Nesbit & Hubert Bland: The Truth Behind ‘Woman of Stone’

You might recall that just before Christmas last year I wrote a post about the BBC’s ‘Ghost Story for Christmas’ in anticipation of Woman of Stone. This was an adaptation of E. Nesbit’s 1887 story ‘Man-size in Marble’ by Mark Gatiss, who has breathed new life into the long-running series. Since then, I have had the pleasure of revisiting Nesbit’s supernatural and horror fiction for Wordsworth Editions, selecting and editing a new edition of what she called her ‘Grim Tales’ which has just been published.

It must have come as quite a surprise to many BBC viewers that Woman of Stone was based on a tale by E. Nesbit, renowned Victorian and Edwardian children’s writer and author of The Railway Children. Nesbit in fact wrote horror fiction throughout her career, continuing after her breakthrough as a bestselling children’s author with The Story of the Treasure Seekers in 1899, the novel that introduced the ‘Bastable’ family to equally enchanted young and adult readers, and which had the same kind of cultural impact that the ‘Harry Potter’ books would almost a century later. But then, there’s probably a lot most casual readers don’t know about Edith Nesbit. Gatiss’ drama was therefore doubly innovative in introducing a new generation to Nesbit’s horror writing, while at the same time using a framing narrative to tell some of the darker secrets of her private life.

It must have come as quite a surprise to many BBC viewers that Woman of Stone was based on a tale by E. Nesbit, renowned Victorian and Edwardian children’s writer and author of The Railway Children. Nesbit in fact wrote horror fiction throughout her career, continuing after her breakthrough as a bestselling children’s author with The Story of the Treasure Seekers in 1899, the novel that introduced the ‘Bastable’ family to equally enchanted young and adult readers, and which had the same kind of cultural impact that the ‘Harry Potter’ books would almost a century later. But then, there’s probably a lot most casual readers don’t know about Edith Nesbit. Gatiss’ drama was therefore doubly innovative in introducing a new generation to Nesbit’s horror writing, while at the same time using a framing narrative to tell some of the darker secrets of her private life.

It’s been a few months since Woman of Stone was broadcast on Christmas Eve now, so hopefully spoilers won’t be a problem. Of Nesbit’s forays into horror and the supernatural, this story of the statues of wicked medieval knights returning to a ghastly parody of life on Halloween is by far the best known, being a favourite in anthologies of Victorian ghost stories. (Mark Gatiss has said that this was ‘the very first ghost story I ever read’ and I think it might’ve been one of mine too.) It plays on a very ancient human fear of the inanimate coming to life, a fear that had haunted Edith since childhood, when she had been traumatised by a visit with her older sisters to see the naturally mummified corpses beneath the church of St. Michel in Bordeaux when she was about ten. This was an experience about which she wrote with chilling candour in My School Days, a memoir serialised in The Girl’s Own Paper between 1896 and 1897:

Round three sides of the room ran a railing, and behind it—— standing against the wall, with a ghastly look of life in death—were about two hundred skeletons. Not white clean skeletons, hung on wires, like the one you see at the doctor’s, but skeletons with the flesh hardened on their bones, with their long dry hair hanging on each side of their brown faces, where the skin in drying had drawn itself back from their gleaming teeth and empty eye sockets. Skeletons draped in mouldering shreds of shrouds and grave clothes, their lean fingers still clothed with dry skin, seemed to reach out towards me. There they stood, men, women, and children, knee-deep in loose bones collected from the other vaults of the church, and heaped round them. On the wall near the door I saw the dried body of a little child hung up by its hair.

