Book of the Week: The Woman in White

In the first of two blogs on Wilkie Collins, Stephen Carver looks at the novel the author considered to be his greatest achievement. The Woman in White

Much as letters were carefully preserved in the 19th century, it was the custom of the children of eminent Victorians to dutifully produce a biography of their departed parent. This was usually but not exclusively their father – Sara Coleridge, for example, wrote a beautiful memoir of her mother – to be placed over the grave, so to speak, along with an overly elaborate monument. While often quite turgid panegyrics, these biographies are nonetheless a wonderful resource for historians willing to seek them out and trawl through them. Thus, in his Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais (1899), John Guille Millais relates the following anecdote from 1858. His father – the Pre-Raphaelite painter – had been walking home from a dinner party accompanied by the author Wilkie Collins and his younger brother Charles, through the dimly lit and in those days semi-rural roads and lanes of North London…

It was a beautiful moonlight night in the summertime, and as the three friends walked along chatting gaily together, they were suddenly arrested by a piercing scream coming from the garden of a villa close at hand. It was evidently the cry of a woman in distress; and while pausing to consider what they should do, the iron gate leading to the garden was dashed open, and from it came the figure of a young and very beautiful woman dressed in flowing white robes that shone in the moonlight. She seemed to float rather than to run in their direction, and, on coming up to the three young men, she paused for a moment in an attitude of supplication and terror. Then, seeming to recollect herself, she suddenly moved on and vanished in the shadows cast upon the road.

‘What a lovely woman!’ was all Millais could say.

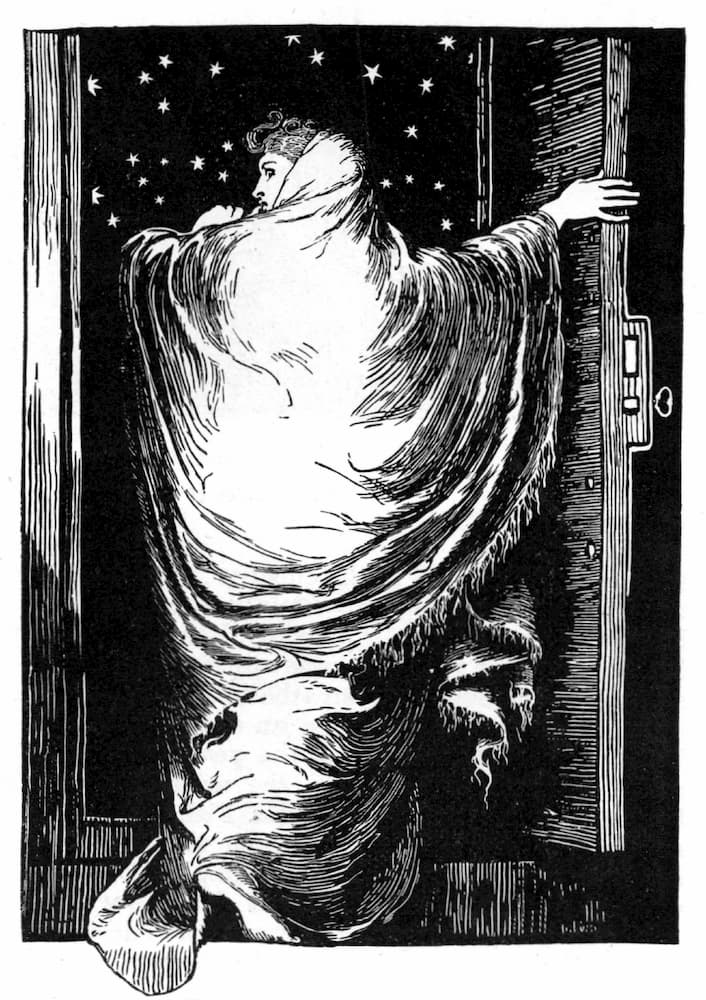

Illustration for the poster of the 1871 stage version

‘I must see who she is and what’s the matter,’ said Wilkie Collins as, without another word, he dashed off after her. His two companions waited in vain for his return, and next day, when they met again, he seemed indisposed to talk of his adventure. They gathered from him, however, that he had come up with the lovely fugitive and had heard from her own lips the history of her life and the cause of her sudden flight. She was a young lady of good birth and position, who had accidentally fallen into the hands of a man living in a villa in Regent’s Park. There for many months he kept her prisoner under threats and mesmeric influence of so alarming a character that she dared not attempt to escape, until, in sheer desperation, she fled from the brute, who, with a poker in his hand, threatened to dash her brains out.

