Filming ‘A Christmas Carol’.

Stephen Carver takes a seasonal look at the many, many adaptations of Charles Dickens’ Christmas classic.

Like James Bond and Doctor Who, everyone has their favourite version of Ebenezer Scrooge, the actor that defines the role for them, probably from whatever version of A Christmas Carol they first saw as a kid. I have seen many polls on social media inviting us to vote for the ‘Best Scrooge’ but they only ever offer three or four choices. This doesn’t even cover all the well-known adaptations of the novella, let alone any of the others. A Christmas Carol is by far the most adapted of Dickens’ works, and one of the most filmed literary texts in history, rivalled only by Romeo and Juliet and MacBeth. At time of writing, in terms of direct adaptations, there have been 23 live action movies and 11 animated versions, with an additional 32 TV productions (24 live action, 8 animated), and 18 parodies. (And that’s leaving aside other media, which includes 25 radio versions, 34 theatrical adaptations – not counting all the Victorian ones – 5 operas, 3 ballets, 2 video games, and 14 audio recordings. Then there’s the derivative works, which are well into three figures.) So, as everyone loves this story, because I love this story, and fresh from a Dickens Fellowship meeting on the original story, I recklessly thought it might be fun to explore some of the different film adaptations and Mr Scrooge’s evolution from page to stage. This is a journey that links Victorian thespian Edward Stirling and Dickens himself to the Muppets and the Captain of the Enterprise. I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that Dickens probably didn’t see any of this coming.

Dickens wrote a series of Christmas books throughout the 1840s, beginning with A Christmas Carol in 1843. He had been inspired by a visit to a ragged school in Saffron Hill in Holborn, the slum district in which he based Oliver Twist. This experience had polarised Dickens’ central social concerns about poverty, crime, industrialisation, and ignorance, already present in his early fiction but now sharply focused after trips to Manchester and the United States had driven home the true horror of rapid industrialisation. As he later put it in the Examiner: ‘Side by side with Crime, Disease, and Misery in England, Ignorance is always brooding, and is always certain to be found.’ Ignorance repeats the cycle of deprivation among the poor, and accounts also for the indifference of the better off in society. Dickens vowed he would strike ‘a sledgehammer blow’ for poor working-class children.

Reginald Owen and Ronald Sinclair in the 1938 MGM film

A Christmas Carol was the result, written quickly in the autumn of 1843 while he was finishing the serial run of Martin Chuzzlewit. There is therefore a certain amount of conceptual crossover, most notably the theme of selfishness in Martin Chuzzlewit, and the way that greed and money leads to a heartless, commercialised society. A Christmas Carol explores the same ground through seasonal fantasy. Sales of the monthly instalments of Martin Chuzzlewit were sluggish, and it was one of Dickens’ least popular novels. His publishers, Chapman & Hall, even threatened to reduce his monthly fee by £50 if sales did not improve. A Christmas Carol, on the other hand, was the bestseller he desperately needed. First published on December 19, 1843, the first edition had sold out completely by Christmas Eve. By the next Christmas, it had already gone through thirteen editions, and it has never gone out of print since its first publication.

Dickens wrote four other ‘Christmas Books’: The Chimes (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846), and The Haunted Man (1848). Although these all sold well on initial publication, they have not stood the test of time like A Christmas Carol, which was always the most popular of the series. That said, it was not the most popular when it came to contemporary theatrical adaptations, although Dickens actively supported Edward Stirling’s A Christmas Carol; or, Past, Present, and Future at the Adelphi. The stage versions of The Chimes and The Cricket on the Hearth did much better, possibly because of the staging difficulties of A Christmas Carol. In the 1840s, special effects were simply not up to the task of producing convincing ghostly visitations. ‘Pepper’s Ghost’, an illusion created by English scientist John Henry Pepper, would not appear until the 1860s, heralding a fashion for paranormal-themed plays. By the end of the decade, Dickens had abandoned Christmas books, being preoccupied with the serialisation of David Copperfield. He did, however, continue to disseminate what he called his ‘Carol Philosophy’ through public readings of A Christmas Carol, which he began in 1853 and continued until his death in 1870. It was not until the advent of film that A Christmas Carol was able to be properly adapted in another medium. A Christmas Carol was, in fact, made for film.

