Private passions and Italian families

Stefania Ciocia takes a sideways look at Dante

I was eight years old when my paternal grandfather died, my first experience of loss in the family. I don’t have many memories of him, and those I have probably been layered with stories I’ve since heard about him. I remember nonno Ettore as a tall, lean and very serious man. The perceived tallness, it turns out, was definitely in my child’s eye. My unreliable recollections measure him up against my other grandfather, nonno Alberto, who was twelve years younger and whose loving presence in my life I got to enjoy for much longer. Alberto was tall, but he was also broader, and larger than life in other ways: always telling jokes, fond of banter, on first name terms with all the shopkeepers in the neighbourhood. Grandma was a homebody, so he was in charge of daily foraging trips for bread from the baker’s rudimentary counter (the heart of the operation was backstage, in the oven), fresh fruit from Mimmo the greengrocer, and the sports newspaper. En route he would often stop at the local coffee bar, not so much for an espresso, but for a bit of good-natured teasing with the all-male staff, who supported a rival football team to his own.

He wore his heart on his sleeve, nonno Alberto: easily moved to tears, gregarious and easy-going. Nonna Gina (short for Regina, a queen in name and in deed) was the disciplinarian in the family, a ‘carabiniere’, the no-nonsense matriarch ruling the household. She wasn’t expansive in her demonstrations of affection, but she’d turn a blind eye when my brother and I would help ourselves to a piece of fried artichoke, still hot from the pan, as a cheeky advance of the lavish Sunday lunch to come. I’d never taste again carciofi fritti like those, stolen while still soaking with oil on their bed of kitchen roll, and seasoned with nonna Gina’s indulgence.

The good-cop / bad-cop roles were reversed with my paternal grandparents. Nonna Anna was kindness personified, gentle and genteel, infinitely patient with my brother and me. She must have read us our favourite stories ad nauseam, impervious to the repetitiveness of the task, happy to share in our childish enthusiasms. One of them was the ritual of playing with the ‘scatoloni’, big cylindrical containers of bumper quantities of laundry powder. My Mum had repurposed a couple of them – duly covered in colourful wrapping paper – as boxes for our miscellaneous plastic toys, which would tumble out loudly and with a faint smell of detergent. That noisy incipit was the best bit, an opener more exciting than any game we could play with the giant construction blocks and other knickknacks, my brother and I on the big Tunisian rug, and nonna Anna watching the whole performance from the green sofa.

The good-cop / bad-cop roles were reversed with my paternal grandparents. Nonna Anna was kindness personified, gentle and genteel, infinitely patient with my brother and me. She must have read us our favourite stories ad nauseam, impervious to the repetitiveness of the task, happy to share in our childish enthusiasms. One of them was the ritual of playing with the ‘scatoloni’, big cylindrical containers of bumper quantities of laundry powder. My Mum had repurposed a couple of them – duly covered in colourful wrapping paper – as boxes for our miscellaneous plastic toys, which would tumble out loudly and with a faint smell of detergent. That noisy incipit was the best bit, an opener more exciting than any game we could play with the giant construction blocks and other knickknacks, my brother and I on the big Tunisian rug, and nonna Anna watching the whole performance from the green sofa.

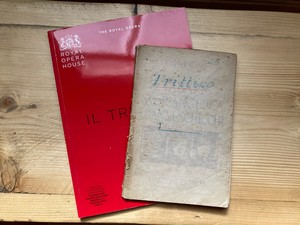

Nonno Ettore was still alive then, but babysitting was not his bag. He was made of sterner stuff, the Homeric name alone conjuring up notions of heroism, integrity and zeal. To this day I associate him with his two abiding passions, though I was probably only aware of the one way back when: opera. He played it often, and he played it loud, because music was best appreciated at the volume at which one’d listen to a performance at La Scala. Never mind that he and grandma lived in an apartment, and not in a theatre. Luckily for the neighbours, nonno Ettore’s other great love was The Divine Comedy, which could be enjoyed more quietly. He had several copies of it, including a massive volume with Gustavo Doré’s illustrations, and a tiny pocket edition, printed on onionskin paper. We still have it at home in Italy. I’ve often looked at it, fascinated by the minuscule annotations in pencil in nonno Ettore’s neat handwriting.

