rituals), followed by a companionable night under the covers:

How it is I know not; but there is no place like a bed for confidential disclosures between friends. Man and wife, they say, there open the very bottom of their souls to each other; and some old couples often lie and chat over old times till nearly morning. Thus, then, in our hearts’ honeymoon, lay I and Queegqueg – a cosy, loving pair.

There has been much critical play with these passages to support a queer reading of the novel, which I’ll briefly touch on at the end of the blog. Here, first, I want to consider the novel in the most open way possible, in keeping with what is a notably open, multivocal, digressive and possibly transgressive text.

For though Moby Dick is, as its eponymous title suggests, in that sense monolithic, with a narrative that takes the form of a monomaniacal quest for a single object – to find and kill the whale – that is constantly undermined by the narrative form itself. Ishmael may be the narrator, but his voice is regularly displaced, first by Queegqueg telling of his origins, then by Father Mapple preaching on Jonah, then by the voice of Elijah foretelling doom to any who sail on the Pequod, then the quasi-factual chapter on ‘Cetology’, enumerating the many iterations of the species whale. In a similar way, chapters of dialogue are interspersed with omniscient objective descriptions, and notions of fixed character are repeatedly questioned (as in the overturning at the very start of Ishmael’s understanding of who and what Queegqueg is). The most notable example of this is the way in which the central character Captain Ahab is brought before us. He is foreshadowed by rumour and counter-rumour before he ever appears. And when he does appear the vision is more frightful than that yet conjured, and at the same time tragic and noble in its aspect:

Reality outran apprehension: Captain Ahab stood on the quarter-deck. …

He looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them. … His whole high, broad form, seemed made of solid bronze, and shaped in an unalterable mode, like Cellini’s cast Perseus. Threading its way out from among his gray hairs, and continuing right down one side of his tawny scorched face and neck, till it disappeared in his clothing, you saw a slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish. It resembled that perpendicular seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it, and without wrenching a single twig, peels and grooves out the bark from top to bottom, ere running off into the soil, leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded.

Apart from this being our first sighting of the vaunted Ahab, it is a superb example of Melville’s descriptive powers, a major element in the readerly pleasure of the novel. We see Ahab through Ishmael’s terrified eyes, but we also see him from the point of view of Melville looking over his shoulder with a novelist’s eye. Paradoxically, this doubling nature of the narrative adds to rather than detracts from the believability of what we are reading, since again it fits into a multiple narrative which aims to give us a sense of the uncertainty both of human perception and judgement of others, and of identity itself. It mimics the complicated way in which we see the world and ourselves.

Apart from this being our first sighting of the vaunted Ahab, it is a superb example of Melville’s descriptive powers, a major element in the readerly pleasure of the novel. We see Ahab through Ishmael’s terrified eyes, but we also see him from the point of view of Melville looking over his shoulder with a novelist’s eye. Paradoxically, this doubling nature of the narrative adds to rather than detracts from the believability of what we are reading, since again it fits into a multiple narrative which aims to give us a sense of the uncertainty both of human perception and judgement of others, and of identity itself. It mimics the complicated way in which we see the world and ourselves.

This first sighting of Ahab is what we might call a realist one, even given the heightened nature of the language and the narrative unsettling. What follows is downright extraordinary. In Chapter 37 we suddenly enter the mind of Ahab himself. The scene is set as with stage directions in a play – (The cabin; by the stern windows; Ahab sitting alone, and gazing out.) – and as in a Shakespeare play, we have the tragic hero uttering his soliloquy. I will leave the reader to discover this extraordinary passage but it plays an important part in eliciting our sympathy for a character who otherwise might repel us. We see the same conflicting feelings enacted in the next chapter in first mate Starbuck’s innermost thoughts about his captain:

My soul is more than matched; she’s overmanned; and by a madman! Insufferable sting, that sanity should ground arms on such a field! But he drilled deep down, and blasted all reason out of me! I think I see his impious end; but feel I must help him to it.

The next few pages inhabit the second mate, Stubbs’s inner thoughts, and then comes the play proper, with the various sailors on watch sharing their thoughts. This reminds of nothing so much as the start of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, where the Drowned exchange memories from their places in the dreamy deep. I have no doubt but that Thomas was doing a bit of cribbing here a century on.

