Ford Madox Ford, Brexit and Trump

On Ford’s birthday, Sara Haslam considers how he might have viewed the momentous events of 2016

My first experience of Ford Madox Ford’s fiction was as an undergraduate in Liverpool, in a course on twentieth-century literature. It was still unusual to find his work on university syllabuses, but Parade’s End was on mine. I was immediately gripped by its account of the First World War (as the marked-up edition I still use shows – it’s dated December, ’90, which, in turn, dates me), and knew I wanted to find out more about this writer. When, soon after, I got the opportunity, I explored his work as emblematic of various kinds of fragmentation, with particular reference to psychology, and ideas around modernism, as well as the war. Since then, my interest has broadened, in a way that’s in keeping with a writer like Ford who had many distinct phases in his career, in terms of style, content and geography. Ford enjoyed pan-European influences and experiences and made the first of many trips to America in 1906.

As a British reader and enthusiast of Ford’s work, it seems impossible to contemplate marking his birthday this year without reference to Brexit and the US presidential election. These events (and other votes across mainland Europe) provide the lens through which I celebrate Ford’s life and literary output today.

Ford was born Ford Hermann Hueffer on 17th December 1873, in Merton, Surrey. His father Franz was a German immigrant who became a music critic for The Times, while his mother, Catherine, was a painter, and Ford Madox Brown’s younger daughter. Soon after he was born, Ford’s maternal aunt Lucy married the writer William Michael Rossetti, brother of the poet/painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Ford’s familial networks linked him at once to the Pre-Raphaelite painters, musicians of the day, and the Rossetti clan – Christina Rossetti’s poetry became a particular inspiration. The artistic inheritance that was his at birth, therefore, was rich, and clearly deeply embedded. By his early twenties, Ford would display talent as a composer, poet, and prose writer, publishing fairy tales and a biography of his famous grandfather (Madox Brown). But 1873 was also the year of the biggest economic crisis the industrialised world had yet seen. The creative life was not, perhaps, the most pragmatic of career choices. Nonetheless, it was the one he made (and the one forcibly recommended by an irascible as well as beloved Madox Brown). Ford never really tried to get a job. And though he moved into the twentieth century an innovator and keenly modern technician of poetry and fiction he never experienced proper financial security across his 66 years: the Wall Street Crash put an end to the temporary fame and fortune that finally came to him in New York in the 1920s. This seems amazing considering his work ethic.

As well as the classic texts for which he is famous, the Fifth Queen trilogy (1906-8), The Good Soldier (1915) and Parade’s End (1924-28), Ford published over 70 titles in his lifetime, in multiple genres. His output was secondary, if anything, to his belief in active contribution to a broad and inclusive literary culture. He edited two magazines, the earlier of which, the English Review, changed his native literary scene, while the transatlantic review brokered from its base in Paris a creative and critical conversation between avant-garde artists in Europe and the United States. From the first years of his career to its last days, he mentored writers in London, Paris and New York who would themselves go on to produce some of the best-known poetry and fiction of the twentieth century. Ezra Pound was one of them, and he never forgot the debt he owed Ford. (Pound’s obituary, published in August 1939, called Ford a ‘gallant combatant’ for ‘things of the mind’, stressed his generosity of spirit and brilliance as an editor, and described him, two weeks before his death, still engaged in the ‘fight for free letters’ in New York.)