I must ask if I can have it next time I visit Dad, who is very unsentimental about such things. He is also a contrarian, which must be the reason why he has grown up with with a visceral dislike both of opera and of The Divine Comedy. The former aversion does sadden me a bit now. Nonno Ettore’s passion skipped a generation, with some delay and variations on the theme; I got the operatic bug later in life and, by all accounts, my tastes are different from my grandfather’s. My gateway to opera was Giacomo Puccini who, according to Dad, was a bit too modern for nonno Ettore, a Verdi man through and through. My Dad can’t stand either composer, which is a shame because I’d love to swap notes with him on my belated musical enthusiasms.[1]

I must ask if I can have it next time I visit Dad, who is very unsentimental about such things. He is also a contrarian, which must be the reason why he has grown up with with a visceral dislike both of opera and of The Divine Comedy. The former aversion does sadden me a bit now. Nonno Ettore’s passion skipped a generation, with some delay and variations on the theme; I got the operatic bug later in life and, by all accounts, my tastes are different from my grandfather’s. My gateway to opera was Giacomo Puccini who, according to Dad, was a bit too modern for nonno Ettore, a Verdi man through and through. My Dad can’t stand either composer, which is a shame because I’d love to swap notes with him on my belated musical enthusiasms.[1]

As to Dad’s antipathy for Dante, I find it amusing, a lesson in earthly contrappasso (the Dantesque concept of retribution): cajoled as a child to learn passages from the Commedia by heart, Dad is now completely allergic to it. I like to think that Dante would have understood. In my previous blog, I mentioned his extraordinary ability to engender sympathy for those very same characters he confines to Hell, and I promised to return to this subject. It seems appropriate to be writing this piece during Holy week, since that’s when the pilgrim Dante goes on his journey through the three realms of the afterlife. The beginning of the poet’s otherworldly adventure is usually understood to be 25 March 1300, and on that day this year – renamed Dantedì to mark the 700th anniversary of his death – there have been many celebrations in Italy and around the world.

The Italian festivities have been marred – or livened up, depending on points of view – by an alleged slight on Dante by the German literary critic Arno Widmann who, in an article in the Frankfurter Rundschau, has accused our national poet of being a social-climber and a plagiarist, while arguing that his writing is not as readily accessible to contemporary Italian readers and as influential on our language as Shakespeare’s is on Anglophone culture. The claim about Dante’s relevance and literary stature would have been enough to get my compatriots up in arms; in the predictable ensuing media storm, various public figures have reinvented themselves as literary experts. The prize for best intervention goes to Dario Franceschini, the Minister of Culture, who tweeted “Non ragioniam di lor ma guarda e passa” (“Let us not speak of them, but look, and pass”, Inf. III, 50), a line from The Divine Comedy so famous to have become a common saying in Italian (so much for Dante’s irrelevance, Signor Widmann).[2]

I love the irony of uttering this line while essentially keeping the diatribe going. Nobody likes a controversy and does outrage quite like us Italians. It’s part of our national character to enjoy a good argument, the more pointless the better. It can never be said that we’d let an opportunity to make noise go to waste. It’s all part of the fun. And in that sense the article in the Frankfurter Rundschau is the gift that keeps on giving, because the bone of contention has morphed from Widmann’s alleged claims to the way in which they have been reported, and possibly mistranslated, by the Italian press. Needless to say, my father has remained singularly unbothered by the whole kerfuffle, with or without this meta-dimension. Or rather, he has been bothered only in so far as Dante has clogged up the airwaves on a week when there was more than enough of him already for Dad’s liking.