The first film version was made in the UK and released in November 1901. Scrooge, or, Marley’s Ghost had a running time of six minutes, twenty seconds. It was directed by Walter R. Booth, a stage magician and pioneer of British film known for his ‘trick films’, silent single-reelers showcasing innovative special effects. Early cinema made much use of familiar popular narratives so the audiences could follow them easily. Though stagey and static, Booth wowed audiences by superimposing Jacob Marley’s face on a doorknocker, and projecting scenes from Scrooge’s youth onto a black curtain in his bedroom. To condense an 80-page book into six-and-a-half minutes, Booth used Marley’s ghost – an actor draped in a white sheet, not so impressive – to take Scrooge through the various visions, cutting the three Christmas ghosts. Remarkably, the British Film Institute has managed to preserve about half of the film, including the scene in which Scrooge is shown his own grave. And with this, Ebenezer Scrooge entered the 20th century.

The first American film, made by Essanay Studios in Chicago in 1908, is now lost, although the ‘Stories of the Films’ section of The Moving Picture World magazine published just before the film’s release in December gave a scene-by-scene breakdown. A Christmas Carol was 15 minutes long and included the three spirits of Christmas as well as Marley’s ghost. The English-born stage and screen actor Tom Ricketts played Scrooge. Ricketts directed dozens of silent films and was one of Hollywood’s first heavyweight character actors. Other Essanay stars included Francis X. Bushman, Gloria Swanson, and Western star Broncho Billy Anderson.

Edison Studios of New York produced a version that has survived. Released on December 23, 1910, A Christmas Carol was 13 minutes long, into which director J. Searle Dawley managed to cram the visits of the charity committee and Scrooge’s nephew Fred, as well as Marley’s ghost and the three spirits. Australian actor Marc McDermott played Scrooge while Charles S. Ogle was Bob Cratchit. Ogle is best known for his portrayal of the monster in Edison’s Frankenstein, which was also directed by Dawley in 1910.

The next British version was Scrooge (known as Old Scrooge in the US), a more sophisticated 3-reel film with a running time of 40 minutes made in 1913. It even has a framing narrative in which Dickens paces his library in search of inspiration before sitting at his desk to write A Christmas Carol. The film fundamentally covers the events of the original novella. Directed by Leedham Bantock (incidentally the first actor to play Father Christmas on film), Scrooge is notable for starring Seymour Hicks as Scrooge, a role he had been playing on stage since the 19th century. (He also reprised the role in a 1935 British film version. He was knighted the same year.) J.C. Buckstone, on whose play Scrooge, or, Marley’s Ghost had been based, and the son of the great Victorian actor and playwright John Baldwin Buckstone, was also in the cast. Buckstone senior had produced several unlicensed plays based on Dickens’ novels at the Adelphi and the Haymarket and Dickens did not much care for him.

Next, released on Christmas Day 1916, Universal’s The Right to Be Happy is regarded by historians as the first feature length adaptation of A Christmas Carol, though it is only ten minutes longer that Scrooge and is not loyal to the original text. It was directed by Rupert Julian, best known for directing Universal’s 1924 Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney. He also played Scrooge. The rest of the cast were all Universal contract players, who can be spotted in dozens of early classics from the studio. Claire McDowell, for example, who played Mrs. Cratchit was also in The Mark of Zorro (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks and Ben Hur (1925). Emory Johnson, who played Fred, was also in around 20 Essanay Westerns. Universal wanted the film to be more of a morality play that could be shown throughout the year. The script therefore concentrated on Scrooge’s transformation from miser to philanthropist, adding new material about his earlier life, and bizarrely downplaying the Christmas connection. Concerned that Dickens’ original title would yoke the film to the holiday season, studio executives imposed the more generic title. Critics were not buying this, however, and all reviews emphasised the Christmas story. Unfortunately, no prints of The Right to Be Happy have survived.

George C. Scott 1984

Three short adaptations were produced in Britain in the 1920s, two unremarkable silent versions and the first sound production, the nine-minute-long Scrooge (1928), directed by Hugh Croise for British Sound Film Productions, now, unfortunately, lost. The next notable version was Scrooge (1935), starring Seymour Hicks and released by Twickenham Film Studios. This was the first feature-length sound version of the story, with a running time of 78 minutes. Unlike previous film versions, the ghosts rarely appear onscreen. Instead, the novelty of sound led to the creative choice to present them as creepy disembodied voices. Only the Ghost of Christmas Present is shown as a full figure; The Ghost of Christmas Past is a featureless shape, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is depicted only by an outstretched pointing hand, and Marley’s ghost is shown only briefly as the face on the doorknocker. The film has a murky, gothic atmosphere, and it’s a treat to see Hicks acting in sound, recreating his role from the late Victorian stage in the barnstorming style of Henry Irving or Tod Slaughter. It’s still around in the public domain, with a couple of versions on YouTube (look for the 78-minute cut). Because it is in the public domain, there are some very rough DVD copies available. For restored versions, look for the 2002 Image Entertainment DVD release or the 2007 VCI Entertainment version, which bundles a restored version of the 1935 film with the 1951 Renown Pictures adaptation starring Alastair Sim.