The individuals depicted in this scene are a microcosm of the crew of the Pequod, emphasizing the mixed race and mixed-society nature of the whaling crew. There’s Pip the ‘small black boy’, and by turns numerous Nantucket sailors, interspersed with Dutch, French, Iceland, Maltese, Sicilian, Long Island, Azore, China, Old Manx, Tahitan and Danish sailors. Not to mention the named harpooneers Tashtego and Daggoo, respectively (as we have been told earlier) an ‘unmixed Indian from … Martha’s Vineyard, where there still exists the last remnant of a village of red men’, and an African who has jumped on to a whaling ship from his native shore. (The third harpooner is Queegqueg who doesn’t appear in this scene.) The excitable dialogue between this motley crew as a squall approaches conveys both danger and camaraderie, and a sense of the conflict to come.

Melville makes that anticipated conflict Shakespearean in character whilst at the same time never glorifying his large cast of renegades. For all of them are both cast and outcast, all finding their place, their society and their meaning in the pursuit of the whale. And immediately after their almost merry interchange in the face of the storm, now enters the great whale.

As much as Ahab has been anticipated, so Moby Dick has occupied the imagination of the novel’s characters, and of its readers from our first sighting of the novel’s title. Chapter 41 comes to close quarters with the significance of the great white whale, noting both the supernatural qualities that had been attributed to him, and the natural defining characteristics that made him unique – ‘a peculiar snow-white wrinkled forehead, and a high pyramidical white hump’:

The rest of his body was so streaked, and spotted, and marbled with the same shrouded hue, that, in the end, he had gained his distinctive appellation of the White Whale; a name, indeed, literally justified by his vivid aspect, when seen gliding at high noon through a dark blue sea, leaving a milky-way wake of creamy foam, all spangled with golden gleamings.

We learn that Ahab’s obsession with the White Whale stems from an encounter where ‘suddenly sweeping his sickle-shaped lower jaw beneath him, Moby Dick had reaped away Ahab’s leg, as a mower a blade of grass in a field.’ The language is Biblical and fraught with the same meaning. Ahab has, we learn, ‘piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all general rage and hate felt by his own race from Adam down’. Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