I love the irony of uttering this line while essentially keeping the diatribe going. Nobody likes a controversy and does outrage quite like us Italians. It’s part of our national character to enjoy a good argument, the more pointless the better. It can never be said that we’d let an opportunity to make noise go to waste. It’s all part of the fun. And in that sense the article in the Frankfurter Rundschau is the gift that keeps on giving, because the bone of contention has morphed from Widmann’s alleged claims to the way in which they have been reported, and possibly mistranslated, by the Italian press. Needless to say, my father has remained singularly unbothered by the whole kerfuffle, with or without this meta-dimension. Or rather, he has been bothered only in so far as Dante has clogged up the airwaves on a week when there was more than enough of him already for Dad’s liking.

With apologies to my father, I’d like to offer here my own modest homage to The Divine Comedy by highlighting a couple of its most moving passages. The place to start from is Canto V of Inferno, the second circle of Hell, where the lustful are swept around by an eternal whirlwind, just as in life they were prey to uncontrollable passions. Dante and his guide Virgil spot a number of mythological and historical figures in the storm – Cleopatra, Helen of Troy, Tristan, and Dido, amongst others – but the pilgrim’s curiosity is stirred by a couple who “seem upon the wind to be so light” (75). They are two near contemporaries of Dante’s, Paolo and Francesca. He asks to hear their story, and the woman obliges, providing an eloquent exposition of the doctrine of courtly love in three tercets of such stunning beauty that I wouldn’t dream of paraphrasing them:

“Amor, ch’al cor gentil ratto s’apprende, “Love, that on gentle heart doth swiftly seize,

prese costui de la bella persona. Seized this man for the person beautiful

che mi fu tolta; e ’l modo ancor m’offende. That was ta’en from me, and still the mode offends me.

Amor, ch’a nullo amato amar perdona, Love, that exempts no one beloved from loving,

mi prese del costui piacer sì forte, Seized me with pleasure of this man so strongly,

che, come vedi, ancor non m’abbandona. That, as thou seest, it doth not yet desert me;

Amor condusse noi ad una morte. Love has conducted us unto one death;

Caina attende chi a vita ci spense.” Caina waiteth him who quenched our life!”

Queste parole da lor ci fuor porte. These words were borne along from them to us.[3]

Profoundly touched by this speech, Dante wants to know how the two fell in love. This further request prompts from Francesca the very human consideration that there is no greater pain than to remember happiness in time of sorrow. Nonetheless, she recounts that she and Paolo had been reading together of how Launcelot had been enthralled by love (for Guinevere, King Arthur’s wife – another touchstone of courtly passion). Alone with each other, they had been following the story, without malice, until the point when Launcelot kisses his beloved: “Galeotto [a go-between] was the book and he who wrote it. / That day no farther did we read therein” (137-38). While Francesca is talking, Paolo weeps. Dante is so affected by the scene that, he says, “I swooned away as if I had been dying, / And fell, even as a dead body falls” (141-42). Thus ends the canto, with a double affirmation of the intensity of emotion that storytelling can provoke in us.[4]

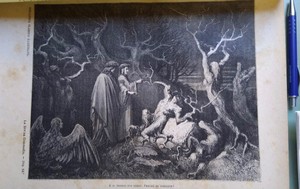

The power of words is reiterated in Dante’s later encounter with Pier delle Vigne, Frederick II’s closest counselor, who lost the emperor’s trust when he was targeted by false rumours. He is one of the sinners in the second ring of the seventh circle of Hell, where those who have committed violence against themselves have been turned into barren, knotted trees.[5] Dante finds out about this transformation abruptly because, when he cannot fathom the source of the moans and cries in what looks like a deserted forest, he is invited by Virgil to tear a twig from a branch.[6] “Why dost thou mangle me?” (Inf. XIIII, 33) complains the tree, bleeding from the cut and ill-disposed towards his unwitting offender. Virgil intervenes to sweet-talk Pier delle Vigne into telling his story, suggesting that it might restore his reputation. The damned is won over by Virgil’s kind entreaty and explains how he came to his doom: “My spirit, in disdainful exultation, / Thinking by dying to escape disdain, / Made me unjust against myself, the just” (70-2). After this revelation, Dante is once more lost for words. He – and we – must rely on Virgil to continue the conversation with the soul who had once “both keys had in keeping / Of Frederick’s heart” (58-9).