Hollywood soon followed with the saccharine A Christmas Carol from MGM (1938), produced by multiple Academy Award winner Joseph L. Mankiewicz, written by Hugo Butler, and directed by Edwin L. Marin. Butler takes several liberties with the source material to make the story less grim and more palatable for family audiences. In his script, Scrooge sacks Bob Cratchit after he accidently knocks his hat off with a snowball outside the office (also docking his last week’s wages to cover damages). The tormented spirits seen outside Scrooge’s window are cut, as is Scrooge’s fiancée Belle, the starving wraiths ‘Ignorance’ and ‘Want’, and Scrooge’s charwoman, laundress, and undertaker selling off his belongings after his death. A romantic subplot is also added involving Fred and Elizabeth (now Fred’s fiancée rather than his wife), the role of both characters greatly expanded. Portly Gene Lockhart, meanwhile, turns Bob Cratchit into a well-fed and jovial figure rather than the victim of food poverty, low wages, and exploitation that Dickens’ intended. (Lockhart later played the judge in the great Christmas movie Miracle on 34th Street.) Veteran British character actor Reginald Owen – who at various times played both Dr. Watson and Sherlock Holmes – was Scrooge. Owen appeared in several iconic movies, including Platinum Blonde, National Velvet, The Picture of Dorian Gray, Kim, and While the City Sleeps, ending his career in Mary Poppins and Bednobs and Broomsticks. Terry Kilburn, an English child actor known for Goodbye, Mr. Chips, Swiss Family Robinson, National Velvet, and Black Beauty was Tiny Tim, while Ann Rutherford – Carreen O’Hara in Gone with the Wind – was a young and pretty Ghost of Christmas Past, eschewing the look of the strange, androgenous creature with the flaming head from the original story. D’Arcy Corrigan, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, can also be seen in Robert Florey’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), and Marley’s ghost was Leo G. Carroll, later Napoleon Solo’s boss in The Man from UNCLE. MGM is still hawking this around as a ‘Christmas Classic’, the original black and white stock now digitally colourised.

But while historically significant, all these movies are just a prelude to the ones we all know and love. After a fallow period following the MGM version, the first of these premiered on November 22, 1951, at the Odeon, Marble Arch.

Scrooge (released as A Christmas Carol in the US) is a powerful adaptation in the tradition of David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948), with a similarly bleak Victorian mise-en-scène, gothic sensibility, and stunning black and white cinematography. The film was directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, a Northern Irish filmmaker who had been mentored by John Ford, once collaborated with Michael Powell, and whose early work included The Tell-Tale Heart (1934). Aside from Scrooge, he is best known for Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1951) and Malta Story (1953). The screenplay was written by Noel Langley, who had written the original screen story for The Wizard of Oz and understood allegorical fantasy. The cast is also an impressive list of postwar British talent. The versatile Scottish actor and popular meme Alastair Sim – a man as comfortable in comedic roles as serious ones – was Scrooge; Ealing regular Mervyn Johns – who starred in the trailblazing British horror film Dead of Night (1945), was an edgy and timid Bob Cratchit; Cockney Sparrow Kathleen Harrison was the Charwoman, now called ‘Mrs. Dilber’ (in the novella, this character was unnamed while the laundress was called Mrs. Dilber); Shakespearean actor and national treasure Michael Hordern was Marley’s Ghost; Patrick Macnee – later ‘John Steed’ – was young Jacob Marley; and Sim’s protégé, George Cole, played the young Ebenezer. Jack Warner, he of Dixon of Dock Green, appeared as ‘Mr. Jorkin’, a role created for the film.