Millais Jr. concludes the episode: ‘Her subsequent history, interesting as it is, is not for these pages.’ As ever in these Victorian memoirs, propriety always stays the chronicler’s hand just as they are getting to the good bits. Millais’ tact here is because of the almost certainly apocryphal story that the woman in question was Caroline Graves, a lower-middle-class widow and mother with whom Collins lived but never married from 1858 to his death in 1889, barring a brief separation during which Caroline married a plumber before returning to Collins. Collins had further scandalised his peers in 1868 when he also took a mistress, Martha Rudd, a young working-class woman from Norfolk, with whom he had three children.

That Collins might have met the love of his life under such romantic circumstances is a nice story, even if not to be told officially at the time. In reality, Caroline kept a modest shop near the house Collins shared with his brother and mother in Hanover Terrace, and it is much more likely that he met her buying candles. Similarly, the identity of the original ‘Woman in White’ was probably known only to herself and, possibly, Collins, and the two may well have never met again. The story was nonetheless (allegedly) perpetuated by Dickens’ daughter Kate, who had been married to Collins’ younger brother. According to her friend Gladys Storey, Kate had told her that ‘this Woman in White so gallantly rescued by Wilkie Collins was the same lady who henceforth lived with him.’ This Storey duly recorded in her memoir of Kate, Dickens and Daughter (1939), written ten years after her friend had died.

Perhaps Caroline was the ‘Woman in White’, perhaps she wasn’t. As Lady Clarinda asserts in Crotchet Castle, ‘History is but a tiresome thing in itself; it becomes more agreeable the more romance is mixed up with it.’ The same goes for literary biography. And perhaps because of his temperament as much as his role in the development of the English novel – mentored by Dickens, herald of the likes of Thomas Hardy and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – Wilkie Collins was a master of both romance and realism. In fact, he could blend the forms with such alchemical precision it was far from obvious where one ended and the other began. And regardless of the true identity and history of the ‘very beautiful woman dressed in flowing white robes’, she was to become immortalised in what many readers and literary scholars alike believe to be Collins’ finest work, The Woman in White. Whoever she was, she had certainly made an impression on Wilkie Collins.

Published in 1860, The Woman in White was Collins’ fifth novel. It followed Antonina, or the Fall of Rome (1850), a historical novel in the manner of Edward Bulwer Lytton; Basil (1852), a tale of social class and sexual obsession that was praised by Dickens; the Dickensian Hide and Seek (1854), which Dickens described as ‘the cleverest novel I have ever seen written by a new hand’; and the psychological mystery The Dead Secret (1856). Collins had been learning his trade. Leaving aside the anomalous Antonia, which harks back to the 1840s vogue for historical romance, Basil, Hide and Seek, and The Dead Secret can all be read as early examples of what came to be known as ‘Sensation Fiction’, although the term had yet to be coined. Basil, in fact, caused quite a stir in its day for its depiction of the secret marriage of the upper-class hero to the teenage daughter of a linen draper who is then seduced by his father’s clerk. But despite Dickens’ praise, Collins had yet to break through in the Darwinian world of mid-Victorian popular fiction.

Collins shared Dickens’ passion for amateur dramatics and the two writers were introduced by a mutual friend, the artist Augustus Egg, while Dickens was producing Lytton’s comedy Not So Bad as We Seem for the stage in the spring of 1851. Collins landed a small part, and a friendship began that would endure until Dickens’ death in 1870. Collins was soon a regular contributor to Household Words, becoming a staff writer in 1856. When Dickens fell out with his publisher Bradbury and Evans and Household Words folded to be replaced by All the Year Round, Collins went with him. The Woman in White was serialised in 20 parts in All the Year Round between November 1859 and April 1860, appearing concurrently in the US in Harper’s Magazine. When The Woman in White began, Collins was an established contributor to the magazine but still something of a journeyman author; by the end of the serial, he was one of the most popular novelists of the day. ‘There can be no doubt that it is a very great advance on all your former writing,’ Dickens wrote to him, ‘The story is very interesting and the writing of it admirable.’