In the evening, Edith was left alone in a hotel room while her mother and sisters went to dinner downstairs, where she became convinced that a curtained alcove concealed not beds but more mummies. When a young waiter arrived with her dinner, she clung to him in abject terror and the kindly young man, though he spoke no English and she no French, sat with her until her mother returned. Nesbit described the experience as ‘the crowning horror of my childish life,’ and she never got over it, having thereafter – like many of the protagonists in her horror stories – a ‘mortal terror of darkness.’ This she tried to banish by ‘making mummies,’ handcrafted effigies built out of coat hangers, broken umbrellas, old clothes… whatever she could scavenge around the house, with painted paper masks for faces like the disturbing ‘Ugly-Wuglies’ in her children’s book The Enchanted Castle (1907), Guy-like dummies bought to life by a magic ring. The idea was to remove the memory’s morbid power through familiarity, and she tried this, too, with her own children, by keeping skulls and bones about the family home to make the concept of death less frightening. But like the ‘Ugly-Wuglies’, Edith never really shed the fear that dead things and creepy representations might just come back to life:

The draped effigy just behind him worried him again. He had been trying, at the back of his mind, behind the other thoughts, to strangle the thought of it. But it was there—very close to him. Suppose it put out its hand, its wax hand, and touched him. But it was of wax: it could not move. No, of course not. But suppose it did?

This was a recurring theme throughout her horror fiction, these ‘things that walk’ having an innate hatred of the living like the evil statues in ‘Man-size in Marble’ and the waxworks of the Musée Grévin (‘as near life as death is’) – another gothic French attraction that kept her awake at night and inspired her 1905 story ‘The Power of Darkness’, quoted above.

Nesbit’s original ‘Man-size in Marble’ is a relatively straightforward and effective ghost story. Bohemian newlyweds Laura and her unnamed husband (the narrator of the tale), rent a country cottage because they can’t afford to live in London. He paints and she writes. Money is tight but they are happy and very much in love. Their housekeeper, Mrs. Dorman, is a mine of local folklore, and in requesting the night off on Halloween, she tells the husband the story of the marble statues of two medieval knights in the local church coming to life on this night and returning to the site of their old home, where the cottage now stands. The man knows his wife is quite nervous, and decides to keep the story to himself. You can guess what happens on Halloween…

Gatiss keeps to the basic premise in Woman of Stone as far as the statues are concerned but rewrites Laura (played by Phoebe Horn) and ‘Jack’ (Éanna Hardwicke). Whereas Nesbit’s couple are idealised and blissfully happy, Gatiss’ version has already fallen into domestic abuse. Jack is a failed artist who belittles everything Laura does creatively, although her ‘odd silly little story for the periodicals,’ as he puts it, supports them both; he views her as nothing but his property and breeding stock, talking endlessly of children. A symbol of corrupt and hypocritical Victorian patriarchy, his jealousy has driven them out of London in search of what he calls a ‘fresh start’, and she still bears the bruises. Mrs. Dorman (Monica Dolan) notices this, and in a moment of feminine solidarity she laments the fact that the world belongs to men, and that ‘They’re all as one,’ conflating her (presumably also violent) husband with Jack. The way Laura reacts with obvious fear to Jack’s fake bonhomie is particularly disturbing, as are the pet names he uses for her. In the original story these are sweet and endearing, but here they become patronising and controlling. Laura has nightmares about the knights murdering their wives (the new backstory), only it’s her and Jack.

In a strange little intertextual nod to British character actor Lionel Jeffries, Gatiss has Jack use ‘Capital!’ and ‘Imperial!’ as expressions of enthusiasm and delight. These were also terms used by Jeffries when he portrayed Professor Cavor in the 1964 film version of H.G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon. (Gatiss had also played this character in his own adaptation of the story for BBC Four in 2010.) Lionel Jeffries was, of course, the director of the much-loved 1970 film version of The Railway Children starring Jenny Agutter and Bernard Cribbins. So despite having Edith lament, ‘They always want to hear The Railway Children…’ (as opposed to her genre fiction for adults), Gatiss can’t resist sneaking in a reference himself, even though the point of the drama is to show that E. Nesbit was much more than just a children’s author.