While adhering largely to Dickens’ original story, Langley added a few of his own flourishes that may offend purists, but which add more emotional depth to Scrooge’s character. In The Ghost of Christmas Past episode, the young Scrooge leaves Mr Fezziwig’s employment to work for the ruthless businessman Mr. Jorkin, meeting fellow clerk Jacob Marley. Jorkin ruins Fezziwig, and eventually embezzles so much from the company that his shareholders are on the verge of bankruptcy, and he is on the verge of prison. Scrooge and Marley use their own money to bail out the company in return for controlling shares. In this episode – or, in Dickens’ terms, ‘Stave’ – Scrooge also witnesses the death of his beloved sister Fan in childbirth, and realises he missed her last words asking him to take care of her son, Fred. It is also shown that Scrooge’s mother died giving birth to him, causing his father to resent him and send him away to school. In the original novella, Fan is much younger than Ebenezer, and her cause of death is not mentioned. In the movie, Ebenezer is younger than Fan. Her death causes him to resent his nephew as his father did him. This plotline subsequently turns up in other adaptations. Finally, ‘Belle’, Scrooge’s fiancée in the novella becomes ‘Alice’, and is given an extra scene in the Ghost of Christmas Present episode, when she is shown working at a homeless shelter, a device later used in Bill Murray’s Scrooged (1988). Unlike the original Belle, Alice is not depicted as being happily married.

Bill Murray ‘Scrooged’ 1988

Scrooge was a commercial success in the UK, Sim and Dickens both greatly loved, but a box office disappointment in America. Contemporary critical notices were also mixed at best, Variety, for example, dismissing the film as ‘a grim thing that will give tender-aged kiddies viewing it the screaming-meemies,’ while ‘adults will find it long, dull and greatly overdone.’ It was, however, a grower, finding its place in seasonal television re-runs for decades to come, Sim’s portrayal of Scrooge for many viewers – including yours truly – being judged as definitive. Richard L. Coe of The Washington Post summed it up: ‘This may not be A Christmas Carol of recent tradition, but I’ve an idea it’s the way Dickens would have wanted it. It’s the way he wrote it.’ Patrick Macnee agreed, often citing the film as his favourite version of the story, because ‘it really seems to capture the true essence of the Dickens novel.’ Because of the Victorian setting, the age of the film seems to convey authenticity. Like David Lean, Hurst understood the connection between Dickens’ London and the postwar city, still pock-marked with bomb craters, its population skint, and half-starved with rationing. Sim’s haunted Ebenezer Scrooge therefore endures, the world of Dickens made for the larger-than-life character actor and comic genius. After fifty years of A Christmas Carol on film, this is the first true benchmark.

Such was the power of the 1951 version that filmmakers did not touch A Christmas Carol for a generation. The trigger for a new version was the success of Carol Reed’s 1968 film version of Lionel Bart’s stage musical Oliver! This led to Scrooge (1970), an original film musical directed by distinguished British producer, director, cinematographer, and screenwriter, Ronald Neame, the producer of David Lean’s Great Expectations and Oliver Twist. The film starred Albert Finney as Scrooge, Alec Guinness as Jacob Marley, Edith Evans as the Ghost of Christmas Past, and Kenneth More as the Ghost of Christmas Present; Paddy Stone was the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, and David Collings was Bob Cratchit. (Stone was a stage musical veteran while Collings was a familiar face from television, appearing in shows such as Dangerman, Doctor Who, Blake’s 7, and Sapphire & Steel.) Songs and book were written by Leslie Bricusse, a British composer, songwriter, and playwright best known for Doctor Dolittle, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and Gene Wilder’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. (He also wrote the theme songs for Goldfinger and You Only Live Twice.) Scrooge is built around eleven musical arrangements, with songs such as ‘Father Christmas’, ‘See the Phantoms’, ‘I Like Life’, ‘I’ll Begin Again’, and my personal favourite, ‘I Hate People’.

The film was shot at Shepperton Studios using many of the sets from Oliver! and looks beautiful as a costume drama. The credits sequence is also impressive, featuring a series of illustrations by Ronald Searle mirroring Victorian illustrators like John Leech and George Cruikshank. Though the story keeps to Dickens’ main plot points, it does take a few liberties. The action is moved to 1860, ‘Fred’ becomes ‘Harry’, Scrooge’s lost love is now Fezziwig’s daughter, ‘Isobel’, The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come drops Scrooge into Hell to be the devil’s clerk, and in his rebirth scene he dresses as Father Christmas and distributes presents all over London. Finney is a good Scrooge and Guinness steals the film as Marley. If you like musicals, this is well worth checking out. The songs aren’t as memorable as those of Oliver! and you’ll probably forget them as soon as the film’s over but they’re catchy enough. Scrooge later did an Oliver! in reverse and was converted to a stage musical in 1992 starring Bricusse’s longtime creative partner Anthony Newley. It was revived in 2003, 2004, and 2013 with Tommy Steele as Scrooge, and last year an animated version was released by Netflix directed by Stephen Donnelly with Welsh actor and singer Luke Evans voicing Scrooge.