All the Year Round had hit the ground running with Dickens’ flagship serial A Tale of Two Cities, but circulation rose when The Woman in White followed it and fell again when it ended. Queues formed outside the offices when the next edition was due out, and a cottage industry of unlicensed ‘Woman in White’ products sprang up to satisfy the public craze, including clothes, cosmetics, toiletries, and ceramics, while music shops supplied sheet music for themed waltzes and quadrilles. When The Woman in White was published as a ‘triple-decker’ (three volume) novel, it went through four editions in the first month, the first edition selling out on the day of publication. William Gladstone cancelled a social engagement so he could keep reading and Prince Albert gifted it to friends. ‘Walter’ – the name of the novel’s hero – became a fashionable name for babies, and painters filled galleries with portraits of women in white gowns. Collins was courted by publishers, Smith and Elder offering £5,000 for his next novel. ‘FIVE THOUSAND POUNDS!!!!!!’ he wrote to his mother, ‘Ha! ha! ha! Five thousand pounds, for nine months or, at most a year’s work – nobody but Dickens has made as much.’ The Woman in White was certainly a page-turner, and so it remains. It is not difficult to imagine the mesmeric effect the story had on Victorian readers and the publishers who watched and fed the public taste.

The design and implementation of the novel is precise and beautiful. As contemporary reviewer Alexander Smith observed, ‘every trifling incident is charged with an oppressive importance; if a tea-cup is broken, it has a meaning, it is a link in a chain; you are certain to hear of it afterwards.’ This meticulous plotting – which Dickens clearly learned from in his later novels – is matched by a genius for character creation and a wry sense of subversion beneath the veneer of Victorian respectability, a duality much like the novelist himself. Collins was raffish and bohemian, romantic and spontaneous, the opium-addicted son of an artist who spent much of his youth in France and Italy and cheerfully defied social convention. The novel therefore offers two sets of ‘heroes’. There is the notional protagonist, Walter Hartright, and his beautiful, innocent, and rather boring love interest, Laura Fairlie, whose fraught story arc moves towards a resolution that conforms to Victorian social norms and values. There is also the dashing and wicked Count Fosco, and the unconventional and brilliant – if rather manly – Marian Halcombe, representing respectively anarchy and feminism, and both given prominent voices in the narrative. Fosco, in fact, is allowed to put forward his own version of events in his own words, which are thoroughly unrepentant and seem to suggest that if one is daring and cunning enough, then crime really does pay.

After a couple of deceptively leisurely opening chapters in which the protagonist is introduced – Walter Hartright, a poor artist and drawing tutor – and his status quo disrupted by an intriguing job offer, triggering the novel, the first act concludes with a meeting very much like the one from the summer of 1858. As Walter wanders home from his mother’s house along the secluded Finchley Road on a sultry, moonlit summer’s night:

There, in the middle of the broad bright high-road—there, as if it had that moment sprung out of the earth or dropped from the heaven—stood the figure of a solitary Woman, dressed from head to foot in white garments, her face bent in grave inquiry on mine, her hand pointing to the dark cloud over London, as I faced her.

The moment is gothic. The encounter takes place ‘where four roads met’, a site at which murderers and suicides were traditionally buried, the crossroads intended to confuse unquiet spirits, who would be unable to choose a path. The word Walter chooses to describe the woman is ‘apparition’, and she doesn’t know which way to go either. ‘Is that the road to London?’ she asks. But this is not a ghost story, despite the novel’s evocative title. Legends of spectral ‘white ladies’ have been a staple of supernatural fiction and folklore since the Middle Ages, their appearance traditionally linked to an impending death. Collins was well aware of this, and the ghostly figure certainly assumes this role symbolically in the story, appearing – and just as quickly disappearing – at moments of impending crisis.

Her social rank is ambivalent, and the informed reader might think of Caroline Graves in Walter’s initial description:

There was nothing wild, nothing immodest in her manner: it was quiet and self-controlled, a little melancholy and a little touched by suspicion; not exactly the manner of a lady, and, at the same time, not the manner of a woman in the humblest rank of life.

Walter is therefore confident that this strange encounter is not to be transactional: ‘The one thing of which I felt certain was, that the grossest of mankind could not have misconstrued her motive in speaking, even at that suspiciously late hour and in that suspiciously lonely place.’ Rather, she is a damsel in distress, and just as Collins had helped the mystery woman on that fateful summer evening in 1858, Walter comes to the aid of her fictional counterpart:

The loneliness and helplessness of the woman touched me. The natural impulse to assist her and to spare her got the better of the judgment, the caution, the worldly tact, which an older, wiser, and colder man might have summoned to help him in this strange emergency.

