The Newgate Controversy Part One

Stephen Carver looks at the events that threatened the reputation of the young Charles Dickens

When considering an author as culturally monolithic as Charles Dickens, it’s easy to forget that he wasn’t born the national author, any more than Shakespeare was. As a young journalist in the early-1830s, although already possessed considerable talent and ambition, he was just another freelance writer in the Darwinian world of London publishing. As a court reporter, Dickens covered debates in the Commons as well as following election campaigns around the country and reporting on them for the Morning Chronicle. These travels became the bases for a series of ‘sketches’ of everyday life in several periodicals, written under the pseudonym ‘Boz’. And the rest is history, as they say. John Macrone published Sketches by ‘Boz’ to considerable popular and critical acclaim in 1836, Chapman and Hall offered Dickens the humorous sporting serial that became The Pickwick Papers, another hit; he assumed the editorship of Bentley’s Miscellany and began serialising Oliver Twist, arguably one of the most iconic English novels of the 19th century, multiply adapted for stage and screen. In short, Dickens’ rise was meteoric. Or was it?

By the mid-1830s, Dickens’ star was undoubtedly in ascendance, but since the death of Sir Walter Scott in 1832, no obvious successor to the throne of English letters had yet been crowned, although the smart money was on a colourful historical novelist from Manchester called William Harrison Ainsworth, closely followed by the radical Whig MP Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Both authors were hugely popular in the 1830s and both were conceptually linked through the development of what came to be known among reviewers as the ‘Newgate’ novel. As the term implies, the heroes of these novels were criminals, often lifted from the pages of Newgate Calendars, lurid accounts of crimes, trials and executions named after the infamous prison.

Lytton had originally started writing to support a young family after his aristocratic mother stopped his allowance because she did not approve of his chosen bride, Rosina Doyle Wheeler, the daughter of the Irish feminist Anna Wheeler. His breakthrough novel was Pelham: or The Adventures of a Gentleman (1828), a fashionable or ‘silver fork’ novel about the dandy lifestyle, social climbing and the philosophy of taste which kept readers and reviewers guessing which characters were based on real public figures. Lytton was adept at a variety of popular genres, including historical and gothic romance, and in 1830 published a highly political and redemptive tale of a fictional Georgian highwayman, Paul Clifford. The title character was something an amalgam of several real Newgate calendar villains and the brooding Romantic hero of Friedrich Schiller’s 1781 play The Robbers (Die Räuber), Karl von Moor. In the novel, Clifford is imprisoned as a boy for an offence he did not commit. Inside, he mixes with hardened criminals and emerges into the world apprenticed in crime and ready to use these skills to survive, later explaining, ‘I come into the world friendless and poor – I find a body of laws hostile to the friendless to the poor! To those laws hostile to me, then, I acknowledge hostility in my turn. Between us are the conditions of war’ (Bulwer-Lytton, 1865: 219).

Through his mouthpiece, despite a footnote stating that these sentiments are those of character, not author, Lytton is craftily paraphrasing the political philosopher William Godwin, who in his Enquiry Concerning Political Justice had written that:

The superiority of the rich, being thus unmercifully exercised, must inevitably expose them to reprisals; and the poor man will be induced to regard the state of society as a state of war, an unjust combination, not for protecting every man in his rights and securing to him the means of existence, but for engrossing all its advantages to a few favoured individuals and reserving for the portion of the rest want, dependence and misery (Godwin: 1993, 90).

In a preface to the 1840 edition of Paul Clifford, Lytton confessed that his novel was ‘a loud cry to society to mend the circumstance – to redeem the victim. It is an appeal from Humanity to Law’ (Bulwer-Lytton: 1865, x). A powerful novel in its own day, Paul Clifford is now only remembered, if it is remembered at all, for its opening line, which begins ‘It was a dark and stormy night’, but in moving beyond the picaresque tradition into recent English history and political allegory, spiced up with a bit of melodrama and adventure, Lytton had essentially created the so-called Newgate novel, the modern criminal romance.