Anyway, into this mix comes the Indian GP ‘Zubin’ (Mawaan Rizwan), replacing the original Irish doctor of the story, an intellectual who immediately connects with Laura. Jack becomes obsessively jealous, and privately invites Zubin to meet him at the church to have it out the night the statues are supposed to walk (now shifted to Christmas Eve for the sake of the seasonal ghost story). Jack sees the empty crypt where the statues usually lay, but Zubin doesn’t believe him. When they return to the cottage, coincidently at the same time as Mrs. Dorman, Laura has been strangled. The story concludes with Jack being hanged for murder, and Mrs. Dorman’s memory of finding a broken marble finger in Laura’s hand – the denouement of the original story – which she conceals, thereby removing the only evidence that might corroborate Jack’s story of the walking statues and save him from the gallows.

This narrative is, in turn, framed by an aging and terminally ill Nesbit (the perfectly cast Celia Imrie) telling her doctor (also played by Rizwan) the story. This is where it gets really interesting. As Nesbit flirts cheekily with the younger man, puffing away on a cigarette in a long holder (a trademark of the original Edith), she also reveals details of her own marriage, explaining, ‘I took in a friend despoiled by a married man … We raised the child as our own.’ She concludes that she later discovered the ‘despoiler’ had been her own husband, Hubert, adding that, ‘I forgave – probably unwisely.’ Gatiss’ clear implication is that Edith’s horror stories allowed her to act out revenge scenarios against Hubert, having Nesbit describe his version of ‘Man-size in Marble’ as ‘A dying woman’s little fantasy.’ He also connects Nesbit to Laura by giving them the same nightmare, Edith’s prefacing the drama. She wakes from it as her doctor calls, then she tells him the story. The real story, however, is much more complicated, and much worse.

This narrative is, in turn, framed by an aging and terminally ill Nesbit (the perfectly cast Celia Imrie) telling her doctor (also played by Rizwan) the story. This is where it gets really interesting. As Nesbit flirts cheekily with the younger man, puffing away on a cigarette in a long holder (a trademark of the original Edith), she also reveals details of her own marriage, explaining, ‘I took in a friend despoiled by a married man … We raised the child as our own.’ She concludes that she later discovered the ‘despoiler’ had been her own husband, Hubert, adding that, ‘I forgave – probably unwisely.’ Gatiss’ clear implication is that Edith’s horror stories allowed her to act out revenge scenarios against Hubert, having Nesbit describe his version of ‘Man-size in Marble’ as ‘A dying woman’s little fantasy.’ He also connects Nesbit to Laura by giving them the same nightmare, Edith’s prefacing the drama. She wakes from it as her doctor calls, then she tells him the story. The real story, however, is much more complicated, and much worse.