She claims to have met with an accident and is lost. She has a friend in London, she says, if she can only find her way. Walter is clearly drawn to the woman, though his motives are unclear, or at least mixed: he is intrigued by the mystery of her unlikely presence, alone, in the middle of nowhere at night; he wants to help; he is captivated by her vulnerable, ethereal beauty. We don’t know, and Walter doesn’t know, but the dice are rolling. Nonetheless, he does ‘try and gain time by questioning her’ and is destined to fall in love with someone who looks very much like her so the frisson of desire cannot be easily denied. In this, creation probably resembles creator. Collins certainly liked the ladies and seemed to be attracted to those of a lower social class to himself. As Millais’ anecdote implied, Collins’ interest in the mystery woman had not been entirely chivalrous.

A cryptic conversation follows, in which the woman has to be reassured that Walter is not ‘a man of rank and title’, a class she seems to fear, one unnamed baronet in particular, while making him promise that he will not ‘interfere’ with her, that is impede her journey in any way. Walter assures her he is not and will not, and, fearing she might later have need of his help in London, he explains that he’s lately been engaged to tutor two young ladies in Cumberland and is leaving imminently. To his amazement, the woman replies that she went to school briefly in the village he’s moving to and speaks with great affection of the family that has engaged him, the Fairlies of Limmeridge House, though those she knew are now long dead. By now, they have reached gaslights and houses. Walter engages a cab for the woman in white and bids her farewell. He continues to walk home, wondering if the encounter had really happened, when an open chaise pulls up alongside a policeman across the road and asks if he’s seen a woman in white who’s escaped from an asylum. Walter says nothing. In the morning, he begins his journey to Limmeridge House and the main body of the story.

The identity of the ‘Woman in White’ is not, however, the mystery. Rather, she is a catalyst for a much more elaborate plot, a series of secrets and conspiracies that cross generations and into which Walter is shoved by the hand of authorial fate. Walter’s employer, Frederick Fairlie, is an indifferent and indolent hypochondriac who is guardian to his niece, Laura Fairlie, the heir to a considerable fortune. Walter is to tutor Laura and her elder half-sister and companion, Marian Halcombe, bothering their guardian as little as possible. Marian, whom he meets first, quickly befriends him. She is a prototypical ‘New Woman’, a literary ancestor of Stoker’s Mina Harker: highly intelligent, witty to the point of irreverence, and political in her frustration at the legal, social, and physical constraints imposed on her by gender. Unlike Laura, she has no inheritance and lives at the mercy of the Fairlies’ goodwill, being the daughter of Laura’s late mother from a previous marriage. Walter first sees her standing at a window and is ‘struck by the rare beauty of her form, and by the unaffected grace of her attitude.’ As she turns and approaches him, the spell is broken, at least as far as the male gaze is concerned:

The lady’s complexion was almost swarthy, and the dark down on her upper lip was almost a moustache. She had a large, firm, masculine mouth and jaw; prominent, piercing, resolute brown eyes; and thick, coal-black hair, growing unusually low down on her forehead. Her expression—bright, frank, and intelligent—appeared, while she was silent, to be altogether wanting in those feminine attractions of gentleness and pliability, without which the beauty of the handsomest woman alive is beauty incomplete. To see such a face as this set on shoulders that a sculptor would have longed to model … was to feel a sensation oddly akin to the helpless discomfort familiar to us all in sleep, when we recognise yet cannot reconcile the anomalies and contradictions of a dream.

Marian is not to be the love interest. Freed of this role, she later becomes Watson to Walter’s Sherlock Holmes, a fellow amateur investigator and confidante as the plot thickens. She loves a good mystery, and soon discovers the identity of the woman in white by going through her mother’s letters.

Laura is a much more conventional heroine of Victorian fiction:

Think of her as you thought of the first woman who quickened the pulses within you that the rest of her sex had no art to stir. Let the kind, candid blue eyes meet yours, as they met mine, with the one matchless look which we both remember so well. Let her voice speak the music that you once loved best, attuned as sweetly to your ear as to mine. Let her footstep, as she comes and goes, in these pages, be like that other footstep to whose airy fall your own heart once beat time. Take her as the visionary nursling of your own fancy; and she will grow upon you, all the more clearly, as the living woman who dwells in mine.

She is also the spitting image of the woman Walter met on the Finchley Road. Walter is quickly smitten, despite the obvious difference in social rank, and the grounds of Limmeridge House become Edenic as friendship and passion grow. But as is always the case, there is a serpent in the garden. Laura, Marian delicately reveals, is engaged to be married to Sir Percival Glyde, Baronet.