Nothing happens in the cinema after this until Bill Murray’s Scrooged in 1988, but before I get to that I’m going to cheat and mention a TV film which has entered the public consciousness as one of the classics. A Christmas Carol was a US/UK coproduction, made-for-television feature length movie broadcast on CBS in America and released theatrically over here in mid-December 1984. It was directed by the darling of the British New Wave, Clive Donner (The Caretaker, Nothing but the Best, What’s New Pussycat?, Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush), who had been an editor on Hurst’s 1951 Scrooge. The script was by the American TV writer Roger O. Hirson. The cast is amazing: George C. Scott as Scrooge; Frank Finlay (Marley’s Ghost); Angela Pleasence (Spirit of Christmas Past); Edward Woodward (Spirit of Christmas Present); David Warner (Bob Cratchit); Susannah York (Mrs. Cratchit); Joanne Whalley (Fan); Liz Smith (Mrs. Dilber); and Michael Gough (Mr Poole, one of the charity workers). Nigel Davenport also appears as Scrooge’s father. The film was shot in the historic medieval county town of Shrewsbury, and the Victorian ‘look’ is impeccable, comparable to the kind of costume drama the BBC were making at this point.

Roger O. Hirson was a journeyman Television writer who once almost won a Tony, and he wisely kept as close to his source material as possible, making this one of the most loyal adaptations of the novella. Borrowing from the 1951 film, Scrooge’s mother died giving birth to him, causing his father to resent him, shipping him off first to boarding school then as an apprentice to Fezziwig. Academy Award winner George C. Scott was a superb Scrooge, playing him as a ruthless and cynical businessman with a dark sense of humour who at first defends his position to the spirits. Scott was also doing some great horror in this period. He had starred in The Changeling in 1980, an atmospheric old school ghost story that had done rather well, and the producers played up the connection with the tagline: ‘A new powerful presentation of the most loved ghost story of all time!’ He was also fresh from Stephen King’s Firestarter (1984) and would go on to star as C. Auguste Dupin in Jeannot Szwarc’s Murders in the Rue Morgue (1986) for CBS and William Peter Blatty’s underrated Exorcist III (1990). Scott was nominated for an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor for his portrayal of Scrooge, and for many viewers he vies with Alastair Sim for the title of ‘Best Scrooge’.

Michael Caine and Kermit the Frog 1992

And so, to Scrooged (1988), the Saturday Night Live version of A Christmas Carol. 145 years after the original novella, somebody finally decided to do something different with the material. Scrooged is dark, anarchic, intelligent, and a savage satire of the entertainment industry and media culture that seems to get more relevant every year. Ebenezer Scrooge is updated to Frank Cross, a ruthless, narcissistic, and tyrannical television executive charged with winning the Christmas ratings war with a cheesy musical version of A Christmas Carol called Scrooge, a film within a film that is just as tacky as it sounds. Bob Cratchit becomes Frank’s long-suffering PA Grace (played with dignified pathos and dry wit by Alfre Woodard), and ‘Belle’, the one that got away, is hippy ex-girlfriend Claire (Karen Allen), who now works with the homeless. Tiny Tim is Grace’s son, Calvin (Nicholas Phillips), who has been mute since his dad was murdered, and Marley becomes Lew Hayward (John Forsythe), Frank’s hard drinking mentor who died of a heart attack playing golf seven years before. Veteran actor John Houseman also appears as himself narrating Scrooge, who Frank describes as, ‘America’s favourite old fart, in front of a fire, reading a book.’ The action is updated to contemporary New York, with some great turns by Carol Kane as the Ghost of Christmas Present, a kind of goth fairy with a penchant for violence, and David Johansen of the New York Dolls as the Ghost of Christmas Past. (The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a scary animatronic.) The script was written by SNL stalwarts Mitch Glazer and Michael O’Donoghue, with Murray interfering and ad libbing as the film went along. The film’s climax, for example, when Frank is redeemed on live TV, was almost entirely improvised by Murray.

This was Murray’s first film since Ghostbusters, which producers namedropped shamelessly in the advertising. It was initially not a great success, being deemed ‘too dark’ by many critics, Roger Ebert, for example, calling it one of the most ‘disquieting, unsettling films to come along in quite some time,’ arguing that it was more about pain and anger than comedy. Others only liked the dark side and criticised the sentimentality of the Third Act. Nonetheless, Scrooged eventually broke $100 Million, and it has since become a cult favourite and a Christmas classic, joining the best of them on television every holiday season. In 2017, Collider.com named Scrooged the fifth-best adaptation of A Christmas Carol, using ‘a classic tale of redemption as the framework for a satire of modern culture’s desire to embrace the irredeemable.’ Scrooged was ahead of its time. Unfortunately, we are now catching up in reality. It might be a bit scary and adult for the kids, but Scrooged remains a great Christmas movie, particularly for people who don’t like Christmas movies.

