Book of the Week: The Scarlet Letter

The Scarlet Letter: Mia Rocquemore looks at Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic novel set in the Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony in the mid-1700s

A novel that combines spectacle with secret, the supernatural with bitter reality, and editorial authority with subjective narration, Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter demands a psychological reading. Its characters are so complex, their motivations and desires hidden from each other, the reader and ostensibly from the author himself, that we are compelled to view them in part as psychological case studies. This is no doubt what has made the book a constant feature in English Literature syllabuses, and accounts for the hundreds of academic papers written on the inner workings of both its characters and author alike.

The psychological effects of guilt, repression and shame are central to understanding the novel, and Pearl, “that little creature, whose innocent life had sprung, by the inscrutable decree of Providence, a lovely and immortal flower, out of the rank luxuriance of a guilty passion”, serves as their embodiment. The metaphor is not disguised. Hawthorne states that she is “the scarlet letter in another form; the scarlet letter endowed in life”. Hester holds her child at her breast besides the symbol she is forced to wear; when Pearl grows she even dresses her in red. The fact that Pearl is “the object of her affection and the emblem of her guilt and torture” is plain.

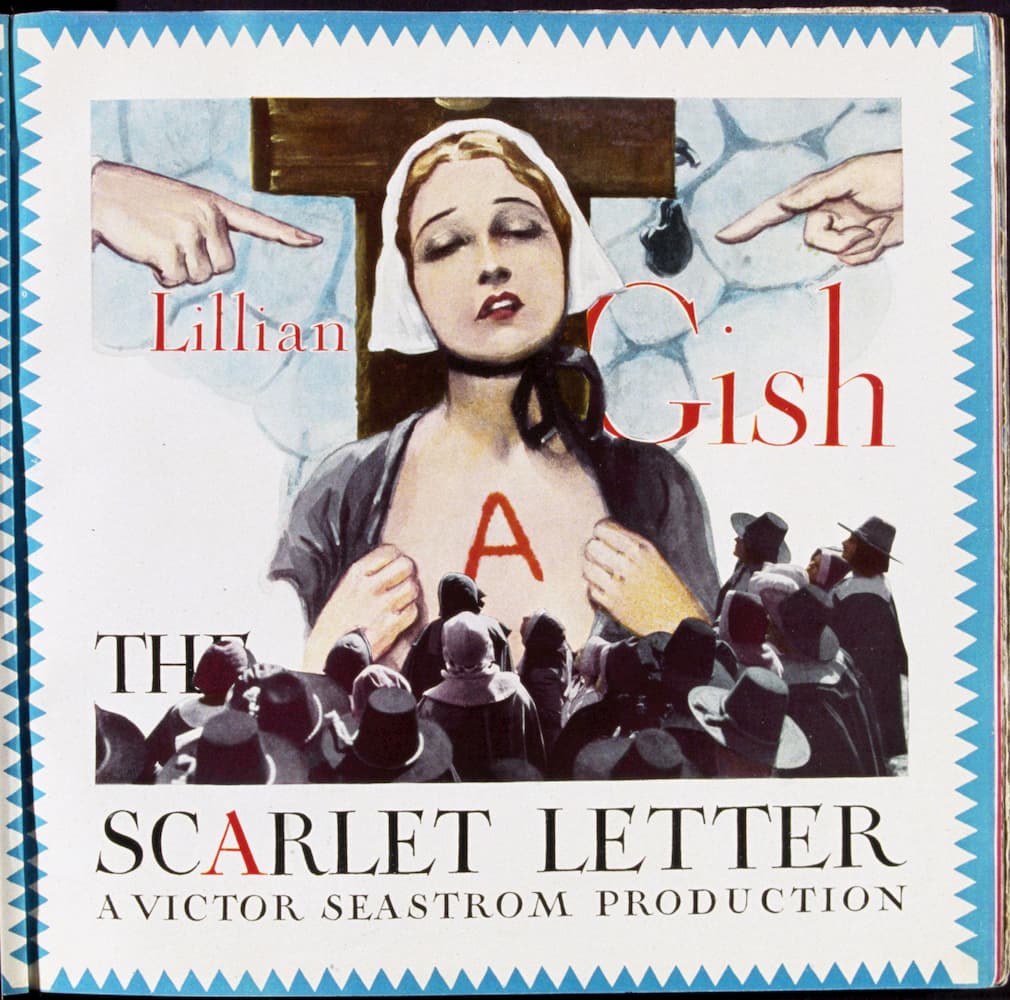

Poster for the 1926 MGM film starring Lillian Gish

Hester and Pearl’s relationship is one of particular interest because of the conflicting emotions the mother has towards this reminder of her disgrace. “She knew that her deed had been evil; she could have no faith, therefore, that its result would be good. Day after day, she looked fearfully into the child’s expanding nature, ever dreading to detect some dark and wild peculiarity, that should correspond with the guiltiness to which she owed her being.” Indeed Pearl soon becomes quite the little terror. From violence against small animals and other children to sudden and unexpected changes in temperament, the little girl torments her mother.

