Book of the Week: Faust

The basic premise of the story of Faust is generally well known. It concerns a magician who agrees to surrender his soul to Mephistopheles, an evil spirit, for a certain period of time in exchange for otherwise unattainable knowledge and magical powers giving him access to all the world’s pleasures. It is believed that the story was based to a large extent on Johann Georg Faust (c1480 or 1466 – c1541), who was a German itinerant alchemist, astrologer and magician. He became the subject of a folk legend, which has been taken up by many writers and composers over the years. The first notable version of his story was Christopher Marlowe’s play The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus (1604).

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, born in Germany in 1749, was a versatile poet, dramatist, novelist, philosopher, statesman, scientist, artist and theatre manager. Considering this list of achievements, it is apparent that he was a man of great intellectual brilliance and energy. His epic drama Faust appeared in 1808. It was his magum opus and completed in stages throughout his life: he began writing it in his youth and the finishing touches to Part Two were made in the year of his death, 1832, the work being published posthumously. Faust is regarded as a closet drama, which means a play to be read rather than acted. It is considered to be one of the greatest works in German literature.

Part One begins like a mystery play with the celebrated prologue in Heaven, essentially a paraphrase of the first part of the ‘Book of Job’ from The Bible. The same bargain is struck in both versions. The Lord gives Mephistopheles permission to test the goodness and integrity of God’s servant, Faust. He is a scholar and alchemist who has fallen into despair because he feels as though he has exhausted the limits of his knowledge and believes that he will only become complete if he can fuse his life with nature and the universe. Mephistopheles makes a bargain with the aged Faust. If in following his desires, he secures one moment of complete contentment he loses his soul. Mephistopheles forces Faust to sign the pact with blood. Faust complains that the demon does not trust his word of honour, but Mephistopheles wins the argument and Faust signs the contract with a drop of his own blood.

In preparation for his trials, Faust is able by magic to regain his youth. And then with Mephistopheles he travels the world enjoying every form of earthly pleasure. He has a love affair with a simple girl, Margaret, whom he betrays. He is also responsible for her death. In response Mephistopheles attempts to capture the soul of Margaret, but the purity of her love for Faust despite his betrayal and her refusal to be rescued from death by Mephistopheles cause her to be saved.

As the first part of the play ends, Faust has yet to achieve his ambitions. In the second part, he is able to taste every form of intellectual and worldly power, but still fails to find the moment of contentment that he desires, even in the love of Helen of Troy, supposedly the most beautiful woman in the world. Mephistopheles is distraught that none of his plans to secure Faust’s soul have worked.

Now a weary old man once again, Faust surprisingly takes an interest in a scheme to reclaim land from the sea, a project which will mean little to him personally, but is able to bring untold good to a great number of people. Here, to his astonishment, in this socially constructive occupation, Faust finds profound happiness. So noble is this altruistic impulse that Mephistopheles is deprived of the soul of Faust who, like the unfortunate Margaret, is redeemed.

Part Two resembles a further exoneration of Faust. He wakes up in a field of fairies in readiness to initiate a new series of adventures and resolutions. Ultimately Faust finds himself in Heaven where angels arrive as messengers of divine mercy to announce to him, and indeed to the reader/audience that, ‘He who strives and lives to strive/Can earn redemption still.’ It seems as though this is Goethe’s final message to the world. The whole work is psychologically enlightening and provides a timeless commentary on the human condition.

Faust has rarely been performed in its entirety on stage. Its difficulties of production are enormous, not to mention the length. However, in 2000, a complete version was performed in Hanover over two days, lasting twenty-one hours in total with intervals. Faust is primarily, a literary-poetic work, which is meant to be read and studied. Nevertheless, on rare occasions, both parts have been performed in carefully truncated adaptations. The first part by itself has received fairly frequent performances and is the basis for of Gounod’s popular opera Faust. There have been several movies based on the work, mainly by German film makers, but these are only abbreviated versions of the original.

One interesting aspect of the Wordsworth edition is that the translator, John Williams, has delved into the early versions of the text and includes a selection of Unpublished Scenarios including scenes for Walpurgis Nacht, the witches’ sabbath, material so ribald and blasphemous that Goethe did not dare publish it.

The legendary figure of the magician and charlatan Faust has not only attracted many poets, but the adjective Faustian has become synonymous for the questing nature of modern Western civilization.

David Stuart Davies

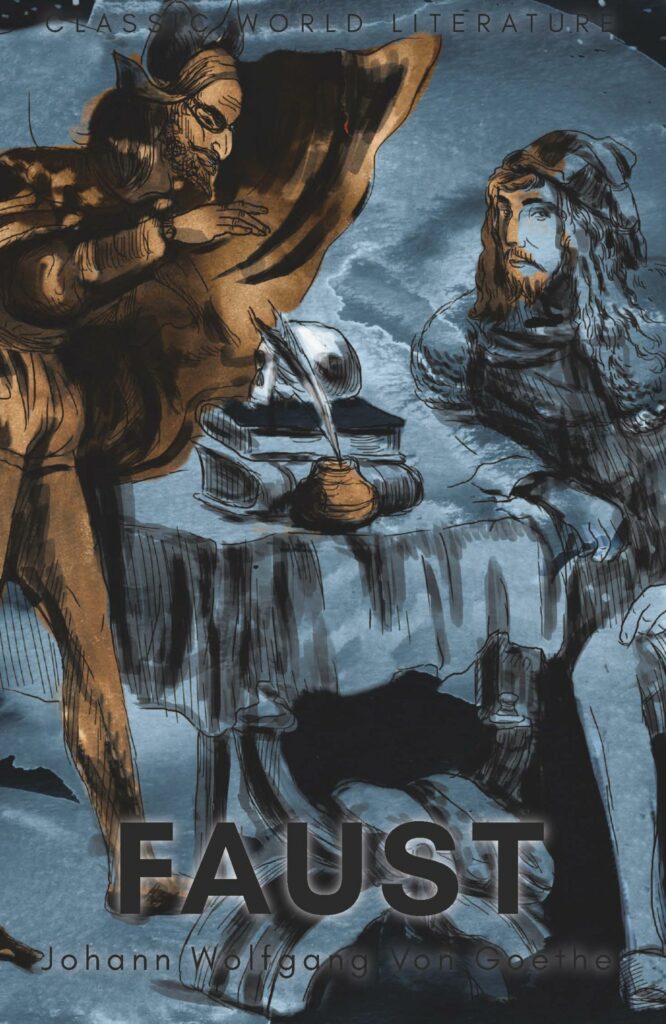

Image: Bronze group of Mephistopheles and Faust outside Auerbachs Keller, Leipzig, Germany, the first stop on their travels. Credit: Agencja Fotograficzna Caro / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article