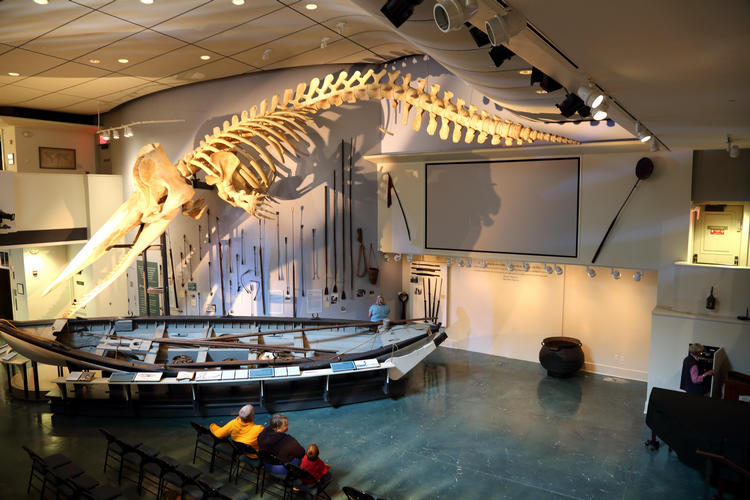

Here perhaps we need to pause to consider the dreadful trade of whaling upon which the novel hangs its central tragic conflict. To twenty-first century eyes, the pursuit of the noble and long-lived mammal the whale for mere commercial gain is clearly wrong; and the barbaric means by which the whale was hunted in the nineteenth-century, amply described in the novel, are horrific. Melville starts from a different position. He sees the battle between human and whale as a pitting of a lesser being against a greater, as nothing less than a grand conflict between man and nature. Ishmael certainly attempts a defence of whaling in the early chapters in practical terms, reminding us of the hypocrisy involved in opposing the hunting of the whale, given its underpinning importance both to commercial success and to many aspects of everyday life. Perhaps the most telling of his arguments is that the oil that anoints a monarch at their coronation is derived from the sperm-whale. (I don’t know if this is true, but it fits neatly into Melville’s hymn to democracy.) And in Chapter 82 he addresses ‘The Honor and Glory of Whaling’, giving its classical antecedents. But the real defence of whaling is not a physical but a metaphysical one. The battle between man and great beast is depicted as a tragic one. If man wins, the death of the whale is tragic. If the whale wins, the loss for man is tragic, whether it is loss of life, or loss of the quarry. He invokes great forces of nature, in the huge and extraordinary storms, and what feels like the will of the sea, against the fragility of the boats and the ridiculous smallness of the harpoons as the sailors set out to kill the whale.

Here perhaps we need to pause to consider the dreadful trade of whaling upon which the novel hangs its central tragic conflict. To twenty-first century eyes, the pursuit of the noble and long-lived mammal the whale for mere commercial gain is clearly wrong; and the barbaric means by which the whale was hunted in the nineteenth-century, amply described in the novel, are horrific. Melville starts from a different position. He sees the battle between human and whale as a pitting of a lesser being against a greater, as nothing less than a grand conflict between man and nature. Ishmael certainly attempts a defence of whaling in the early chapters in practical terms, reminding us of the hypocrisy involved in opposing the hunting of the whale, given its underpinning importance both to commercial success and to many aspects of everyday life. Perhaps the most telling of his arguments is that the oil that anoints a monarch at their coronation is derived from the sperm-whale. (I don’t know if this is true, but it fits neatly into Melville’s hymn to democracy.) And in Chapter 82 he addresses ‘The Honor and Glory of Whaling’, giving its classical antecedents. But the real defence of whaling is not a physical but a metaphysical one. The battle between man and great beast is depicted as a tragic one. If man wins, the death of the whale is tragic. If the whale wins, the loss for man is tragic, whether it is loss of life, or loss of the quarry. He invokes great forces of nature, in the huge and extraordinary storms, and what feels like the will of the sea, against the fragility of the boats and the ridiculous smallness of the harpoons as the sailors set out to kill the whale.

The resulting bloodiness is not however neglected. Chapters 61-70 give one unstinting account of what is involved in killing a whale and then butchering it for what is of value. Here is a brief taste:

The red tide now poured from all sides of the monster like brooks down a hill. His tormented body rolled not in brine but in blood, which bubbled and seethed for furlongs behind in their wake. The slanting sun playing upon this crimson pond in the sea, sent back its reflection into every face, so that they all glowed to each other like red men.

The passage as it continues calls to mind George Orwell’s ‘Shooting an Elephant’. Both call up the nobility of a great creature in the throes of death inflicted by that small being, a man. But while Orwell’s distaste changes his whole way of thinking, for Melville this is one part of a larger picture. We must see the horror of the killing, and the distress of the destroyed creature. But we must see too in equal balance the tragic role of man. This is what might test a twenty-first century sensibility, but it is the great feat of the novel that Melville persuades us that man’s part in this bloody struggle is also noble. Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

The apotheosis of this is of course Ahab’s pursuit of Moby Dick, which occupies the latter part of the novel. It is not to give much away to say that Moby Dick wins the day. That is inevitable in the way that Melville sets up Captain Ahab’s quest as that of a madman. But the way in which it is narrated shows us Melville’s descriptive and imaginative powers in a way that is almost as fearsome as the whale itself:

From the ship’s bows, nearly all the seamen now hung inactive: hammers, bits of plank, lances, and harpoons, mechanically retained in their hands, just as they had darted from their various employments; all their enchanted eyes intent upon the whale, which from side to side strangely vibrating his predestinating head, sent a broad band of overspreading semicircular foam before him as he rushed. Retribution, swift vengeance, eternal malice were in his whole aspect, and spite of all that mortal man could do, the solid white buttress of his forehead smote the ship’s starboard bow, till men and timbers reeled. Some fell flat upon their faces. Like dislodged trucks the heads of the harpooneers aloft shook on their bull-like necks. Through the breach, they heard the waters pour, as mountain torrents down a flume.