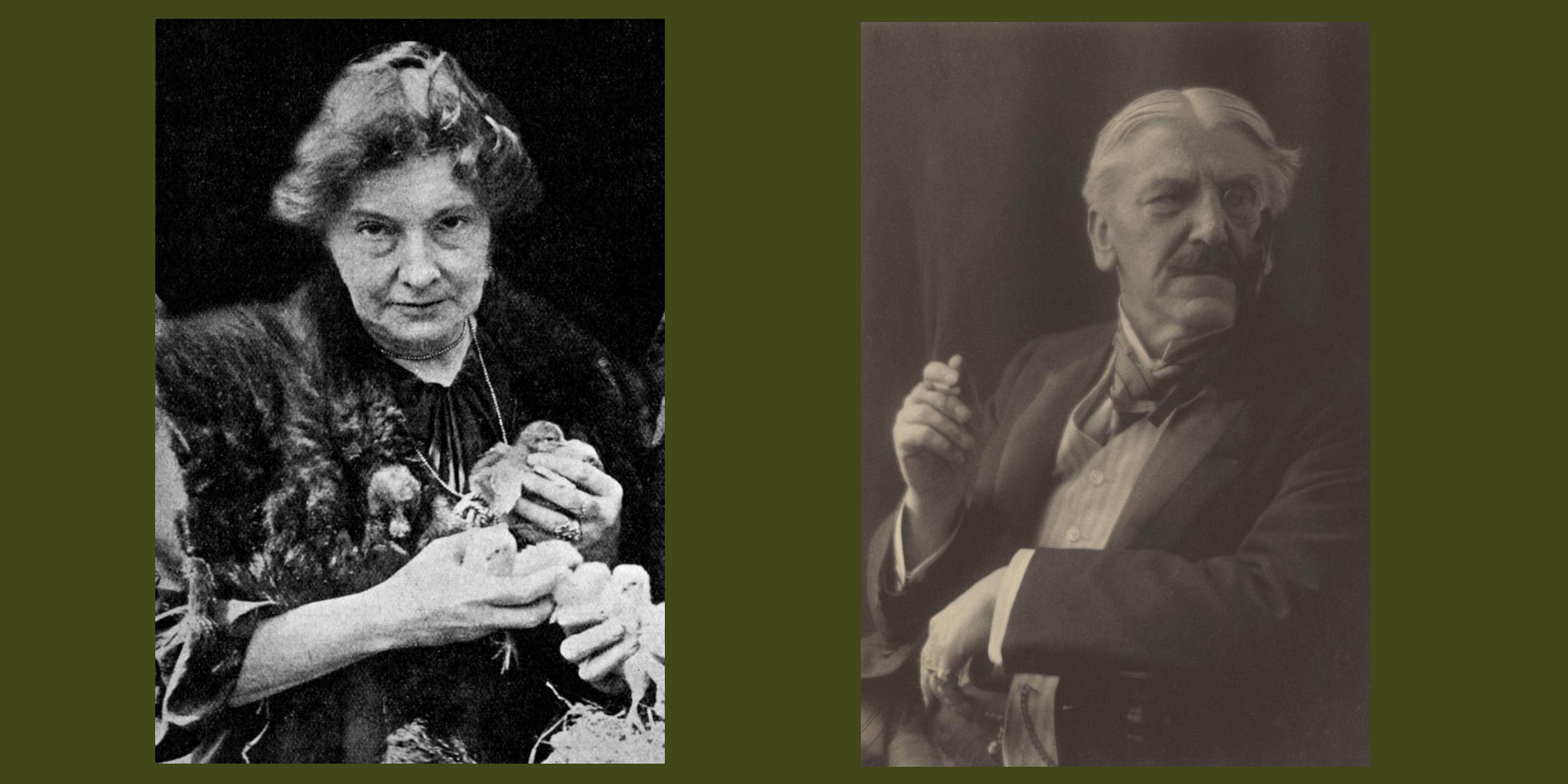

Always a free spirit, Nesbit had married young and hastily. She had met the bank clerk Hubert Bland when she was eighteen and he was twenty-one. Aside from a notoriously high-pitched voice (H.G. Wells described it as ‘fluting’), Hubert was well-read, highly intelligent, and by all accounts sexually magnetic, affecting a dashing ‘man-of-the-world’ persona with hints of a military bearing. (In reality, his parents had not had the money to buy him a commission.) He swept Edith off her feet despite having a fiancée, his mother’s paid companion, Maggie Doran, with whom he already had a son. Edith knew nothing about Maggie when she married Hubert in 1880, seven months pregnant by him herself.

Not long after the birth of their son Paul (to whom The Railway Children is dedicated), Hubert contracted smallpox. When he recovered, he discovered his business partner in a small brush factory had absconded with whatever money they had. Hubert then relapsed, leaving his young wife with no family income whatsoever. Like one of her own resourceful heroines, Edith assessed her saleable skills: she could paint, she had a gift for public recitation, and she could write. And by these trades, she supported the family, making hand-painted greeting cards (to which she also added sentimental verses), speaking at private functions, and hawking stories and poems around Fleet Street, working contacts she’d already made as an early career writer, placing material in journals like Longman’s Magazine, The Argosy, Belgravia, The Weekly Dispatch, and Sylvia’s Home Journal. (She would not receive regular and lucrative commissions from The Strand Magazine until 1899.) She would later dramatise the miserable process of trying to sell your own writing in her 1909 novel Daphne in Fitzroy Street.