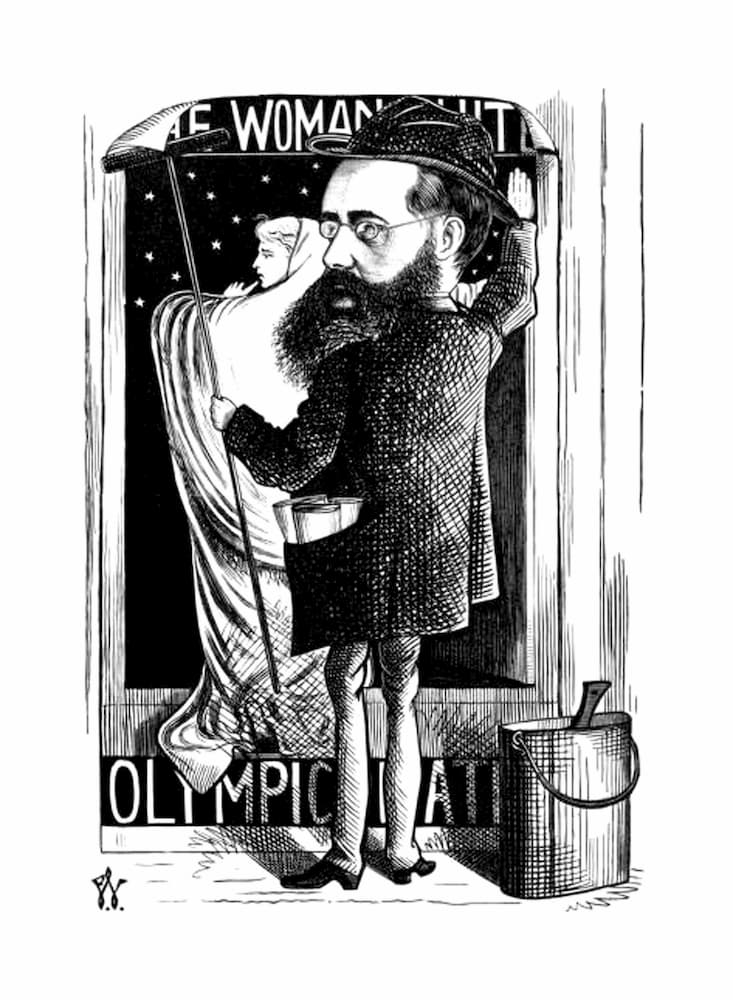

Drawing by Frederick Watty

Marian advises Walter to leave, but while he prepares to break his contract with Frederick Fairlie, local schoolchildren report seeing a ghostly woman haunting Limmeridge churchyard, ‘Arl in white – as a ghaist should be.’ At the same time, Laura receives a cryptic anonymous letter clearly warning her against marrying Glyde. In a moment of epiphany, Walter tells Marion that ‘the fancied ghost in the churchyard, and the writer of the anonymous letter, are one in the same person,’ the same woman he met on the road into London. Could it be Glyde that had the woman in white placed in the asylum, he wonders? But there is nothing he or Marian can do. Glyde will not release Laura from her promise, even when she confesses she loves another. Neither can her guardian be bothered with the family lawyer’s concerns over the financial terms of the marriage settlement, in which Glyde would receive her entire fortune if she died without leaving an heir. To get over his broken heart, Walter joins a scientific expedition to Central America, leaving those around Laura to pick up the narrative. And so, the first act closes, the pieces on the board developed. Walter’s knight has left the field, and only Marian stands between Laura and her new husband, and his sinister companion from Italy, Count Fosco, a ruthless and brilliant strategist that prefers animals to human beings. Fosco is captivated by Marian, however, who he views as his intellectual equal. And although Marian is granted lesser textual status than the more conventional and much less interesting Laura, we are left with the impression that she would be the hero were Fosco writing the account rather than Walter.

Then things get really complicated…

As the plot twists and turns, Collins uses the accounts of multiple point of view characters to tell the story over a more conventional unified narrative voice. He had trained (but never practiced) as a lawyer at his father’s insistence and, as he explained in a ‘Preamble’ to the novel:

The story here presented will be told by more than one pen, as the story of an offence against the laws is told in Court by more than one witness—with the same object, in both cases, to present the truth always in its most direct and most intelligible aspect; and to trace the course of one complete series of events, by making the persons who have been most closely connected with them, at each successive stage, relate their own experience, word for word.