Here is clearly a case of the ‘sins of the father’. But perhaps the central question to be asked is whether Pearl’s unnatural and unnerving, even satanic, character is a straightforward matter of a wrongdoing producing an inherent wrongdoer, or whether Hester’s attitude and apprehension towards her child since birth creates the monster she fears. On the one hand, Hawthorne suggests that there is something fundamentally nefarious within her:

“Pearl was a born outcast of the infantile world. An imp of evil, emblem and product of sin, she had no right among christened infants… If spoken to, she would not speak again. If the children gathered about her, as they sometimes did, Pearl would grow positively terrible in her puny wrath, snatching up stones to fling at them, with shrill, incoherent exclamations, that made her mother tremble, because they had so much the sound of a witch’s anathemas in some unknown tongue.”

On the other, the fact of growing up in a “circle of seclusion from human society” seems bound to leave its mark on a developing child. Moreover, Hester’s paranoia about the effects of her exile and adultery on Pearl appear to be projected onto her, distorting innocent childlike behaviours into something much more sinister. From the moment the baby first touches the scarlet letter embroidered onto her mother’s dress, “Hester had never felt a moment’s safety; not a moment’s calm enjoyment of her”. Henceforth, after the living and the emblematic symbols of her adultery are first viscerally connected, Hester begins to interpret Pearl’s every action as a reminder of, or punishment for, her sin.

“She seemed rather an airy sprite, which, after playing its fantastic sports for a little while upon the cottage floor, would flit away with a mocking smile…Beholding it, Hester was constrained to rush towards the child,—to pursue the little elf in the flight which she invariably began,—to snatch her to her bosom, with a close pressure and earnest kisses,—not so much from overflowing love, as to assure herself that Pearl was flesh and blood, and not utterly delusive.” Yet could this not simply be the natural games of a mischievous infant, misinterpreted by a mother looking for evil?

Likewise, when she sees in the reflection of a brook “the shadowy wrath of Pearl’s image, crowned and girdled with flowers, but stamping its foot, wildly gesticulating, and, in the midst of all, still pointing its small forefinger at Hester’s bosom”, might she not be taking a child’s demands for its mother’s attention as a malevolent and threatening reminder of the brand of shame on her chest? These questions are magnified by the ambiguity of the novel’s narration.

Hester’s interactions with Pearl are often framed in ambiguity: the “mother could have fancied that the child had absorbed [the sunlight] into herself”; she sees her “now like a real child, now like a child’s spirit”; “she fancied that she beheld…a face, fiend-like, full of smiling malice…It was as if an evil spirit possessed the child, and had just then peeped forth in mockery”. Hawthorne’s frequent use of phrases such as “she fancied”, “she doubted” and “as if” point towards the uncertainties and instability of Hester’s perceptions. Indeed at times these verge on hallucinations and dangerous impulses:

“There was wild and ghastly scenery all around her, and a home and comfort nowhere. At times, a fearful doubt strove to possess her soul, whether it were not better to send Pearl at once to heaven, and go herself to such futurity as Eternal Justice should provide.”

Such uncertainty is amplified by the narrator’s own role in the story. The lengthy introduction to the novel introduces the narrator, who shares many traits with Nathaniel Hawthorne himself, and who discovers in the Customs House at Salem a hundred-year-old historical account of the affair of the scarlet letter, which had occurred the previous century. The narrator, despite professing doubts about his own writing abilities, decides to undertake a fictional retelling of the affair, thus producing the novel, The Scarlet Letter. These layers of narrative ambiguity, of which the reader is reminded by syntactical structures revolving around the terms “whether…or…” and “it seemed”, force us to question whether the demonic presentation of Pearl is an accurate reflection of the child’s nature, or an interpretation distorted by so many unreliable perceptive strata.