It was at the offices of Sylvia’s Home Journal that Nesbit met and befriended the professional reader Alice Hoatson in 1882, introducing her to Hubert. The Blands had by then had a second child, Iris, and Alice soon started helping Edith out around the house. Alice finally moved in permanently as a childminder in 1886, about a year after the birth of the Bland’s second son, Fabian – destined to die tragically young after a botched operation – and after Edith had just suffered a stillbirth. The unmarried Alice was pregnant at the time. It’s not clear exactly when Alice had become Hubert’s mistress, or when Edith realised, but she had two children by him – Rosamund and John – who Edith raised as her own. Alice lived with the Blands until Hubert’s death in 1914, and with Edith for another three years after that. She continued the pretence that Rosamund and John were her ‘niece and nephew’ until she died in 1944. Hubert’s first victim, Maggie Doran, also remained a friend of the family, Edith taking her in when she became terminally ill in 1903.

George Bernard Shaw – a close friend of Hubert who helped him become established as a journalist – described him as:

A Tory Democrat from Blackheath, who sported fashionable clothes, wore a monocle, and maintained simultaneously three wives, all of whom bore him children. Two of the wives lived in the same house. The legitimate one was E. Nesbit…

H.G. Wells, a former friend, was even less forgiving in his Experiment in Autobiography:

The incongruity of Bland’s costume with his Bohemian setting, the costume of a city swell, top-hat, tail-coat, greys and blacks, white slips, spatterdashes and that black-ribboned monocle, might have told me, had I had the ability then to read such signs, of the general imagination at work in his persona, the myth of a great Man of the World, a Business Man (he had no gleam of business ability) invading for his own sage strong purposes this assembly of long-haired intellectuals. This myth had, I think, been developed and sustained in him, by the struggle of his egoism against the manifest fact that his wife had a brighter and fresher mind than himself, and had subtler and livelier friends.

Wells and the Blands had been close but had fallen out when he was caught trying to run away with Rosamund (he was married to his second wife at the time), claiming that he was trying to save her from her father’s ‘illicit advances’. To Wells, Hubert was the epitome of male privilege and sexual hypocrisy, although Wells, too, was guilty of having multiple affairs, and had left his first wife, Isabel, for one of his students, Amy Catherine ‘Jane’ Robbins, and then fathered a child with the writer Amber Reeves.

But despite what her first biographer, Doris Langley Moore, euphemistically called Hubert’s ‘one deplorable bad habit’ (he even tried to seduce his daughter’s schoolfriends), Edith seemed to have loved him. This was also true of many other men and women in the socialist and literary intellectual set in which the Blands were prime movers as founder members of the Fabian Society – one of the founding organisations of the British Labour Party – such as proto-feminists like Annie Besant and Eleanor Marx, Russian dissidents Sergius Stepniak and Peter Kropotkin, and cultural influencers like Frank Podmore, William Morris, and Shaw. She acquired her political beliefs and affiliations from Hubert, and the couple collaborated closely at the outset of her literary career, writing stories together under the penname ‘Fabian Bland’. In the household, Hubert was also the only family member who could calm Edith’s volatile mood swings, although it seems likely he was the cause of most of them. And while resisting the ‘free love’ espoused by some of the more radical Fabians, the Bland’s marriage was certainly ‘open’, Edith having a string of affairs with younger literary men like Richard le Gallienne, Richard Reynolds, Oswald Barron (to whom The Treasure Seekers is dedicated), Bower Marsh, and Noel Griffith. Research for The Story of the Amulet at the British Museum also led to a fling with Egyptologist Dr. Wallis Budge. Edith seems to have favoured younger men, who were probably easier to manage, after her intense but disastrous pursuit of her intellectual equal George Bernard Shaw. The problem was that younger men eventually always married girls their own age.

