Lord Byron

2024 marks the 200th anniversary of poet Lord Byron’s death. Sally Minogue looks at his writing and his life, and the age-old question as to whether we can separate the two.

It’s difficult to write about George Gordon, Lord Byron, without referring to the soubriquet ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’, so let’s get that out of the way at the start. His lover Lady Caroline Lamb’s description may have been born out of personal bitterness and distress, but it has clung to Byron like a burr. It is also a phrase of succinct marketing genius. Who would not want to know more about a writer thus described?

Byron’s grotto, Portovenere

As I quickly found with another bad boy, Dylan Thomas, when a poet lives a life that breaks most social norms, it is the life that dominates the writer’s later reputation rather than the nature of the writing itself. Thus it was also with Byron. So can we extricate the writing from the life? This question recurs often when we approach our literary heroes. Byron is an egregious example, since his life was relentlessly dissolute. But it is a question which also occurs with Thomas Hardy, who wrote a heart-breaking series of poems about his wife’s death, after a long coldness towards her for a number of years as they lived in separate parts of the same house. It occurs in a completely different way with Virginia Woolf, who writes with experimental verve and psychological clarity about the existential void that lurks beneath all our lives, while writing letters of breath-taking and pusillanimous snobbery. These two examples bother us because of the perceived mismatch between the work and the life. Can Woolf really have had such insights into a characterizing quality of existence, when she was so dismissive of one section of humanity, or to be absolutely clear, one class? Wasn’t Hardy’s sudden grief rather convenient for a poet?

Dylan Thomas’s is a different case, and more closely akin to Byron’s. Here the lives are self-destructively decadent, appetite-driven, characterized by appalling treatment of those most close to them, without apparent concern for anyone other than themselves. The question here is, should we consider the poetry at all when the life lived is so destructive, of the self but, more notably, of others? As the ‘mad, bad, etc’ description of Byron, and its lure over two centuries, suggest, in fact the problematic personal reputation only piques our interest. But then that reductive description attaches itself also to the work, as it did, damagingly, with Dylan Thomas. Our task then as readers is to try to look at the work afresh and see what contribution it makes, separately from what we know of the life. Once that is done, we can address the more complex question of how our critical and human responses to the work can be, or should be, influenced by what we know of the life.

Lord Byron in Albanian dress

Byron’s writing, rather like Thomas’s, began when he was young. His first collection, Fugitive Pieces, was published in 1806 when he was only 18, followed by Hours of Idleness when he was 19 (and as he pointed out in his Preface, several poems there had been written two or three years earlier – again much like Thomas). These were in the culture of the time tantamount to self-published works, but nonetheless Hours of Idleness attracted notice from the influential Edinburgh Review. It was hostile, but it was a review. Byron was still at Cambridge. He then embarked on his first ‘serious’ work, English Bards and Scottish Reviewers, a hot response to the Edinburgh Review. Here he revealed his talent for comic satire and his abiding interest in complicated verse forms. English Bards and Scottish Reviewers, while very local to its time and culture, is an astonishingly accomplished piece of work and still ranks as one of Byron’s significant poems, at least insofar as it intimates the poetic skills and qualities to come. It shows his fine disregard for offending the poetic establishment, containing clever pen portraits of the important poets of the time. It has William Wordsworth spot on, suggesting that his poem ‘The Idiot Boy’ makes ‘the Bard the hero of the story’, as indeed he is in so many of those encounters with the ‘ordinary’. He further suggests that Wordsworth Lord Byron

both by precept and example, shows

That prose is verse, and verse is merely prose

The fourth edition of the seminal Lyrical Ballads (Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge) had been published only four years previously, and here was the upstart, albeit Lord, Byron cocking a snook at its revolutionary attempt to use a plainer language. His preface to the second edition of English Bards, 1809, announced: ‘My object is not to prove that I can write well, but, if possible, to make others write better’. Byron is at this point a mere 21, with little poetic output behind him. Yet he is also showing a true satirical ability, and a clever pen, though perhaps one that owes more to Pope in the century behind him than to the current poetic style. Upon which he ups sticks to take the grand tour.

