How Rudyard Kipling helped make the modern Disney

Parker Lancaster analyses the links between the famous author and the entertainment conglomerate.

It’s no secret that people love Disney. Obsessive Disney Disorder, or ODD, is a real thing. I’ve witnessed it personally.

But not all Disney is alike, even for the die-hard fans. To illustrate my point, let’s take a look at two different lists.

List the first: Westward Ho the Wagons, Johnny Tremain, The Sword and the Rose, Tonka, Greyfriars Bobby, The Three Lives of Thomasina, and The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin.

List the second: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Bambi, Dumbo, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and The Jungle Book.

The first list probably made your eyes glaze over, and possibly even made you fall asleep, while you likely noticed the pattern in the second list by the time you got to Pinocchio.

They’re all classic Disney animated films, of course, but it may surprise you to learn the first list also consists entirely of Disney feature films. You might consider them part of Walt Disney Pictures’ awkward teenage years. And that was just a small selection. There are more Disney films you’ve probably never even heard of, especially if you’re under 60. A lot more.

Almost everything we associate most with Disney, from the films to the songs to the theme park rides, revolves around its canon of animated films. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s by design that Disney has consistently put far more resources into the production of its animated films than its live-action or subsidiary studio films.

And as CGI has entirely supplanted hand-drawn animation, production and advertising budgets for their tentpole animated films routinely exceed $300 million (an eye-popping figure when compared to Disney’s first feature, Snow White, with an inflation-adjusted budget of $33 million).

Disney animation has a paradoxically massive cult following that no other film studio can boast. When was the last time you had a debate with a friend about which Universal Studios film was the best?

Have you ever heard anyone say, “I just can’t wait to see what Columbia Pictures puts out next!”?

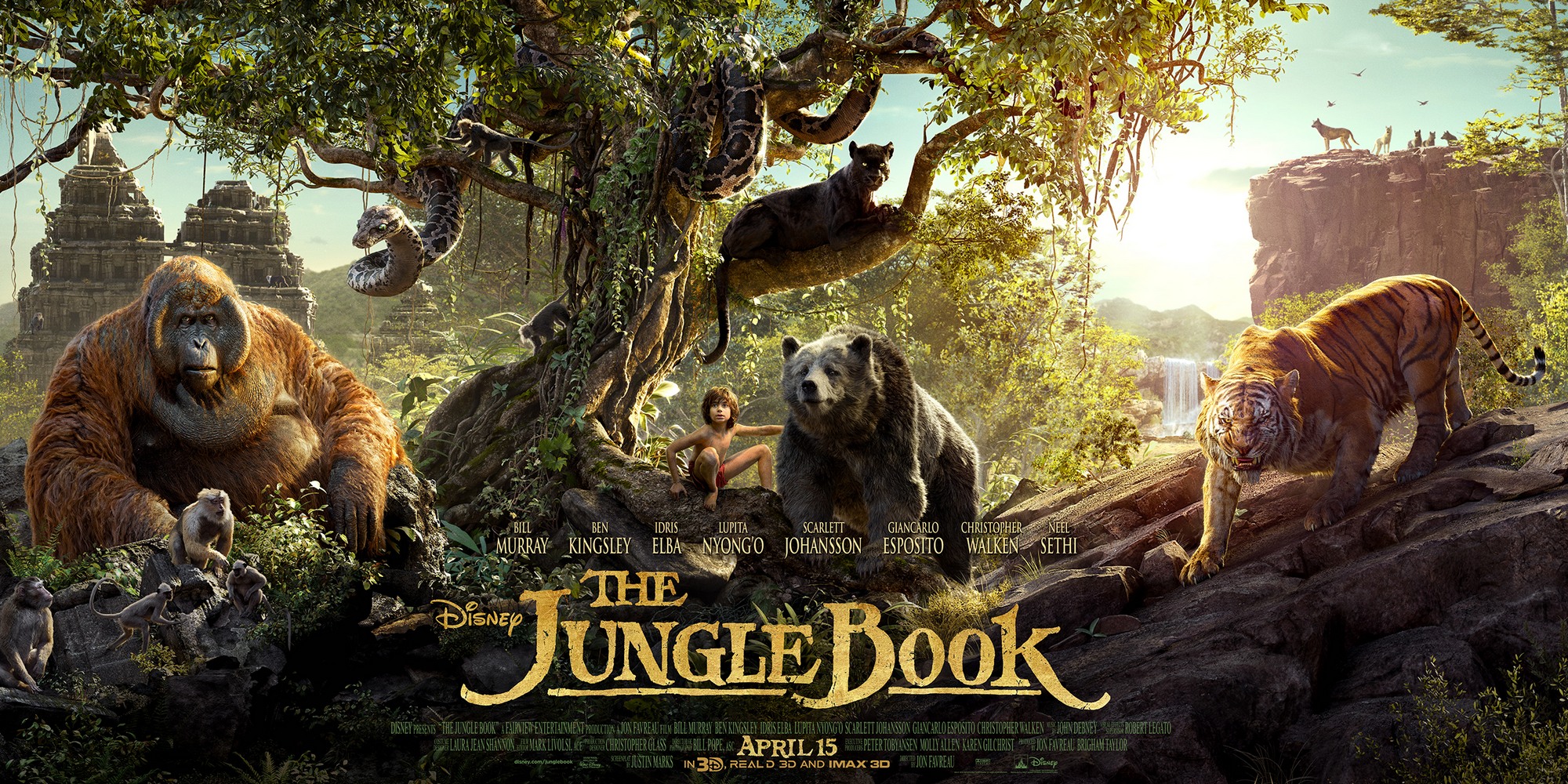

It’s worth noting that the Mouse House, now a global entertainment juggernaut with assets totalling $90 billion (Dr Evil could have just asked for ownership of Disney), has only ever adapted one original property for the screen three times: Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