To the modern reader, Hubert was undoubtedly a sexual predator, but Edith seemed unable to function without him. It was his threat to leave if his wife did not accept Alice’s baby that apparently caused her to acquiesce, and when he died in 1914 she was devastated, writing to her friend Mavis Carter: ‘Now that my husband is gone, the close and constant companion and friend of thirty-seven years, my life seems broken off short’ and to her brother, Henry, ‘I do not find I can take much interest in life. Without Hubert everything is so unmeaning.’ She even refused to accept the reality of his death and attempted to revive the body by warming it with hot water bottles and covering it with heavy quilts. After his death, she threw herself into editing a collected volume of his journalism. But were they really soulmates or was this co-dependency? Alice’s daughter Rosamund gave Doris Moore a more realistic account:

I don’t feel that phrase ‘though, or because, she still loved her husband’ is at all adequate to express the tremendous hold he certainly had on her from the moment he met her until he died. It wasn’t simply that she came nobly up to scratch over a big crisis. She could not have borne losing him and there was a danger of that. He didn’t want to lose either of them and I’ve no doubt he used every art of which he was capable to keep them both. And through a lifetime of riots and jealousies he succeeded. After his death they parted, though I feel sure he believed they never would.

And Alice was just as devoted, becoming Hubert’s eyes when he went blind towards the end of his life, reading him books and transcribing his articles. Alice was not given her marching orders until Edith re-married in 1917.

Whatever the complex dynamics of the relationship between Edith, Hubert, and Alice (to whom Edith dedicated the short story collection These Little Ones), the Bland household was not an unhappy one. Instead, it would seem to have been quite the opposite, with numerous enthusiastic accounts left behind in the autobiographies of members of their huge social, political, and professional circle, Wells’ being the only notable exception. Wherever they lived, the Blands kept an open house, with friends encouraged to turn up whenever they liked. Edith loved to throw lavish dinner parties, always with games afterwards, and friends and literary acolytes were drawn along in her wake on impromptu holidays while her children ran wild and barefoot.

Whatever the complex dynamics of the relationship between Edith, Hubert, and Alice (to whom Edith dedicated the short story collection These Little Ones), the Bland household was not an unhappy one. Instead, it would seem to have been quite the opposite, with numerous enthusiastic accounts left behind in the autobiographies of members of their huge social, political, and professional circle, Wells’ being the only notable exception. Wherever they lived, the Blands kept an open house, with friends encouraged to turn up whenever they liked. Edith loved to throw lavish dinner parties, always with games afterwards, and friends and literary acolytes were drawn along in her wake on impromptu holidays while her children ran wild and barefoot.

Edith herself was larger than life in every respect: tall, with her hair cut short in defiance of convention, uncorseted in flowing robes, dripping with bracelets and bangles, a box of hand rolling tobacco and preposterously long cigarette holders forever at her side. Ada Chesterton – journalist and sister-in-law of G.K. Chesterton – left a particularly vivid account:

Mrs Bland was always surrounded by adoring young men, dazzled by her vitality, amazing talent and the sheer magnificence of her appearance. She was a very tall woman, built on the grand scale, and on festive occasions wore a trailing gown of peacock blue satin with strings of beads and Indian bangles from wrist to elbow. Madame, as she was always called, smoked incessantly, and her long cigarette holder became an indissoluble part of the picture she suggested – a raffish Rosetti, with a long full throat, and dark luxuriant hair, smoothly parted. She was a wonderful woman, large hearted, amazingly unconventional, but with sudden strange reversions to ultra-respectable standards. [She did not, for example, support female suffrage.] Her children’s stories had an immense vogue, and she could write unconcernedly in the midst of a crowd, smoking like a chimney all the while.

One of these ‘adoring young men’ was Richard le Gallienne, who later wrote to Doris Moore describing meeting Edith for the first time:

I can still see her, as though it was yesterday, as I first saw her at Hampstead, seated in an armchair with two little children at her side. It was a romantic moment for me, as she was the first poet I had ever seen, and, a youth first come up to London from the provinces, I looked on her with wonder, captivated by her beauty and the charm of her immediately sympathetic response. I fell head over heels in love with her in fact. She was quite unlike any woman I had ever seen, with her tall, lithe, boyish-girl figure, admirably set off by her plain ‘socialist’ gown, her short hair, and her large, vivid eyes, curiously bird-like, and so full of intelligence and a certain half-mocking, yet friendly humour. She had too, a comradely frankness of manner, which made me at once feel that I had known her all my life; like a tom-boyish sister slightly older than myself. She suggested adventure, playing truant, robbing orchards, even running away to sea. I was hers from that moment, and have been ever since.