The grand tour was no ordinary venture at this point, 1809, right in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars. Byron’s crossing of Europe towards his intended destination, ‘the East’, was often arduous, sometimes risky as he skirted areas of conflict, the highlight being his venturing into Albania to be entertained by the warlord Ali Pasha, who may have overestimated Byron’s political influence at home by virtue of his title. This and other encounters are featured in Byron’s major work, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, a semi-autobiographical poem which he began during the journey, cross-country and by sea, back to Missolonghi and eventually Athens and thence Constantinople. Thus started Byron’s love affair with Greece. A major element in this passionate feeling was his classical education. The power of the past was immediate to him here. Places and events he had read about in classical epic were actual: Delphi, Parnassus, the Hellespont (which he delighted in swimming across in imitation of the myth of Leander), the site of the city of Troy. His remarks on his sense of the history of place, informed by his reading of classical literature, are echoed by Rupert Brooke when he knows he is being sent to the Dardanelles (what was the Hellespont) in the First World War. Writing to Violet Asquith in 1915, he says: ‘ Oh Violet it’s too wonderful for belief … I’m filled with confident and glorious hopes … Will Hero’s tower crumble under the 15 in. guns? … Will the sea be wine-dark and unvintageable?’ (He is referring to the same myth, Hero being the one that Leander was swimming the Hellespont to reach.) For Byron, this was the time of the stripping of large parts of the sculptures of the Acropolis by Lord Elgin (which took place between 1801 and 1812), the much-disputed ‘Elgin marbles’. Perhaps in thinking about what should happen to these today, we should take our lead from Byron, who was in no doubt that Elgin’s activities were a form of looting. Again, this features in Childe Harold.

J.M.W. Turner: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage

It’s worth reminding ourselves that Byron is still only 22 at this point (1810). Whatever the trail of destruction he left during this period in personal and moral terms, there is a serious engagement with literature, with the revolutionary politics of the time, with a sense of the past as it informs the present, and these come to fruition in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Lord Byron

When Byron returned to England in 1811, it was to narrowly miss seeing his mother before she died. In 1812 he gave a significant maiden speech in the House of Lords, and shortly afterwards the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage were published. In Byron’s words, ‘I awoke one morning and found myself famous’. Childe Harold, written in the intricate rhyme scheme of the Spenserian stanza, ironises the mediaeval quest of the would-be knight, here displaced on to the contemporary landscape of Byron’s world. The notion of the Byronic hero – loosely based on Byron himself – is given full expression here, and was to become a characterising dimension of Romanticism. Thus though it is a poem that speaks to and of its time, it can still appeal to the current reader since it expresses the world-weary search for inspiration and purpose. It is also an interesting travelogue for today’s reader, taking us through Spain, Portugal, Albania, Greece, and reflecting as I have said before the underpinning of these places by classical mythology which is brought to life in the poem. There is also a powerful, clever description of a bullfight, with a brilliant evocation of the matador. Byron in this poem is writing as no-one else was at this time. It couldn’t be more different from the worthy Wordsworth Byron had previously skewered (though he came through Shelley’s tutelage to respect Wordsworth’s poetry). Its clever verse form carries the reader along and allows for each stanza to create its own word picture while contributing to the larger narrative. It has emotional depth in terms of its exploration of the inner workings of the ‘hero’ but there is also plenty going on, action, travel, incident.

For all Byron’s exploits, at the heart of his poetry is a sorrowful self:

‘Tis night, when Meditation bids us feel

We once have loved, though love is at an end;

The heart, lone mourner of its baffled zeal,

Though friendless now, will dream it had a friend …

Alas! When mingling souls forget to blend,

Death hath but little left him to destroy!

Ah! Happy years! Once more who would not be a boy?

(Canto II, stanza 23) Lord Byron

Lord Byron on His Deathbed

If there weren’t such moments in his poetry, there would be less impetus to read him. But what makes him ‘Byronic’ is also that which has energy, wit, cruelty even, and above all the ability to laugh at himself and at life. These qualities are most to the fore in his epic Don Juan, written between 1818 and 1823. Following the well-known story of the grand philanderer Don Juan, an obvious alter ego for Byron himself, Byron gives himself free rein in content and approach whilst keeping to another strict verse form, ottava rima. Byron himself made light of the poem, writing to his publisher John Muuray in 1819, ‘You ask me for the plan of Donny Jonny; I have no plan – I had no plan … Do you suppose that I could have any intention but to giggle and make giggle?’ This approach is highlighted in the verse which Byron scribbled on the back of the manuscript of Canto 1:

I would to heaven that I were so much clay,

As I am blood, bone, marrow, passion, feeling –

Because at least the past were pass’d away –

And for the future (but I write this reeling,

Having got drunk exceedingly today,

So that I seem to stand upon the ceiling)

I say – the future is a serious matter –

And so – for God’s sake – hock and soda water!

While this might seem light and shallow, it surely contains something dark and deep. This is, I think, what keeps us reading Byron, the contradiction at the heart of his writing.