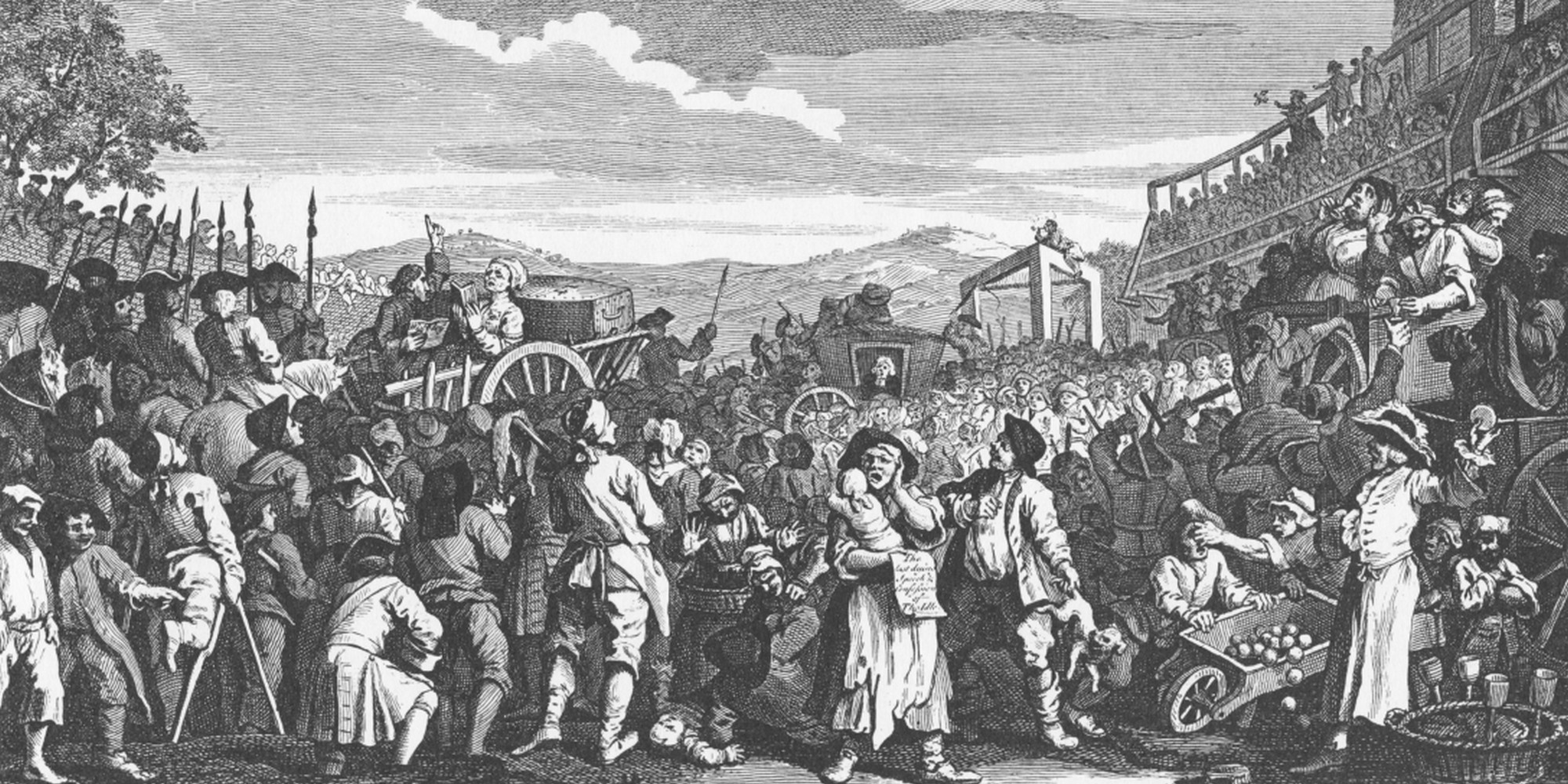

Lytton followed Paul Clifford with another exploration of guilt and the moral conflict between violence and visionary ideals, Eugene Aram (1832), this time based on a real eighteenth-century murderer. The original Eugene Aram was a schoolmaster of humble origins from Yorkshire who had taught himself Hebrew, Latin, Greek, Aramaic and Arabic. In 1744, while Aram was living and working in Knaresborough, a close friend and business associate called Daniel Clarke disappeared after obtaining a considerable quantity of goods on account from local tradesmen. Some of this produce was found on Aram’s property, but there was not enough evidence to link him either with Clarke’s fraud or his disappearance. Nonetheless, Aram thought it prudent to leave Yorkshire (and his wife), and after a stint in London he ended up teaching at King’s Lynn Grammar, where he started writing a book entitled A Comparative Lexicon of the English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Celtic Languages. With his ground-breaking theory of the Indo-European origins of the Celtic languages, Arum could have been a major etymologist, his research pre-dating that of J.C. Pritchard’s Eastern Origin of the Celtic Traditions by decades. Instead, a skeleton believed to be that of Daniel Clarke was unearthed in a cave outside Knaresborough in 1758 and suspicion once again fell on Aram. He was arrested and tried, conducting a spirited defence on his own behalf against the fallibility of circumstantial evidence. Convicted and condemned, Aram finally confessed, his motive being an affair between Clarke and his wife. He was hanged at Knavesmire (‘York’s Tyburn’) on August 16, 1759.