Moby Dick is a massive novel as befits its whale hero. And here I wonder if the size of the whale is part of the heroism inhering in this story, and attributed both to Ahab and his counterpart Moby Dick; and if so, whether this is something to question. Sheer size is a feature of the American aesthetic, whether we are looking at the American sublime in painting, or the big canvases of the Abstract Expressionists (both perhaps deriving from the extraordinariness of the landscape), or the great girth of the great American novel. I confess myself, on occasions anyway, seduced by that size, even if I see the objections to it. Certainly in the case of the novel Moby Dick, the size is necessary to encompass the many and shifting points of view, and the grandeur of the subject. It also makes for a wonderfully immersive and captivating read, full of wit, information, imagination and, above all, a sympathy which is both human and beyond the human. Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

Moby Dick is a massive novel as befits its whale hero. And here I wonder if the size of the whale is part of the heroism inhering in this story, and attributed both to Ahab and his counterpart Moby Dick; and if so, whether this is something to question. Sheer size is a feature of the American aesthetic, whether we are looking at the American sublime in painting, or the big canvases of the Abstract Expressionists (both perhaps deriving from the extraordinariness of the landscape), or the great girth of the great American novel. I confess myself, on occasions anyway, seduced by that size, even if I see the objections to it. Certainly in the case of the novel Moby Dick, the size is necessary to encompass the many and shifting points of view, and the grandeur of the subject. It also makes for a wonderfully immersive and captivating read, full of wit, information, imagination and, above all, a sympathy which is both human and beyond the human. Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

Now, to those twenty-first century readings. ‘Queering the Dick: Moby-Dick as a Coming-Out Narrative’, an undergraduate essay by Ryan Brady, 2016, gives a flavour of queer readings of the novel, which certainly can find textual underpinning for their interpretations. There’s not a woman in the text, except for distant wives briefly referred to, and emotional and sensual links are made, as we have seen, between men, that resemble those between men and women. The early passages, where even a form of marriage is conducted between Ishmael and Queegqueg – ‘when our smoke was over, he pressed his forehead against mine, clasped me round the waist, and said that henceforth we were married; meaning, in his country’s phrase, that we were bosom friends’ – are adduced to support such readings. My only proviso here is that a ‘coming-out’ reading is reductive in the sense that it is singular and excludes the multifarious dimensions that I have suggested are central to the novel. The same can be said of ‘green’ readings of the novel, from an environmentalist point of view. Pinning a flag of one colour – even be it a rainbow flag – to Moby Dick is to mistake it. That great craft sails under all colours.

I mentioned earlier the modernist echoes in Moby Dick. Virginia Woolf was an admirer, and read the novel more than once, first in 1922 as she notes in her Diary of February of that year, and later in the 1920s when she mentions it in ‘Phases of Fiction’ (1929); she was at the same time writing The Waves. Woolf’s writing was certainly underpinned by her awareness of – in Ishmael’s words – ‘the endlessness, yea, the intolerableness of all earthly effort’. Her biographer Lyndall Gordon suggests that Moby Dick might be the derivation of her remark in her 1926 Diary of the glimpse of ‘a fin rising on a wide blank sea’, an alarm and an inspiration. She was writing To the Lighthouse that year. The sea was both real and metaphorical to her as it was to Melville. Nothing could be further from whaling horrors than the calm seas leading to the lighthouse; but both saw the existential abyss, whether in the swirling ocean viewed from the masthead or in that ‘wide blank sea’. And both felt the quiver of that fin rising, summoning – what? Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

But the modernist take might be reductive too. I want to say to a new reader (or even an old one) – plunge in to this glorious ocean of a novel and let yourself be taken by its many currents. Whatever else it is, it’s a joy to read.