Certainly, his end was serious, in that he committed himself to the cause of Greek independence, raising a sort of private army, though he was disillusioned by the infighting amongst the Greeks themselves. Before he could launch a planned attack on the Turkish-held fort at Lepanto, Byron contracted a fever, possibly malaria, and died. His death mirrors that of Brooke’s less than a century later in Skyros, also from a fever (initiated by an insect bite). Neither of them had the heroic deaths in combat they might have wished.

Byron’s personal life is a catalogue of violent sexual and emotional passions, for both men and women, some of whom would have today counted as minors, one of whom was his half-sister Augusta; these were often followed almost immediately by equally violent disconnections, betrayals and hostile rejections of those he had once appeared to love. No wonder he found sympathy for Don Juan. Although his love for Augusta and hers for his seems to have been deep, lasting and true, he wrought havoc for many with whom he was connected. Do we weigh all this against the poetry? Do we accept that the poetry is in part informed by and fired by it? Or do we try to look at Byron’s work dispassionately? That latter adverb is not one that he would have liked.

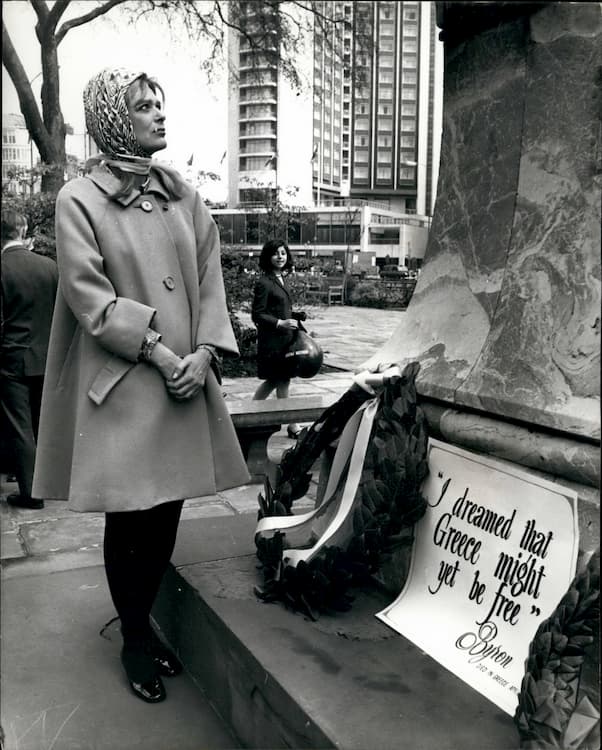

Melina Mercouri lays a wreath on Byron’s statue 1964

Life is a messy business, and Byron’s was messier than most. His poetry gives us an original voice, a satirical, witty and exuberant one, and his mastery of the complicated verse forms and rhyme schemes which seemed to give him such pleasure was perhaps the one area in which he exerted full control. At times he can shock us not with his lack of concern for conventional mores, but with a deep and tender emotion, as in the Hebrew Melodies, which include ‘She Walks in Beauty Like the Night’, or in the ballad-like ‘So, We’ll Go No More A Roving’, a touching farewell to the pleasures of youth.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

That could stand as his own epitaph, dead at 36, while engaged in a revolutionary struggle in which he had a deep belief. His own last journal entry was written on January 22nd 1824 in Missolonghi, reflecting on his 36th birthday, which would, unknown to him, be his last. (The well-read and classically steeped Rupert Brooke must surely have had these somewhere in mind when he wrote ‘The Soldier’/ ‘If I should die…’). These are Byron’s last stanzas:

If thou regret’st thy Youth, why live?

The land of honourable Death

Is here: – up to the Field, and give

Away thy Breath.

Seek out – less often sought than found –

A Soldier’s Grave, for thee the best;

Then look around, and choose thy Ground,

And take thy Rest!

I am indebted to David Ellis, Critical Lives: Byron, Reaktion Books Ltd, 2023

Wordsworth publish the novels of Thomas Hardy and Virginia Woolf, and the works of Dylan Thomas.

For more information on Byron’s Life and Works, visit: The Byron Society

Our edition is here: Selected Poems of Lord Byron

Main image: Memories of Lord Byron on Island of Kefalonia, Greece Credit: Mike P Shepherd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Byron’s Grott, Portovenere Credit: Chris Pancewicz / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Byron in Albanian national dress. Credit: Classic Image / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: J.M.W. Turner: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Credit: The Print Collector / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Lord Byron on His Deathbed. Credit: GL Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: Melina Mercouri lays a wreath Byron’s statue, 1964. Credit: Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article