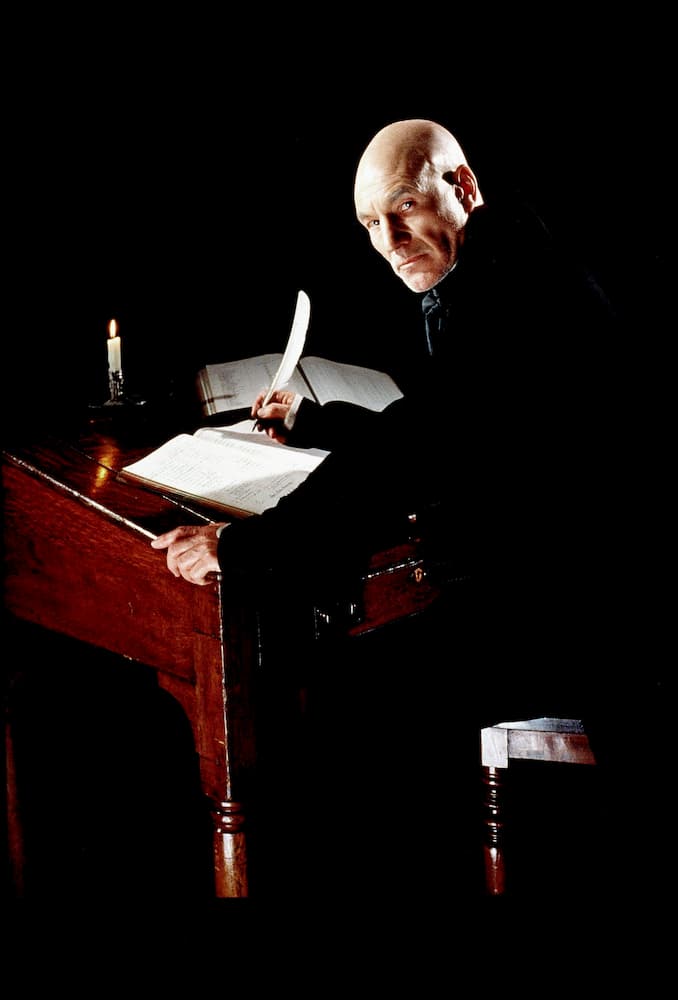

The year before Scrooged, 1987, saw a one-man stage production of A Christmas Carol adapted by Patrick Stewart, performed once at the parish church of his hometown, Mirfield, West Yorkshire, in support of their church organ restoration. The play was three-and-a-half hours long; there were no costumes or props, and Stewart played over 30 characters. Later, during the second seasons of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Stewart streamlined the play into a tight one-man show which he performed at Christmas for several years in the US and the UK in the late 80s and early 90s, winning the 1992 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding One-Person Show and the 1994 Laurence Olivier Award for Best Entertainment. More on Patrick Stewart later…

Scrooged clearly shook something loose, as the next adaptation was The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992), destined to become another cult favourite. The film was directed by Brian Henson (the son of Muppet creator Jim Henson, who had tragically died of pneumonia in 1990), and penned by The Muppet Show writer Jerry Juhl. The film is another musical, comprised of 14 songs by Paul Williams with a score by Miles Goodman. George Carlin, David Hemmings, Ron Moody, and David Warner were all considered for the part of Scrooge, which Henson eventually offered to Michael Caine, who told him: ‘I’m going to play this movie like I’m working with the Royal Shakespeare Company. I will never wink; I will never do anything Muppety. I am going to play Scrooge as if it is an utterly dramatic role and there are no puppets around me.’ And so, he did, which is the genius of his performance. Though he gives us a couple of songs, Caine plays it completely straight, making one wonder how great a serious version of the Carol would have been had he done that instead. Oddly, this implacable foil works perfectly with the Muppets, ably supported by British actor Steven Mackintosh as Fred. The humour comes from the rigidity of Caine’s performance; like Adam West in Batman, there is all this crazy, colourful stuff going on around him that he apparently either doesn’t see or accepts as completely normal.