Thus, ‘As the Judge might once have heard it, so the Reader shall hear it now.’ This, he explains, is to ensure that ‘No circumstance of importance, from the beginning to the end of the disclosure, shall be related on hearsay evidence.’ But this crafty claim to veracity also allows Collins to obscure and misdirect, while also showing key characters through the eyes of several people, all of whom offer very different portraits, leaving the reader to draw their own conclusions. Count Fosco, for example, is perceived by many to be a man of considerable charm and breeding. The novel is therefore subdivided into the following narrative fragments across three ‘epochs’ or parts, the common format of the Victorian serial, which was subsequently published as a novel in three volumes:

THE FIRST EPOCH

The Story Begun by Walter Hartright (of Clement’s Inn, Teacher of Drawing) [This is the part summarised above]

The Story Continued by Vincent Gilmore (of Chancery Lane, Solicitor).

The Story Continued by Marian Halcombe (in Extracts from her Diary).

THE SECOND EPOCH

The Story Continued by Marian Halcombe.

Postscript by a Sincere Friend. [Count Fosco writing in Marian’s diary]

The Story Continued by Frederick Fairlie, ESQ., of Limmeridge House.

The Story Continued by Eliza Michelson (Housekeeper at Blackwater Park).

THE STORY CONTINUED IN SEVERAL NARRATIVES

- The Narrative of Hester Pinhorn, Cook in the Service of Count Fosco. Taken down from her own statement.

- The Narrative of the Doctor.

- The Narrative of Jane Gould.

- The Narrative of the Tombstone.

- The Narrative of Walter Hartright.

THE THIRD EPOCH

The Story Continued by Walter Hartright.

The Story Continued by Mrs Catherick.

The Story Continued by Walter Hartright.

The Story Continued by Isidor, Ottavio, Baldassare Fosco.

The Story Concluded by Walter Hartright.

As well as having a legal format, this device is also gothic. In gothic fiction, multiple points of view are used to undermine set interpretation and unsettle the reader. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, for example, is framed by Captain Walton’s letters to his sister, while the main body of the text is Victor Frankenstein’s confession, which is, in turn, annexed mid-point by the first-person narrative of his creature. Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr. Hyde similarly offers a third person frame plus ‘Dr Lanyon’s Narrative’ and ‘Henry Jekyll’s Full Statement of the Case’. Stoker’s Dracula is the most complex of all, comprising letters, diaries, and journal entries from six point of view characters and a series of newspaper columns. This level of narrative fragmentation functions as a series of competing frames of explanation, creating a tension between natural and supernatural possibilities, like a series of witness testimonies in a complicated trial, just like Collins’ analogy. In The Woman in White, the effect is to build suspense to key-bending levels, with one narrative cutting across the other at a moment of extreme tension, until all the fragments finally come together only in climax and denouement. In a thriller, the effect is electric, even after all these years. Multiple points of view are also a feature of postmodern narratives, in which the mutable and fundamentally unstable nature of the ‘self’ (our individual conscious and unconscious identities) muddling along in a godless universe is reflected in the instability of the text. Obvious examples include the early novels of Thomas Pynchon – The Crying of Lot 49, V, and Gravity’s Rainbow – and Samuel Beckett’s ‘Trilogy’: Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable. It is probably a reach to suggest Collins had something similarly existential in mind, but The Woman in White is nonetheless a novel much concerned with psychology, from the extremes of the Victorian asylum to the instability of individual identity and the way we perceive ourselves and each other. Mrs Catherick, for example, has endured years of judgement and social ostracism to proudly reach a point in matronly middle age at which the vicar must always raise his hat when he sees her in the street. And just as it should be in all good mysteries, nobody is quite what they seem.

As a serial writer, Collins was also a master of the cliffhanger ending, of evocative ‘last turns’ that close one chapter while setting up the next. In Walter’s opening narrative, for example, there are such page-turning closers as:

‘Done! She has escaped from my Asylum. Don’t forget; a woman in white. Drive on.’

My introduction to Miss Fairlie was now close at hand; and, if Miss Halcombe’s search through her mother’s letters had produced the result which she anticipated, the time had come for clearing up the mystery of the woman in white.

She paused for a moment, and then answered, rather coldly— ‘Baronet, of course.’

The place looked lonelier than ever as I chose my position, and waited and watched, with my eyes on the white cross that rose over Mrs. Fairlie’s grave.

One farewell look, and the door had closed upon her—the great gulf of separation had opened between us—the image of Laura Fairlie was a memory of the past already.