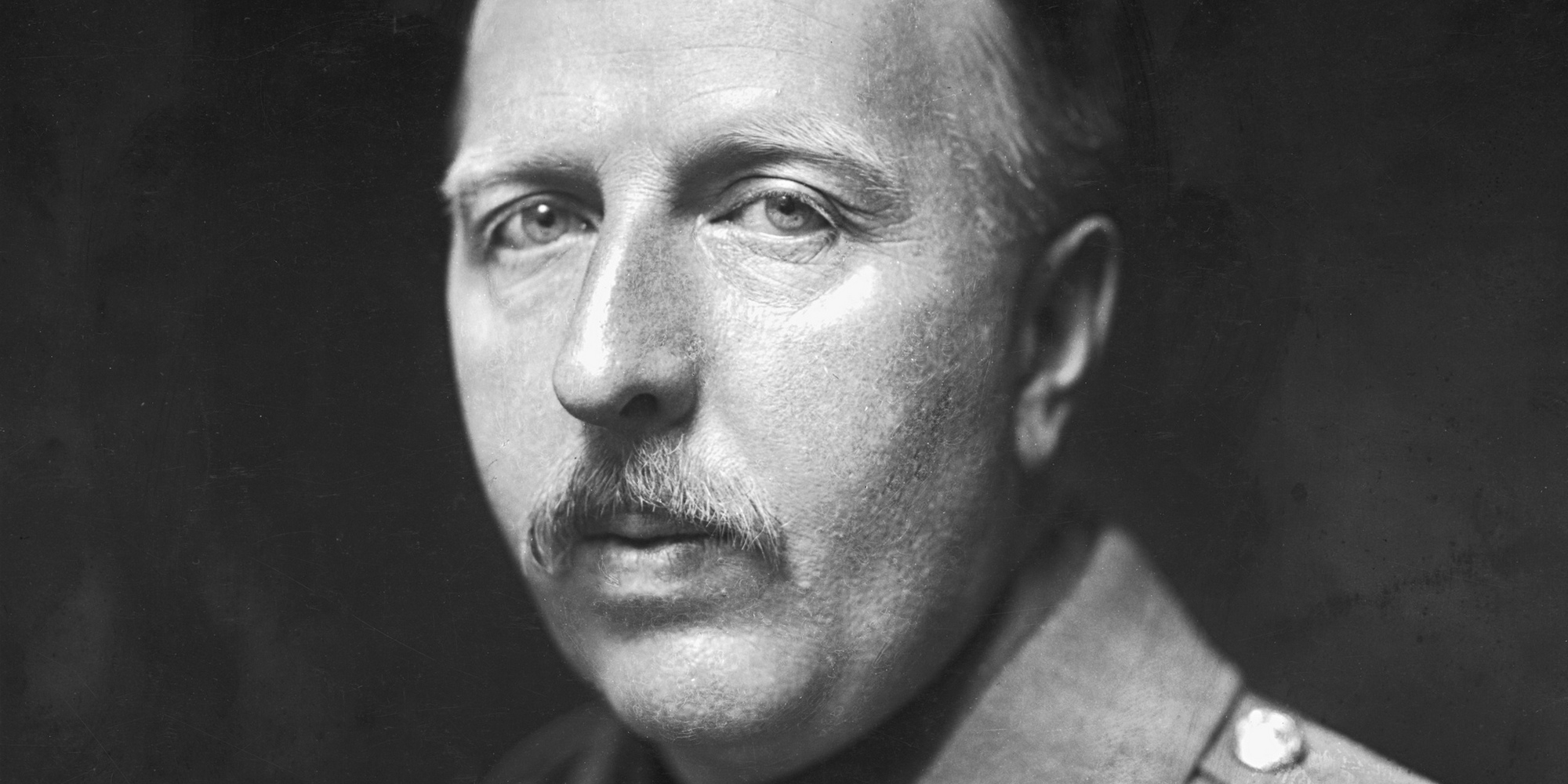

Ford’s schooling was less bohemian than his home life, which included a period of living with his grandfather after his father’s sudden death in 1889, but at Pretoria House, there was a focus on languages and culture that also helped to shape his creative and intellectual life. He emerged from school trilingual, and able to explore his father’s German heritage and appreciate the French influences on his grandfather’s work. It wasn’t long before he found his own such influences in Maupassant and Flaubert. Ford kept the name Hueffer until 1919 – one proof of the psycho-political turmoil the First World War provoked in him, especially as he joined the Welch Regiment in 1915. When the war first broke out, he said he refused to believe the press write-ups of German atrocities.