Aram’s duality as a brilliant scholar and homicidal cuckold was a rich source for writers, and in addition to appearing in numerous Newgate calendars (his story ideally fitting the chapbook model of sensational violence and morality tale), he had been the subject of Thomas Hood’s ballad The Dream of Eugene Aram, published in his annual, The Gem, in 1829. In the poem, Aram relates his troubling dream of murder to a schoolboy before his arrest and the revelation that the crime was his own. Hood presents Aram as a tormented, conflicted and guilt-ridden man who is both thoughtful and articulate. The poem was immensely popular and was reprinted in a slim volume of its own by Charles Tilt in 1831, the year before Lytton’s novel was published. Interest in the case was reopened, and the opportunistic Lytton was quick to capitalise. This time there was no call for social reform. Instead, Lytton turned a real killer into a broadly sympathetic protagonist and attempted a deeply psychological character study, making Aram a Faustian seeker after knowledge laid low by poverty and foreshadowing Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, also making use of the codes of gothic romance as had William Godwin in Caleb Williams. As with Paul Clifford, Lytton used footnotes to distance himself from his hero, but whether by accident or design his narrative voice can be read as once more siding with a criminal.

Although Eugene Aram garnered a massive readership, critical opinion was more divided. Regency icons like Harriette Wilson and Pierce Egan loved it, while the Athenæum hailed the book as a work of genius which probably should not have been written, and the Spectator reminded its readers that Bulwer’s novel was closer to Byron’s Manfred than the Newgate Calendars. William Maginn, who Lytton had caricatured in Paul Clifford, unsurprisingly took the most strident view among the voices of disapproval, writing in Fraser’s Magazine, ‘We dislike altogether this awakening sympathy with interesting criminals and wasting sensibilities on the scaffold and the gaol. It is a modern, a depraved, a corrupting taste’. He further suggests, citing copycat murders for profit supposedly inspired by Burke and Hare, that a criminal romance like Eugene Aram may similarly incite violence, because the author ‘little dreams of the lurking demons he may thus arouse’ (Maginn: 1832, 112).

Perhaps paradoxically, the next Newgate novelist was, like Maginn, one of the founding ‘Fraserians’. William Harrison Ainsworth was the son of a Manchester lawyer who had been publishing in Regency journals since the age of sixteen, much-preferring literature to the law, despite his father’s wishes. He had moved to London under the patronage of Charles Lamb in 1825, married and set himself up as a writer, publisher and bookseller after passing the bar. By 1830, he had three books under his belt – a collection of poems, an anthology of essays and short stories, and a historical novel written in collaboration with an old school friend which had caught the attention of Sir Walter Scott, though not for the best of reasons (Scott thought him an ‘imitator’). But despite cutting quite a dash in the small world of literary London, he had yet to make that much of a splash as an author, and with a growing family, he was desperate for money and had begrudgingly returned to legal practice. Writing around the day job, he produced a jaunty gothic adventure entitled Rookwood: A Romance, which was published by Richard Bentley in three volumes in 1834.

Rookwood has a Cain and Abel motif, as two brothers, one legitimate and one not, battle over an inheritance and the same girl against a backdrop of plots, counter-plots, supernatural events, ill-omens and ancient prophecy. There are some similarities to the plot of Scott’s novel Saint Ronan’s Well (1823), and the influences of revenge tragedy and the eighteenth-century gothic novel abound. What makes Rookwood nonetheless unique was the inclusion of the Georgian highwayman Dick Turpin as, along with the rival half-brothers, a point-of-view character. Despite their political differences (like Maginn, Ainsworth was a Tory), the young novelist admired Lytton and had taken a leaf out of his book by fictionalising a notorious criminal. ‘Dauntless Dick’, he later admitted, had also been a hero since boyhood, when his father had thrilled him and his brother with tales of the daring outlaw. Perhaps because of these childhood associations, Ainsworth made explicit what Lytton had been accused of in both Paul Clifford and Eugene Aram, and positively romanticised criminality, writing: ‘Look at a highwayman mounted on his flying steed, with his pistols in his holsters, and his mask upon his face. What can be a more gallant sight? England, sir, has reason to be proud of her highwaymen’ (Ainsworth, Rookwood: 1880, 52). The novel was further enlivened by vivid illustrations by George Cruikshank, the use of ‘Flash’ (underworld slang), a band of gipsy outlaws, and thirty original comic songs and morbid ballads, many of which celebrated illegal behaviour; the most popular, ‘Jerry Juniper’s Chant’, having a chorus that went ‘Nix my dolly pals, fake away’, which meant ‘Never mind, mates, carry on stealing!’