You can feel the man reaching across time and grabbing us, which is why The Woman in White remains a popular novel to this day, in a limited Victorian literary pantheon in which a handful of novels become transcendent and iconic, for example Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Great Expectations, Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and Collins’ other famous novel, The Moonstone. Even if you’ve never read these books, you’re aware of them as part of our common cultural heritage; you’ll have some idea of the story and have probably seen a movie or a serial. There are just some classic novels that are endlessly dramatised, and The Woman in White is one of them. The BBC has been making it regularly since the first six-part serial in 1966. The next BBC adaptation was in 1982, with a stunning performance from Diana Quick as Marian. Then there was the 1997 version, with Andrew Lincoln as Walter, and Simon Callow making Count Fosco his own forever. The BBC remade it again in 2018 with a nice turn by Dougray Scott as Sir Percival Glyde. (There were also two Radio Four serials.) The novel has also been adapted for television in Italy, Germany, and Russia. There have also been five silent film versions, and a 1948 Hollywood adaptation starring film noir stalwart Sydney Greenstreet as Count Fosco. Leaving aside the 1997 BBC version, which I consider definitive, my personal favourite is Crimes at the Dark House (1940) starring the great British melodramatic villain Tod Slaughter – Sweeney Todd himself – as Glyde.

The continuing popularity of The Woman in White can largely be ascribed to the dawning of ‘Sensation Fiction’ that it represents, a precursor of the modern mystery and thriller genres and a significant development in the form of the popular English novel. Collins was, said Vanity Fair in 1872, ‘The Novelist who invented Sensation.’ Not that ‘Sensation’ was a label authors sought at the time, it being a pejorative term used by critics who did not share the enthusiasm of Collins’ massive audience. As John Ruskin wrote in his essay ‘Fiction Fair and Foul’, ‘the reactions of moral disease upon itself, and the conditions of languidly monstrous character developed in an atmosphere of low vitality, have become the most valued material of modern fiction.’ ‘Sensation Fiction’ was first given a name in the November 1861 number of the Literary Budget, seeking to define the style of The Woman in White and East Lynne by Ellen ‘Mrs Henry’ Wood. By the following year, the publication of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret cemented the genre.