Building on his early experiences, Ford’s later life and career were triangulated between the UK, France, and America. He wrote about France and America, as well as England, repeatedly, in fiction, journalism, poetry, and memoir. And in a turn that his signature impressionist style would thus have been uniquely suited to exploiting, neither the outcome of Brexit nor the American election is, as I write, absolutely certain. Hillary Clinton’s share of the popular vote means there are two different results being debated in North America. ‘History’ is having to wait for the momentousness to show itself, and one can imagine this writer, who was fascinated by ‘creative history’ and its emphasis on empathy and comprehension, weighing into that gap time and again. Brexit, on the other hand, requires so many lawyers to undo and refashion so many laws that it’s hard to imagine it actually happening, especially as the most essential legal experts are those the political drift has marginalised. Rarely has the Dickensian circumlocution office found a more accurate modern analogy. Ian Jack recently channelled Christopher Clark’s history of the First World War (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/26/human-factor-gave-us-brexit-trump) to express another resonance of chaos: ‘policy oscillations and mixed signalling’ mean that mainland Europe, in 2016 as in 1914, possesses little clue about what we in the UK actually want. In 1914, Ford did not know what he wanted either. His father was a German immigrant and he was a literary cosmopolitan. ‘Whichever side wins’, Ford wrote after war broke out, ‘my heart is certain to be mangled in either case’.

Ford travelled in Germany in his teens and twenties to meet relatives, explore Catholicism (his first two daughters were received into the church on one trip), and, like many other health tourists of his class and time, to take cures for the nervous illness and agoraphobia from which he suffered seriously at times. (He also went there to look for a divorce from his wife Elsie Martindale, whom he had married in 1894, but never found it.) In the end, he joined the war effort to fight against what he termed ‘Prussian militarism’, and wrote officially commissioned propaganda. But, like Lord Haldane, for example, who was finally ousted from his cabinet position by the Northcliffe press because of the way his politics were both nuanced, and challenged, by his broader vision, Ford’s heart was certainly ‘mangled’ even as he fought. And, after all the suffering he saw and experienced, with Parade’s End, he broke his cardinal rule of not writing with a moral purpose because he wanted it both to provide the bigger picture and to help avoid future wars.

Ford never lived in Germany. After he left England for good in 1922 it was for France, and there he remained until his death in Deauville in June 1939, apart from the sometimes lengthy periods in which he lived and worked in the United States. Ford’s partner Stella Bowen, the Australian painter, went with him in 1922, as did their daughter Julie. He met the last love of his life, Janice Biala, a Polish immigrant to New York who was also a painter, in that city in 1930. He was a happy emigrant. He found the distance between him and England was a creative one, a productive one, and, although he didn’t know it when he first left, necessary before he could write his post-war masterpiece, Parade’s End.

So how would Ford have voted this year?

Well, if he had decided to come ‘home’ to vote, the man Gertrude Stein called ‘all European, all experience’, would almost certainly have elected to remain rather than to leave – though like his grandfather before him he did not like institutions (in Ford Madox Brown’s case, the Royal Academy), or complex legislation. If he’d managed to qualify to vote in the US, as a pro-suffragist polemicist he might well have voted for the first woman President, and yet his natural enthusiasm was for rural ‘souths’ against urban ‘norths’.

Really, though, it’s not important (while being, of course, anachronistic) to think too hard about how Ford would have voted. For this reader at least, the take-home point is that his life’s work was an aesthetics of expansiveness, curiosity, and of empathy. As a craftsman, editor, and mentor Ford offered a warm welcome to all those who had an interest in the ‘Republic of Letters’. The concept of walls was anathema, and the Channel, well, it was just something that had to be crossed to continue the artistic conversation that was life to him. ‘One day – may it come soon – [he wrote in 1927] there will not be any America, there will not be any Europe, there will just be the World’.

Happy birthday Ford!

The smaller images are courtesy of the Ford Madox Ford Collection, #4605, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Readers who are interested to know more of the life and works of Ford Madox Ford should visit the website of the Ford Madox Ford Society at fordmadoxfordsociety.org

Books associated with this article