They would go on to have an affair when he was 23 and she 31, le Gallienne writing an angry poem about Edith and Hubert entitled ‘Why Did She Marry Him?’ which remains a very good question.

In Woman of Stone, Mark Gatiss has done an elegant job of turning ‘Man-size in Marble’ into an allegory of Victorian domestic violence, in fact, of all domestic violence and toxic masculinity, as well as a symbol of Nesbit’s own less-than-perfect marriage. And perhaps this has always been hidden in the original story, written not long after Alice came to stay. Nesbit’s biographer, Julia Briggs, for example, goes as far as to argue that Nesbit is suggesting rape by the statues. It is also notable how many of Nesbit’s horror stories involve either romantic rivalries and love triangles, the seduction of innocent women, or the destruction of happy marriages. One might argue that there is some sort of symbolic punishment being enacted in these. She even drops an entire building on a seducer in ‘The New Samson’, while another is stabbed to death by his victim’s vengeful father as her ghost and ghostly baby look on in ‘Barring the Way’. In ‘Man-size in Marble’, it is difficult not to read Laura and her husband as versions of the newly married Edith and Hubert. They are both bohemian, in love and broke, and the husband even uses the same pet names as Hubert, ‘Wifie’ and ‘Pussy’. The threat is ancient, implacable, and external, and might be read as Hubert’s unbridled sex addiction, or perhaps even manifestations of Maggie and Alice threatening Edith. The couple are warned, as Edith must have been warned about Hubert – her mother certainly didn’t approve – but like the Trojans they pay not heed, leading to a very dark epiphany indeed. The gothic, of course, has also traditionally been a form of coded narrative through which women writers have explored anxieties over motherhood, domestic entrapment, and female sexuality.

Gatiss is certainly reading the story that way, and for the sake of dramatic brevity – Woman of Stone is only thirty minutes long – he’s reduced Hubert’s small army of illegitimate children to one, while transmuting emotional abuse to physical. Again, I would think this is to serve the needs of the drama. The meaning is diluted if the explanation becomes too detailed, and monster though Hubert undoubtedly was, there’s no evidence he was violent. Similarly, how Edith felt about him was also more tragically complicated than Woman of Stone allows. Whatever Hubert’s hold over her was, she was seemingly lost without him. For a more detailed insight into this complex, co-dependant dynamic I would recommend the Nesbit biographies by Moore and Briggs. Writing in 1933, when much had to remain unsaid, Doris Moore later passed her unpublished research onto Julia Briggs, who produced a much more candid book in 1987. Read together, they are a fascinating window into the weird world of the Blands.

Only towards the end of her life was Edith truly free, when she married her friend Thomas Terry Tucker in 1917. ‘The Skipper’ was the captain of the Woolwich Ferry. He was a fellow socialist, and a kind, uncomplicated man of a lower social rank than his new wife. They would have five good years together, living modestly in an eccentric double-bungalow on the Romney Marshes, until Edith’s health began to fail in 1922. A chain-smoker, she died of what was almost certainly lung cancer in the late spring of 1924.

But finally, there had been no more need to share. Soon after their wedding, Edith had written to her brother, ‘for the first time in my life, I know what it is to possess a man’s whole heart.’ Aside from one last supernatural story – ‘The Detective’ (1920) – it is notable that Nesbit wrote no more horror after Hubert’s death.

Main image: E. Nesbit Credit: Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy Stock Photo. Hubert Bland Credit: Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Our edition of Man-size in Marble and Other Grim Tales is available for £4.99 and can be found here.

Image 2 above: The tomb chest of John Fagge and his son in the Lady Chapel of St Eanswith Church, Brenzett, Romney Marsh. This may be the inspiration for Man-size in Marble

Image 3: Nesbit’s grave, St Mary the Virgin, St Mary in the Marsh, New Romney, Kent. Credit: Brian Hartshorn / Alamy Stock Photo

Further information about Edith Nesbit can be found here: The Edith Nesbit Society

Books associated with this article