Rookwood was an overnight sensation, catapulting its young author onto the literary A-list and turning the renewed public interest in Georgian outlaws inaugurated by Lytton into a full-on fashionable craze that bridged the social classes. As far as Ainsworth’s massive audience was concerned, Turpin was the hero of Rookwood, to the extent that the section entitled ‘The Ride to York’ that focuses entirely upon him was often republished separately, while many of the Turpin legends (like the famous overnight ride to York to establish an alibi) were actually invented by Ainsworth in the pages of his book, the original Dick Turpin being an extremely nasty piece of work, none too bright and not at all gallant. With Scott two years dead, Lytton making too many political enemies, and Dickens still a journalist, some reviewers dubbed Ainsworth ‘the English Victor Hugo’.

Critical acclaim was virtually unanimous – even Thackeray praised the novel – with only John Forster (destined to become Dickens’ closest friend and biographer), going against the trend in an Examiner editorial, in which he wrote:

Turpin, whom the writer is pleased with loving familiarity to call Dick, is the hero of the tale. Doubtless, we shall soon see Thurtell presented in sublime guise, and the drive to Gad’s Hill described with all pomp and circumstance. There are people who may like this sort of thing, but we are not of that number ¼ The author has, we suspect, been misled by the example and success of ‘Paul Clifford’, but in ‘Paul Clifford’ the thieves and their dialect serve for illustration, while in ‘Rookwood’ the highwayman and his slang are presented as if in themselves they had some claim to admiration (Forster: 1834, 308).

(John Thurtell had murdered the professional gambler William Weare in 1823 and had received a huge amount of press.) But for Ainsworth, there was no such thing as bad publicity, and through the endorsement of Lytton, he gained entrance to the exclusive literary soirees of Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington, joining the cultural elite. On the proceeds of Rookwood, Ainsworth bought Kensal Lodge, a large house on the Harrow Road, and began his own literary salon. One of the people he invited was Charles Dickens. It was through Ainsworth’s famous parties that Dickens really became professionally connected, meeting Forster (whom Ainsworth always considered a friend despite the reviews), Lytton, Thomas Talfourd, Benjamin Disraeli, and the artist Daniel Maclise. Ainsworth also introduced him to John Macrone, the man who would go on to publish Sketches by ‘Boz’, and George Cruikshank, who would illustrate it.

For both Ainsworth and Dickens, the dice were rolling…

Dr Stephen Carver is the author of ‘The 19th Century Underworld’, and ‘The Author Who Outsold Dickens’, both published by Pen & Sword, and which we can recommend highly.

WORKS CITED

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Rookwood, A Romance. Works. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1880. (Original work published 1834).

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. (1865). Paul Clifford. New York: George Routledge and Sons. (Original work published 1830).

Forster, John. (1834). Editorial. Examiner, May 18.

Godwin, William. (1993). Enquiry Concerning Political Justice, London: Penguin. (Original work published 1793).

Maginn, William. (1832). ‘A good Tale badly Told’. Fraser’s Magazine, Vol 5, No 25, February.

Books associated with this article

Barnaby Rudge

Charles Dickens

Nicholas Nickleby

Charles Dickens

The Old Curiosity Shop

Charles Dickens

Oliver Twist

Charles Dickens

Our Mutual Friend

Charles Dickens

The Pickwick Papers

Charles Dickens

A Tale of Two Cities

Charles Dickens

The Mystery of Edwin Drood & Other Stories

Charles Dickens

Great Expectations (Collector’s Edition)

Charles Dickens

Martin Chuzzlewit

Charles Dickens

Little Dorrit

Charles Dickens

Hard Times

Charles Dickens

Bleak House

Charles Dickens

Christmas Books

Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens

Complete Ghost Stories

Charles Dickens

David Copperfield

Charles Dickens

Dombey and Son

Charles Dickens

Great Expectations

Charles Dickens