The power of words is reiterated in Dante’s later encounter with Pier delle Vigne, Frederick II’s closest counselor, who lost the emperor’s trust when he was targeted by false rumours. He is one of the sinners in the second ring of the seventh circle of Hell, where those who have committed violence against themselves have been turned into barren, knotted trees.[5] Dante finds out about this transformation abruptly because, when he cannot fathom the source of the moans and cries in what looks like a deserted forest, he is invited by Virgil to tear a twig from a branch.[6] “Why dost thou mangle me?” (Inf. XIIII, 33) complains the tree, bleeding from the cut and ill-disposed towards his unwitting offender. Virgil intervenes to sweet-talk Pier delle Vigne into telling his story, suggesting that it might restore his reputation. The damned is won over by Virgil’s kind entreaty and explains how he came to his doom: “My spirit, in disdainful exultation, / Thinking by dying to escape disdain, / Made me unjust against myself, the just” (70-2). After this revelation, Dante is once more lost for words. He – and we – must rely on Virgil to continue the conversation with the soul who had once “both keys had in keeping / Of Frederick’s heart” (58-9).

In these two episodes, words exculpate and accuse, seduce and injure. An even greater contrast is to be found between Dante-the-character and Dante-the-writer: the one, overwhelmed by pity, is rendered incapable of speech, while the other bestows literary immortality through his epic poem. And so it is that Pier delle Vigne gets his posthumous rehabilitation, and Paolo and Francesca ascend to the pantheon of legendary lovers that includes those famous figures who had preceded them in their canto. The story of Paolo and Francesca has been celebrated by several artists, including the pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriele Rossetti, the Romantic poet Leigh Hunt and the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninov.

The most glorious case of artistic redemption based on The Divine Comedy, however – sorry, Dad – is in one of Puccini’s later, and lesser-known, works, Il Trittico, a tryptic of one-act operas which takes us from the dark, hopeless tragedy of ‘Il tabarro’ (‘The cloak’) through the heart-wrenching, redemptive melodrama of ‘Suor Angelica’ (‘Sister Angelica’) to the uplifting, life-affirming comedy of ‘Gianni Schicchi’. The twist in the tale is that the eponymous protagonist of the final part of the sequence is taken straight from the depths of Hell, where he makes a brief appearance in Canto XXX. Schicchi is amongst the fraudulent for his most egregious crime: impersonating the deceased Buono Donati in order to forge his will. We barely see Schicchi in Inferno, and we don’t hear from him at all; he is too busy fighting with a fellow sinner to talk to us.

Puccini takes this minor, silent character in The Divine Comedy, and turns him into a lovable scoundrel, who does defraud the Donatis but for an extremely good cause. The Donatis are a venal, self-interested, hypocritical bunch, who have been waiting eagerly for Buono’s demise in order to cash in the inheritance. Florentine born-and-bred, they look down on the likes of Schicchi, a self-made man from the Tuscan countryside; the matriarch, Zita, won’t grant Rinuccio, her nephew, permission to marry Lauretta, Schicchi’s dowry-less daughter. Schicchi will save the day by turning Buoso’s most precious possessions over to himself, making it possible for the young lovers to marry. In this delightful light opera Puccini gives us a picture of Italian families at their worst and at their best: the Donatis’ cacophonous squabbling, the love-birds’ dreams of a spring wedding and Schicchi’s ingenuity, fuelled by paternal affection, yield vibrant ensemble singing, sweet duets and an all-time favourite aria in Lauretta’s ‘O mio babbino caro’.