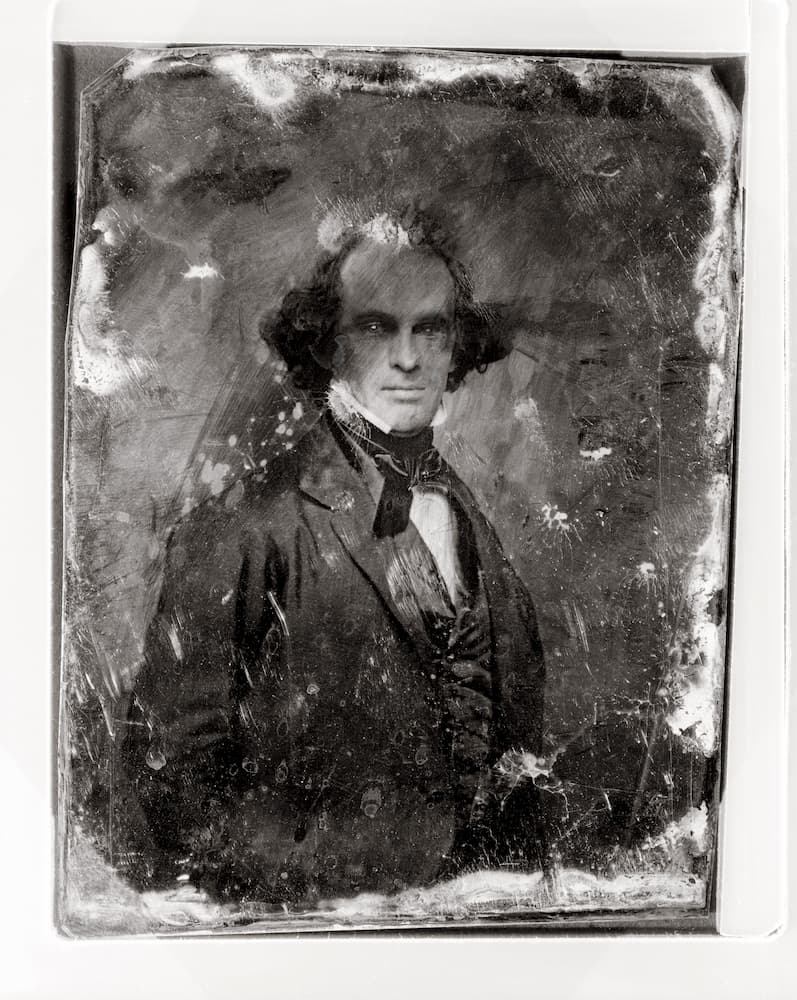

Nathaniel Hawthorne. Daguerrotype by anonymous photographer c.1850

Distortion is cast on Pearl from all sides: by society, which sees the child born of adultery as an aberration, herself blameworthy for and tarred by the sin that begot her; by Dimmesdale, her absent father, who covertly acknowledges his position but swears that “the daylight of this world shall not see” his paternal connection; by her own mother, to whom she is a constant reminder of her shame; and by the narrator, who deliberately shows her as both demonised and demon. Her name has often been taken as a symbol of purity, white and precious, calculated to contrast Hester’s sin and symbol. The iridescence immediately associated with pearls, however, may also reflect the spectrum of forms she takes on depending on the gaze and attitude levelled at her.

Pearl is liberated from these sources of distortion one by one. Dimmesdale finally confesses his relation to the child before the town and swiftly dies; soon Chillingworth, Hester’s husband who had sworn vengeance for her adultery, also dies and leaves Pearl a substantial inheritance, allowing the mother and child to leave the Puritan community of New England and travel to Europe. Finally Hester returns to Salem, leaving Pearl “not only alive, but married, and happy” in England. The mother, with the living symbol of her sin absent, is able to resume “a more real life”, while the daughter, safely removed from the depleting forces of Salem, her family and the narrator, who “[n]ever learned, with the fulness of perfect certainty” what became of her, is finally able to live a contented life unhindered by the misperceptions of those around her.

Hawthorne himself was a religious man, with a great faith in and gratitude towards God, but he eschewed organised religion throughout his life, disavowing his own Puritan roots, criticising the Catholic church, and rebuking the Transcendentalist movement to which his wife belonged. His letters speak of a personal relationship with God, and although sin and shame appear to have blighted him as they do his characters, he did not exhibit his turmoil in the public sphere, except arguably through his writings, but was known to be withdrawn and veiled, often literally. The Fall of Man and human imperfection was, for Hawthorne, a demon to be wrestled with in private, not to be placed under the control or regulation of an earthly authority. This opinion can be applied directly to the story of The Scarlet Letter, in which external pressure and societal standards drain characters of their humanity. It is only when they relieve themselves from these debilitating forces that they can become psychologically healthy and at peace.

Main image: 1995 Entertainment/Hollywood film with Demi Moore and Gary Oldman. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Poster for the 1926 MGM film starring Lillian Gish. Credit: Entertainment Pictures / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Nathaniel Hawthorne. Daguerrotype by anonymous photographer c.1850 Credit: ARCHIVIO GBB / Alamy Stock Photo

For more information on the life and works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, visit The Nathaniel Hawthorne Society

Our edition can be found here: Nathaniel Hawthorne

Books associated with this article