Jon Favreau’s interpretation of is now gracing the screen in 57 countries, and Kipling’s celebrated stories are back in the spotlight. Or, to be more precise, about three of the Mowgli stories are back in the spotlight. Now that three generations are singing ‘Bare Necessities’ and ‘I Wanna Be Like You’ and Mowgli the man-cub is a household name in the greater part of the Western world, Kipling deserves special mention for just how distinguished a writer he was in comparison to all the other authors Disney has adapted. And for writing children’s fiction in a way that may have influenced the entire Disney aesthetic much more than anyone has given him credit for.

It can be said without exaggeration that Kipling is far and away the most broadly accomplished author to have had any association with Walt Disney or any part of his entertainment empire, past or present.

Even among the pantheon of such giants of literature, children’s fiction, and fairy and folk tales as Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, Washington Irving, Hans Christian Andersen, Robert Louis Stevenson, Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo, Lewis Carroll, J.M. Barrie, and T.H. White, Kipling somehow reigns supreme in terms of sheer accomplishment with the written word (though I confess that Shakespeare, whose Hamlet loosely inspired The Lion King, is the only author I will refrain from listing here as being “less accomplished” than Kipling, both in order to maintain some semblance of credibility and to prevent being immolated in the town square by a pitchfork-wielding angry mob, which I myself would be tempted to join for my hubris in espousing such blasphemy).

It’s a rare feat for a revered novelist to also be a celebrated poet. It’s also rare for a prolific and lauded writer of short fiction to be a journalist and newspaper editor. Kipling was all of the above. He was even a playwright if you count his unpublished and unproduced adaptation for the stage, The Jungle Play, which was thought lost for over 100 years.

He has been praised in varying degrees and cited as an influence by such writers and luminaries as Ernest Hemingway, and T.S. Eliot (who wrote in the essay The Unfading Genius of Rudyard Kipling that “it is a kind of obligation…to testify for [him] whenever the opportunity presents itself”), Maya Angelou, Arundhati Roy, Aung San Suu Kyi, and W. Somerset Maugham (who thought he was the greatest short story writer of all time), among many others.

Kipling had his share of admirers in academia, politics, and high society as well. He was nurtured in an atmosphere conducive to both the arts and a love of the British power structure, as his father was both the curator of the Lahore Museum and friends with Robert Bulwer-Lutton, who would go on to become the Viceroy of India and even crown Queen Victoria as its Empress.

Kipling was an honorary fellow of Magdalene College, Cambridge. He was elected Rector of the University of St. Andrews. He turned down both a knighthood and the title of Poet Laureate to the British Empire. He has an official society dedicated to his life and works that exists to this day. He was close friends with Henry James (who called him “the most complete man of genius I have ever known”), quintessential imperialist Cecil Rhodes, and Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, which cited The Jungle Book and Kim liberally in its founding documents and recruited Kipling to write the official song of the Boy Scouts, A Boy Scouts’ Patrol Song.

Some of Kipling’s original manuscripts are currently housed in the British Museum and the Bodleian Library. He personally corresponded with the likes of Sir Ernest Shackleton, H.G. Wells, Joseph Conrad, and Winston Churchill. And as a feather in his cap, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907 as its eighth recipient, was the first to win for work in the English language, and was the first to win for the triple categories of novel, short story, and poetry.

It is important to note, however, that aside from Kipling’s formidable resume and accolades, he also had the rare honour of being one of the most divisive, contradictory, and controversial authors in modern history. While Kipling rose to celebrity status among both the general public and the literary establishment in his twenties, his troubling views on race, suffrage, imperialism, and democracy ultimately left him an outcast among the critics.

He was both beloved and derided, adored and abhorred, and often by the same person at various times. His contradictory dual legacy as a brilliant writer and as a champion of lost and disgraceful causes has been remarked upon by the likes of Virginia Woolf, Robert Graves, Salman Rushdie, George Orwell, Edward Said, and Christopher Hitchens.

The Jungle Book and The Second Jungle Book do indeed occasionally stray into questionable territory. Her Majesty’s Servants, The Miracle of Purun Bhagat, The Undertakers, and Letting in the Jungle all stray from the simplicity of most of Mowgli’s adventures and offer up problematic conceptions of Indian people and society, and Kipling’s prescription for its ills: blind obedience to British colonial rule.

Perhaps it’s a testament to Kipling’s sheer command of the English language and storytelling ability that the same man who wrote The White Man’s Burden, a wholehearted defence of America’s invasion and colonisation of the Philippines, has also enchanted hundreds of millions of readers and film audiences of diverse ethnic backgrounds around the world with what is essentially a Bildungsroman about a boy trying to find his place in the world.

Books associated with this article

The Jungle Book (Collector’s Edition)

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book (Exclusive Edition)

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book & The Second Jungle Book

Rudyard Kipling