Patrick Stewart 1999

The other major roles are all taken by Muppets. Kermit the Frog is Bob Cratchit, Miss Piggy is Mrs Cratchit, and Robin the Frog is Tiny Tim. Marley becomes ‘Marley and Marley’ (who get the best song), played by Statler and Waldorf, Fozzie Bear is ‘Fozziwig’ (what else?), Dr Bunsen Honeydew and Beaker are the charity collectors, Sam Eagl is Young Ebenezer’s schoolmaster, and The Great Gonzo is Charles Dickens. Well, he’s not exactly Charles Dickens, as his companion Rizzo the Rat keep gleefully pointing out, but he is the narrator, and he knows what’s going on, though this often involves breaking into places to witness story events. This gives us another one of those ‘story-within-a-story’ devices like the Scrooge holiday special in Scrooged and provides a lot of the humour while the original story unfolds, largely as it should.

This one is a real guilty pleasure. The songs are as catchy as hell, Caine is an excellent Scrooge, and Gonzo as Dickens is a subversive delight. Of all the Muppet movies, this one is undoubtedly the strongest. It is also a very good way to introduce children to Dickens, and I defy you not to tear up as ‘God bless us, everyone.’ At the end of the day, this is still A Christmas Carol. Just as I love the Alaister Sim version, The Muppet Christmas Carol is my dear wife’s favourite, and both movies are wheeled out and inflicted on the family every Christmas. This year, The Muppet Christmas Carol’s getting a limited release in cinemas, so we get to see it on the big screen on Christmas Eve. If you have young kids, you might want to consider taking them to see it too. I expect the experience is quite magical.

Following the Muppets, in 1999 Patrick Stewart returned as Scrooge in another popular contender for everyone’s favourite version of the story. I’m cheating again, as this one’s a TV movie, but it’s too significant to reject on a technicality. Patrick Stewart is always on the social media polls for the ‘Best Scrooge’, and quite rightly so. A Christmas Carol (1999) is a UK/US coproduction for Turner Network Television (TNT) and Hallmark Entertainment. Because of his one-man show, Stewart was an obvious choice for the starring role. (His literary skills were in full swing too, having played Ahab in the Hallmark/America Zoetrope TV adaptation of Moby Dick the previous year.) The screenplay was written by Peter Barnes, best known for his 1968 play The Ruling Class and an experienced literary adapter; the film was directed by David Hugh Jones, a British stage, television, and film director who started his career with the Royal Shakespeare Company. There is thus something quite theatrical about this version, almost like an open-air production, enhanced by the use of historical and derelict buildings as sets, with heavyweight British character actors like Stewart and Richard E. Grant as Bob Cratchit, Saskia Reeves (Mrs Cratchit), Dominic West (Fred), Celia Imrie (‘Mrs. Bennett’, one of Fred’s Christmas guests), and Liz Smith as Mrs. Dilber (again). There is also an effortlessly sinister turn by Joel Grey as the Ghost of Christmas Past; although the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come attempts to replicate John Leech’s original illustrations but ends up looking quite pantomimic. With glowing red eyes, let’s just say, it has not aged well. In addition to the original text, this adaptation takes as its inspiration the 1951 film version, in its gothic tone and use of bleak locations and set designs. Alongside the 1984 version, this is the strongest of the TV movies, although very different in style. It also represents the end of a rich and fascinating cycle of adaptations that begins in 1951. Most of the actors popularly identified with Ebenezer Scrooge inhabit this period.

There is, however, one more Scrooge we must mention. I’ve avoided the animated movies for the sake of space, but this one deserves to be in the Christmas Carol film pantheon. Robert Zemeckis’ A Christmas Carol (2009) is also a motion capture animation, a process of recording the actions of human actors and using that information to animate digital character models in 2D or 3D computer animation, so there is live action in there somewhere. (Other films using this technique include The Polar Express, Monster House, and Beowulf.) This is the third Disney version of A Christmas Carol, following Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983) – which is exactly what it sounds like – and The Muppet Christmas Carol. The film was written and directed by Academy Award winner Zemeckis, who is probably best known for the Back to the Future trilogy, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and Forrest Gump, for which he won the Oscar. He has described the original A Christmas Carol as one of his favourite stories about time travel. It stars Jim Carrey as Scrooge, who also plays the three Christmas spirits; Gary Oldman as Bob Cratchit, Jacob Marley, and, weirdly, Tiny Tim; Colin Firth as Fred; and Bob Hoskins as Mr Fezziwig and ‘Old Joe’, the fence who buys the dead Scrooge’s belongings. Robin Wright plays Fan and Belle.