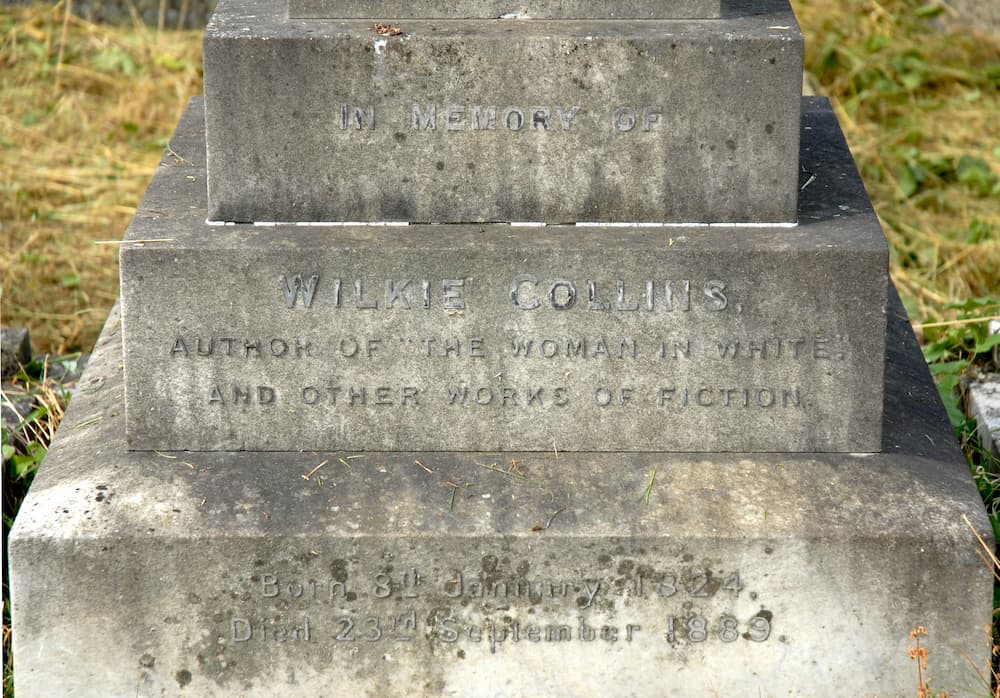

Wilkie Collins’ grave

The ‘Sensation’ novel blended the narrative codes of both realism and romance, literary forms that had previously been quite distinct. It borrowed from the Newgate novels of the 1830s (early crime fiction), melodrama, and gothic fiction, with the horrors of the traditional medieval settings of Radcliffe, Maturin, and Lewis relocated to Victorian England. As Henry James wrote, the sensation novel had ‘introduced those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors’. Therefore, ‘instead of the terrors of “Udolpho” we were treated to the terrors of the cheerful country-house and the busy London lodgings. And there is no doubt that these were infinitely the more terrible.’ Contemporary criminal cases were also a rich source of inspiration, hence Collins’ fragmented narrative, presented like a bundle of legal documents. (In The Moonstone, he would go on to base his great detective Sergeant Cuff on the famous Victorian policeman DI Jack Whicher.) ‘Sensation’ plots commonly featured madness, opium, murder, adultery, bigamy, kidnapping, dark family secrets, and the loss of identity. Because of the modern settings and boundary-pushing narrative edginess, these novels were also able to explore contemporary social issues and anxieties. The Woman in White, for example, is based around the unequal position of married women under English law before the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, all their property automatically passing to husbands who could also lock ‘difficult’ wives away in private asylums with impunity. The changing social dynamics of Victorian Britain are also apparent. Upper-class and aristocrat villains are pitted again middle-class heroes like Walter and Marian, as the industrial bourgeoisie transcend the landed gentry, business and finance creating a new ruling elite. There is also, of course, the fledgling signs of detective fiction in The Woman in White, although the honour of invention must go to Edgar Allan Poe and his C. Auguste Dupin stories in the 1840s. Though Walter and Marian are cast as investigators, with key clues such as the date on a train ticket becoming major plot points, The Woman in White is more ‘mystery’ than ‘detection’, the narrative based more on emotional affect than deductive reasoning. Collins’ masterpiece of detective fiction was to be his 1868 bestseller, The Moonstone.

Although a commercial success and publishing phenomenon, The Woman in White was not much liked by contemporary critics who, like Ruskin, similarly derided his bestselling ‘Sensational’ contemporaries Mary Elizabeth Braddon, J.S. Le Fanu, and Charles Reade. The Archbishop of York denounced the genre from the pulpit, the debate similar in tone to the ‘Newgate Controversy’ of the previous generation, in which ‘criminal romances’ – including Dickens’ Oliver Twist – were decried as socially dangerous. As with the Newgate novelists of the 1830s – W.H. Ainsworth and Edward Bulwer-Lytton – the critical consensus was that Collins had no right to use the kind of subversive and violent material he did without an eye on the moral improvement of his reader, the clause that always saved Dickens from the same charge. The Times review called the novel ‘a mockery, a delusion, and a snare.’ Collins was not happy, announcing ‘Either the public is right and the press is wrong, or the press is right and the public is wrong.’ Time would tell, he decided, concluding that ‘If the public turns out to be right, I shall never trust the press again.’ And so, he didn’t, choosing to measure success in sales over good notices as the reviews became harsher and more condescending.

The 1860s was therefore his decade, comprising his best and most significant work. The Woman in White was followed by No Name in 1862, in which two young women discover after the deaths of their parents that they are illegitimate and therefore penniless; and Armadale (serialised in the Cornhill Magazine between 1864 and 1866), a tale of inter-generational family secrets, murder, doubles, and a compelling flame-haired villainess called Lydia Gwilt, clearly Count Fosco’s female counterpart. In 1868, The Moonstone was published, alongside The Woman in White the novel for which Collins is best known today, and a landmark in British detective fiction. Nine novels were yet to be written, but it is upon this fascinating quartet that Collins’ literary reputation rests. And of all of these, it was The Woman in White of which he was most proud. Upon his death, an envelope left with his solicitor was unsealed, containing clear instructions regarding his epitaph. A plain stone in Kensal Green Cemetery therefore bears the following inscription:

William Wilkie Collins

8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889

Author of The Woman in White and other works of fiction.

For more information on the life and works of Wilkie Collins, visit: The Wilkie Collins Society

Main image: Crimes at the Dark House starring Tod Slaughter and Sylvia Marriott, 1940 Credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Illustration for a poster advertising the stage version that opened at the Olympic Theatre, London, on 9 October 1871. The illustration is by Collins’ friend, the English illustrator Frederick Walker (1840-1875). Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Illustration featured in Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day (1873) with drawings by Frederick Watty and accompanied by biographical pieces on each of the subjects. Credit: Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Gravestone of Wilkie Collins in Kensal Green Cemetery London. Credit: Jeremy Hoare / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article