Main image: A diving albino Sperm Whale. Credit: Andrea Izzotti / Alamy Stock Photo

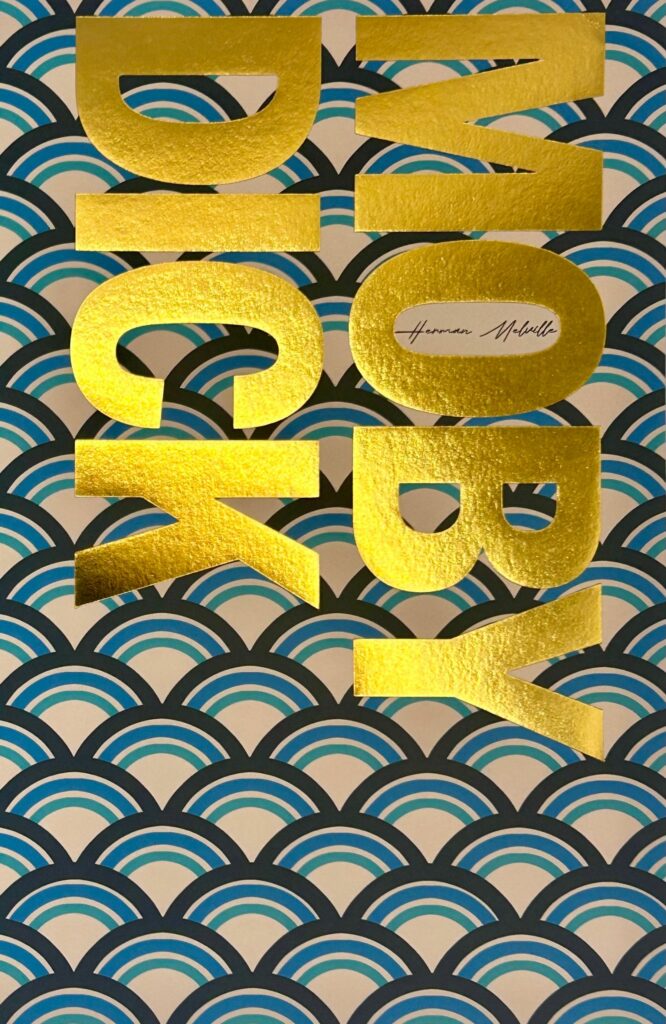

Image 1 above: Our classic edition of Moby Dick which can be found, along with our Collector’s Edition version, here: Melville Herman – Wordsworth Editions

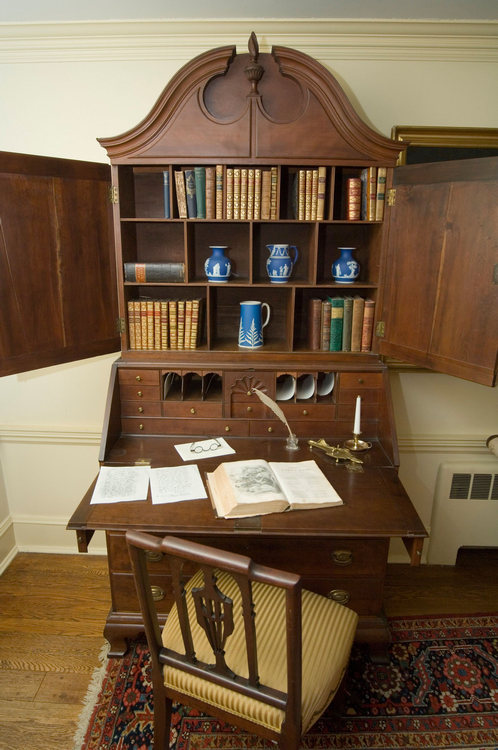

Image 2 above: Desk in “Arrowhead,” Pittsfield, Mass., the home of Herman Melville from 1850 to 1862. Credit: Universal Images Group North America LLC / DeAgostini / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Seamen’s Bethel at the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, New Bedford, Massachusetts on which the Seaman’s Chapel in the book is based. Credit: Stan Tess / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Whales by an ice floe, 1830-1860. Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: ‘Cutting in’ the whale at the commercial wharf Nantucket, 1867?-1890? Credit: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 6 above: Sperm whale skeleton, Nantucket Whaling Museum. Credit: Vicki Beaver / Alamy Stock Photo

For more on the life and works of Herman Melville, visit: The Melville Society

Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick

Books associated with this article

Moby Dick

Herman Melville