Robert Zemeckis’ A Christmas Carol (2009)

Again, like the 1999 Patrick Stewart film, there is a definite feel of the 1951 version about this one, with the accent of Carrey’s Scrooge not a million miles from Alastair Sim’s resonant Edinburgh baritone. (He makes the Ghost of Christmas Past Irish and gives the Ghost of Christmas Present a Yorkshire accent.) Stylistically, the film feels like an updated version of John Leech’s original illustrations against a dark, hyper-real reimagining of early Victorian London. The set pieces are lavish, but look like a video game, but the interiors are claustrophobic and threatening. By design, the script stays close to the original novella, especially the dialogue, making this another one of the most loyal adaptations. If there is a downside, it is the ‘uncanny valley’ factor when relating to the characters. They look like the actors, but they don’t. They look like Dickensian illustrations come to life, but they’re not traditionally animated; they are, simply put, too real. Japanese Professor of Robotics Masahiro Mori first introduced the concept of the ‘uncanny valley’. He theorized in 1970 that as the appearance of a robot is made more human, our initial response will be positive and empathetic, but after a certain point this changes to a strong revulsion. I watched Zemeckis’ A Christmas Carol again recently and I still have mixed feelings. It is a wonderfully acted, visually stunning piece of work, but there’s still something eerie about it that the ‘rebirth’ ending, and all the laughter and merrymaking don’t quite disperse. As Mary Elizabeth Williams of Salon.com wrote, the film ‘is a triumph of something—but it’s certainly not the Christmas spirit.’ After a century of costume dramas, however, it is, at least, different, yet at the same time I would have loved to see a live action version starring actors of the calibre of Carrey and Oldman.

And this, I think, brings us almost up to date, though an honourable mention must go to BBC Films 2018 stage-to-film adaptation of a one-man performance by Simon Callow, based on his stage recreation of Dickens’ own performance adaptation, which brings us full circle.

I’m aware here that I’ve only scratched the surface. There are so many other versions of the Carol worth seeking out, which I don’t have time or space to cover, such as the 1969 ITV Carry on Christmas show with Sid James as Scrooge, or Bah, Humduck! A Looney Tunes Christmas (2006) with Daffy Duck as Scrooge; A Christmas Carol: The Musical (2004), starring Kelsey Grammer, in which Scrooge meets the ghosts before and after Christmas, rather like Dorothy’s companions in The Wizard of Oz; Steven Knight’s 2019 reimagining for the BBC; the sublime Blackadder’s Christmas Carol (1988), or the 1947 live DuMont television version starring horror icon John Carradine as Scrooge… the list really is almost endless. And they show no sign of stopping. Most recently, in addition to the 2022 Netflix remake of the 1970 musical, there is Spirited (also 2022), a musical comedy and modern retelling of A Christmas Carol directed by Sean Anders, starring Will Ferrell and Ryan Reynolds. This is apparently a satire of the other adaptations of A Christmas Carol, although I have yet to see it so can offer no opinion.

I like to cycle around the different versions of A Christmas Carol every Christmas, and this post is in many ways intended to inform those of you who do the same. This year, so far, I have watched the Patrick Stewart and Jim Carrey versions, and the family have our tickets for The Muppet Christmas Carol at the VUE on Christmas Eve, which I must confess I’m really looking forward to. That said, whenever I see an online poll, I always vote for Alastair Sim.

Happy Christmas, anyway, and in the immortal words of Tiny Tim, ‘God bless Us, Every One!’

For more information on the life and works of Charles Dickens, visit The Dickens Society

Main image: SCROOGE, (aka A CHRISTMAS CAROL), Alastair Sim and Michael Hordern in Scrooge (1951). Credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Publicity still from A Christmas Carol featuring Reginald Owen and Ronald Sinclair MGM 1938 Credit: PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: A Christmas Carol , George C. Scott, 1984, TM and Copyright © 20th Century Fox Film Corp. Credit: Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Poster for Scrooged, the 1988 Paramount film with Bill Murray. Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Michael Caine as Scrooge in The Muppet Christmas Carol 1998, directed by Brian Henson. Credit: Entertainment Pictures / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: Patrick Stewart in A Christmas Carol (1999). Credit: Copyright Hallmark Entertainment / Cinematic / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 6 above: A Christmas Carol (2009) directed by Robert Zemeckis. Credit: Moviestore Collection Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article

A Christmas Carol (Collector’s Edition)

Charles Dickens

A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens