Stephen Carver looks at Henry Mayhew

THE REAL HENRY MAYHEW PART ONE: Traveller in the Poor Man’s Country.

As the freelance journalist is never off the clock, William Thackeray was, like a friend and rival Charles Dickens, a born people watcher. In a short piece for Punch entitled ‘Waiting at the Station’ written in March 1850, Thackeray thus turns the everyday experience of killing time at Fenchurch Street into an essay on the unknowable gulf between the working class and his own, notionally inspired by a group of obviously poor women who are emigrating to South Australia:

But what I note, what I marvel at, what I acknowledge, what I am ashamed of, what is contrary to Christian morals, manly modesty and honesty, and to the national well-being, is that there should be that immense social distinction between the well-dressed classes (as, if you will permit me, we will call ourselves) and our brethren and sisters in the fustian jackets and patterns.

But this isn’t just wool-gathering. Thackeray is, in fact, responding to an explosive series of articles about the London poor in The Times’ main competitor:

What a confession it is that we have all of us been obliged to make! A clever and earnest-minded writer gets a commission from the Morning Chronicle newspaper, and reports upon the state of our poor in London: he goes amongst labouring people and poor of all kinds – and brings back what? A picture of human life so wonderful, so awful, so piteous and pathetic, so exciting and terrible, that readers of romances own they never read anything like it; and that the griefs, struggles, strange adventures here depicted exceed anything that any of us could imagine … But of such wondrous and complicated misery as this you confess you had no idea? No. How should you? – you and I – we are of the upper classes; we have hitherto had no community with the poor (Thackeray: 1850, 92).

Feigning complete ignorance of the plight of the urban poor is a bit of a reach, however – as is describing himself as ‘upper class’ – albeit a good ‘hook’ for the article. Dickens had by then been writing about the subject for well over a decade and, as his commercial nemesis G.W.M. Reynolds wrote in The Mysteries of London, ‘The most unbounded wealth is the neighbour of the most hideous poverty; the most gorgeous pomp is placed in strong relief by the most deplorable squalor; the most seducing luxury is only separated by a narrow wall from the most appalling misery’ (Reynolds: 1848, 3). Similarly, the middle-class reading public was well aware of the reports of Kay Shuttleworth and Edwin Chadwick, although Thackeray is citing something much more vivid than the standard tone of early-Victorian social investigation.

Instead, what Thackeray is really noting is an ongoing and complete indifference: ‘We never speak a word to the servant who waits on us for twenty years; we condescend to employ a tradesman, keeping him at a proper distance, mind’, while ‘of his workmen we know nothing, how piteously they are ground down, how they live and die, here close by us at the backs of our houses; until some poet like Hood wakes and sings that dreadful “Song of the Shirt”; some prophet like Carlyle rises up and denounces woe; some clear-sighted, energetic man like the writer of the Chronicle travels into the poor man’s country for us, and comes back with his tales of terror and wonder’ (Thackeray: 1850, 93).

The ‘writer of the Chronicle’ was, of course, an old friend from Thackeray’s misspent youth in Paris and the early days of Punch, the 37-year-old Henry Mayhew; and this series of articles, beginning in 1849, was the foundation of his epic social study, London Labour and the London Poor.

Nowadays, in the mainstream of popular history and the academy, London Labour and the London Poor is a canonical Victorian text of monolithic proportions. It is the nonfiction counterpart of Dickens’ finest work, an essential primary source for any historian of nineteenth-century England, and a gift that keeps on giving for historical novelists and dramatists. I studied Henry Mayhew for ‘O’ and ‘A’ level history, for example, for all three of my degrees, and I’m still reading him now. It is therefore easy to imagine him as one of Lytton Strachey’s ‘Eminent Victorians’, a great crusading journalist and respected literary celebrity. That was certainly my perception of him as a school kid. The real story, however, is much more interesting that that…

Mayhew, born on November 25, 1812, was the fourth son of the prominent London solicitor and self-made man, Joshua Mayhew, and one of seventeen children. Although quite rich, Joshua was a miser by nature, dictatorial and quick to anger. He wanted all his sons to follow in his footsteps, and apprenticed them to himself, charging the cost against their portions of his estate. Henry, on the other hand, wanted to be a research chemist and attempted to study in his own time after his father dismissed the idea. A bright but feckless scholar, Henry had scandalised the family by dropping out of Westminster School to avoid a flogging. His father sent him to sea, which did not work out either, after which he did his time in the family law firm until a careless clerical error resulted in Joshua narrowly avoiding being in contempt of court. Henry was now absolutely the black sheep of the family, and father and son would not speak for several years.

Henry drifted through his twenties in London, splitting his time between homemade chemical experiments and the bohemian world of comic journalists, dramatists and penny-a-liners, while never seeming to commit to either. ‘Literary or scientific today?’ was a common greeting from his friends. He moved in the same circles as Dickens, Thackeray and Douglas Jerrold, whose daughter Jane he would later marry, and authored a successful farce called The Wandering Minstrel in 1834 that helped keep him afloat. He was party to the establishment of several comic journals, most notably Figaro in London, which he edited from 1835 to 1839, and culminating in the foundation, with Mark Lemon and Stirling Coyne, of Punch in 1841, Mayhew being a joint editor with Lemon. Unseated by new owners the following year, Mayhew hung around at Punch as ‘suggestor in chief’ until 1845, leaving to establish his own daily newspaper, the Iron Times, to capitalise on railway mania. Having missed the boom, the project failed the following year, and, hopelessly over-extended, Mayhew went bankrupt, fracturing his relationship with his father forever. For the sake of his wife and his two children, he was not quite disinherited, but of a £50,000 estate, he was left £1.00 a week on the death of his father in 1858, to be forfeit if he spent it on anything other than basic personal maintenance, with an additional £2.00 going to his wife. Money given for support of the children during this crisis was to be considered a loan repayable at 5 percent interest. In a demining barb in Joshua’s will, he had written ‘To my son Henry I cannot make any personal bequest because he cannot possess any property to his own use’. (Qtd. in Humpherys: 1977, 10). Having been the only son to actually pass the bar, Henry’s brother Alfred was rewarded with the major part of Joshua’s estate.

Less bothered, apparently, by the shame than his father, Mayhew bounced back as a popular novelist, co-authoring with his brother Augustus The Greatest Plague of Life (1847), a satire on middle-class wives and their servants, and Whom to Marry (1848), a novel with some conceptual similarities to Vanity Fair. Both mock the social pretensions of the bourgeoisie, also a favourite subject of Punch, and were illustrated by George Cruikshank. Two further novels followed The Good Genius That Turned Everything into Gold and The Magic of Kindness. Although still essentially light-hearted, these began to explore moral and social themes that would later become prominent in the project for which Mayhew is best known.

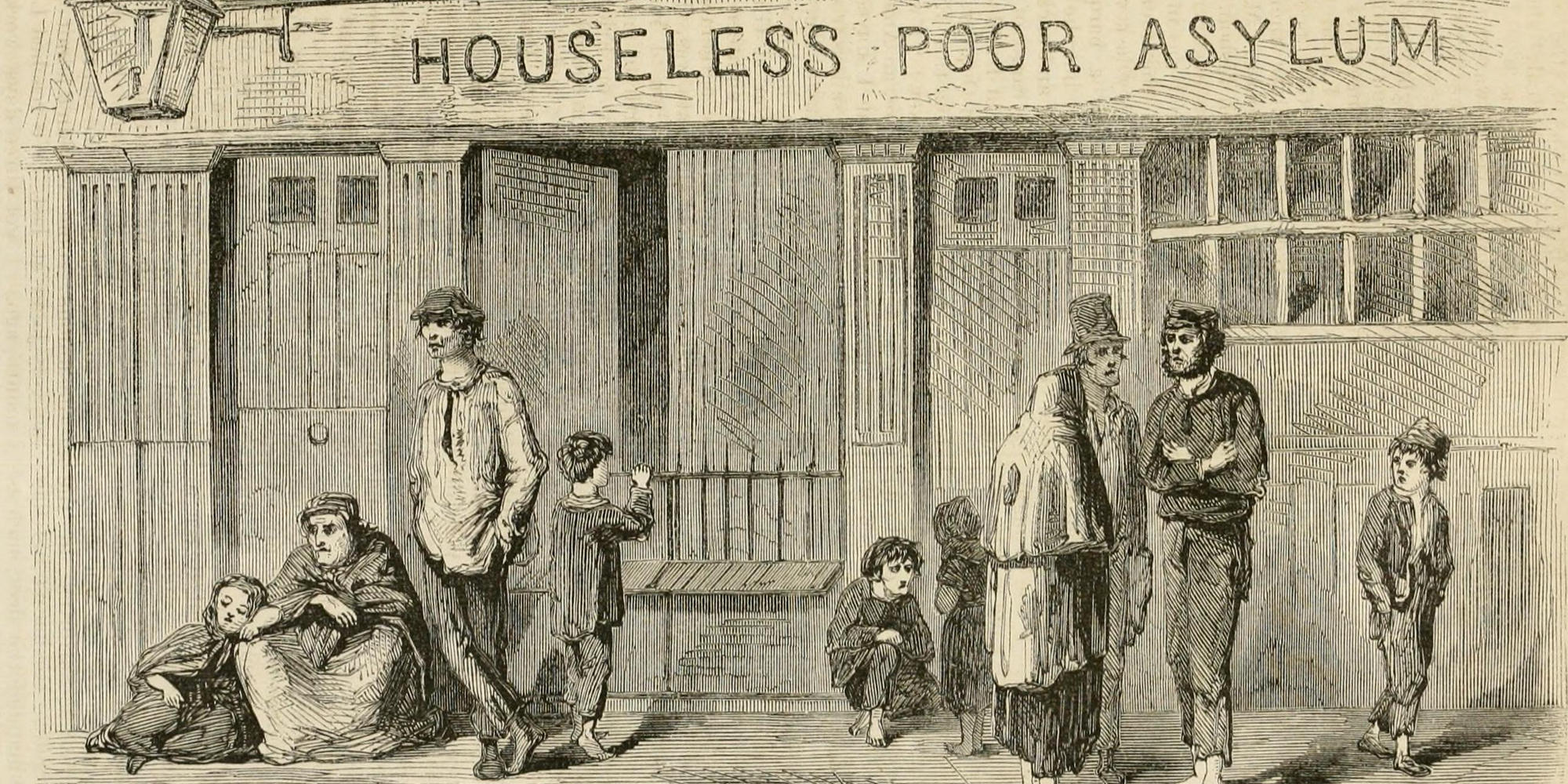

London Labour and the London Poor did not spring fully formed from the mind of Mayhew. Its origins can be seen, however, in a report, he wrote for the Morning Chronicle on Jacob’s Island, a notorious slum in Bermondsey where Dickens had set the climax of Oliver Twist in 1838. As The Times had become more conservative, the rival Chronicle had increasingly adopted a reformist agenda, particularly towards sanitation and health in the growing urban rookeries. Mayhew was originally commissioned in the wake of the cholera epidemic of 1848-1849, in which the worst outbreaks occurred in the worst of the slums; Jacob’s Island being as foul in the summer of 1849 as it had been when Bike Sikes died in the filthy mud of ‘Folly Ditch’.

‘A visit to the cholera districts of Bermondsey’ was a powerful piece of journalism, in which Mayhew combined his interest in chemistry with the devices of a novelist:

On entering the precincts of the pest island, the air has literally the smell of a graveyard, and a feeling of nausea and heaviness comes over anyone unaccustomed to imbibing the musty atmosphere. It is not only the nose, but the stomach, that tells how heavily the air is loaded with sulphuretted hydrogen; and as soon as you cross one of the crazy and rotting bridges over the reeking ditch, you know, as surely as if you had chemically tested it, by the black colour of what was once the white-lead paint upon the door-posts and window-sills, that the air is thickly charged with this deadly gas.

Notably, he also gave various inhabitants a voice, interviewing and then quoting directly:

We crossed the bridge and spoke to one of the inmates. In answer to our questions, she told us she was never well. Indeed, the signs of the deadly influence of the place were painted in the earthy complexion of the poor woman. ‘Neither I nor my children know what health is,’ said she. ‘But what is one to do? We must live where our bread is. I’ve tried to let the house, and put a bill up, but cannot get anyone to take it.’ (Mayhew: 1849, 4).

He goes on to report that locals had no choice but to draw their drinking water from the same ditch into which rotting animal carcasses, industrial waste and, by implication, human excrement were discarded.

This was powerful stuff, a vivid mix of art, science and drama. After years of select committees, royal commissions, questions in the House and earnest essays by doctors, Chronicle readers reacted to Mayhew’s revelations as if they were new, as evidenced by Thackeray’s response. It was a cultural tipping point; the middle classes finally noticed the conditions in which the majority of the urban working classes had to live. Almost immediately after it appeared, the Chronicle announced a huge investigation to be entitled Labour and the Poor, which ‘proposed to give a full and detailed description of the moral, intellectual, material and physical condition of the industrial poor throughout England’ (Qtd. in Humpherys: 1971, xiii). Different writers would report from across the country, while Mayhew would be the ‘metropolitan correspondent’. Mayhew later claimed credit for the idea, although the Chronicle denied this.

Mayhew’s ‘letters’, published three times a week, were a sensation, as he set out to describe the ‘poor of London’ in terms of different classes – ‘as they will work, they can’t work, and they won’t work’ – and the different causes of their poverty. It was an ambitious piece of social investigation, and over the following year, Mayhew was in his professional element, on a good salary, his work supported by a small army of assistant writers, researchers and stenographers and with a cab constantly on call. He interviewed skilled and unskilled labourers and tradesmen, seamstresses, merchant seamen, the inhabitants of low lodging houses and teachers and pupils at ragged schools. Most of his letters followed the same structure, beginning with an overview of the history and nature of his subject, followed by interviews in the first person, often reproducing the idioms and dialect of the speaker, and concluding with Mayhew’s own descriptions, observations and conclusions. His scientific side was always on display, with an urge to quantify, define, analyse and categorize, oddly in balance with his traits as a novelist and dramatist and, increasingly, an activist.

Although Mayhew saw himself as a dispassionate and impartial social investigator, his decision to give the poor a voice was in itself a partisan and radical act. He ultimately broke with the Chronicle at the end of October 1850, in a dispute over the political censorship of his work and the reporting of the adverse effect of free trade on wages in the inequities of piecework and the ‘sweating’ system of labour. This came to a head when he took the side of garment workers over their employer, H.J. and D. Nicholl of Regent Street, one of the Chronicle’s prominent advertising clients.

Despite now being once more freelance, Mayhew continued to publish his ‘letters’ in tuppenny pamphlets, now with a focus on the London ‘Street Folk’ – sellers, traders, street performers, artisans, labourers, and criminals, men, women and children – beginning with a vast exploration of the culture of costermongers, Cockneys hawking all manner of goods out of baskets and barrows from dawn till dusk and the main suppliers of food to the working classes. Initially, this subject was intended to be an introduction to the major work, but Mayhew’s obsession with minute particulars, statistical analysis, endless subclassification and the inability to let a small sample of interviewees represent the whole caused this study to balloon and, though fascinating, completely lose direction. There were meticulous articles on the sale of everything from fried fish and baked potatoes to ‘street literature’ (ballads, Newgate calendars and pornography), the licentiousness of street kids, the disposition of donkeys, penny theatres and the costers’ taste for Shakespeare:

Love and murder suit us best, sir; but within these few years, I think there’s a great deal more liking for deep tragedies among us. They set men thinking, but then we all consider them too long. Of Hamlet we can make neither end nor side; and nine out of ten of us — ay, far more than that — would like it to be confined to the ghost scenes, the funeral, and the killing off at the last. Macbeth would be better liked if it was only the witches and the fighting (Mayhew: 1851, 15).

‘Sermons or tracts’, meanwhile, ‘gives them the ’orrors’.

The series ran until February 1852, after which a dispute with his printer, George Woodfall, over money caused the publication to cease, in midsentence in fact. By this point, the first volume of what was now called London Labour and the London Poor comprising bound unsold parts was in circulation, but the iconic social survey we know today was still several years from publication…

Stephen Carver

WORKS CITED

Humpherys, Anne (ed) (1971). Voices of the Poor. Oxon: Frank Cass & Co.

Humpherys, Anne. (1977). Travels into The Poor Man’s Country. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Mayhew, Henry. (1849). ‘A visit to the cholera districts of Bermondsey’ Morning Chronicle, September 24.

Mayhew, Henry. (1851). London Labour and the London Poor; a cyclopaedia of the condition and earnings of those that will work, those that cannot work, and those that will not work. Vol I. London: G. Woodfall and Son.

Reynolds, G.W.M. (1848). The Mysteries of London. Vol I. London: George Vickers.

Thackeray, W.M. (1850). ‘Waiting at the Station’. Punch, March 9.

Books associated with this article