At the end of the opera, Dante himself gets a playful tribute. In a brief spoken epilogue, Gianni Schicchi breaks the fourth wall, asking the audience whether Buoso’s money could have ended in better hands. Then he adds: “For this prank, I’ve been sent to Hell…and so be it; but with our great father Dante’s permission, if this evening you’ve had fun, I entreat you to grant me [he claps] extenuating circumstances”. I know I’m biased, but isn’t this the most joyous, immersive example of redemption through art? Minutes earlier, in the last exquisite duet of the piece, Rinuccio and Lauretta have seen their future and its possibility spreading ahead of them. They look over Fiesole, on the outskirts of the city, where they had their first kiss. Together, they reminisce: “Florence, from afar, looked like Paradise to us”.

At the end of the opera, Dante himself gets a playful tribute. In a brief spoken epilogue, Gianni Schicchi breaks the fourth wall, asking the audience whether Buoso’s money could have ended in better hands. Then he adds: “For this prank, I’ve been sent to Hell…and so be it; but with our great father Dante’s permission, if this evening you’ve had fun, I entreat you to grant me [he claps] extenuating circumstances”. I know I’m biased, but isn’t this the most joyous, immersive example of redemption through art? Minutes earlier, in the last exquisite duet of the piece, Rinuccio and Lauretta have seen their future and its possibility spreading ahead of them. They look over Fiesole, on the outskirts of the city, where they had their first kiss. Together, they reminisce: “Florence, from afar, looked like Paradise to us”.

I have always loved this final duet, so full of youthful hope and innocence. That, and Puccini’s sublime orchestration, are enough to bring tears to my eyes, but of late that final line opens the floodgates. The pandemic has exiled me from Italy, and from my Italian family. In entwining my private passions and personal reminiscences with my literary reflections, I hope to have entertained you; but if I have digressed too much, dear readers, consider my nostalgia for Italy, and grant me extenuating circumstances.

Dr Stefania Ciocia is a proud immigrant, who made a home in the U.K. twenty-odd years ago. She is a Reader in Modern and Contemporary Literature at Canterbury Christ Church University. You can find her on Twitter as Gained in Translation @StefaniaCiocia.

Main image: Gustave Doré, Dante and Virgil in the Ninth Circle of Hell, The Divine Comedy painting, 1861 Credit: Incamerastock / Alamy Stock Photo

Top Left: Alberto e Gina Top Right: Anna e Ettore Middle Left: Nonno’s Libretto and mine Middle Right: Doré’s Pier delle Vigne from Ettore’s copy of the Commedia Bottom: Lucio Gallo as Schicchi in the Royal Opera House 2011 production of Il Trittico

[1] Dad enjoys classical music provided it involves no singing, with the sole exception of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. I have no formal musical education to speak of, and it took me years to branch out beyond Puccini, who remains a firm favourite of mine. My other great operatic love is Handel, whose back catalogue will keep me busy for a while longer. I wonder what nonno Ettore would make of his grand-daughter’s patchy, self-taught musical knowledge. I operate on instinct alone, in pursuit of that ecstatic feeling that certain compositions trigger in me. I know it when I hear it. I can honestly say that this ongoing journey of discovery is a marvellous source of pleasure in my life.

[2] Virgil utters these words to Dante – a cue for him not to ask any more questions on the matter – as a sign of his contempt for the pusillanimous, those “who lived withouten infamy or praise” (Inf. III, 36; another phrase that has entered common parlance). They are the first group of damned whom Dante and Virgil encounter in Hell. Those guilty of moral apathy are not even worthy of Hell proper; they are not assigned to one of its nine circles but can be found just beyond the infernal gate. They will spend eternity running naked after a flag (contrappasso for being unable to commit to a cause in life) while being stung by wasps and hornets. The translation I am using for this blog is Henry Wadsworth Longefellow’s.

[3] Inferno, V, 99-108. The anaphora (repetition of “Love” at the beginning of each stanza) is but the most obvious sign of Francesca’s rhetorical skills; it is often noted that she is careful to emphasise her role as innocent victim of external forces: love, Launcelot’s story, Paolo’s passion, her husband’s revenge. Although it is Francesca who speaks, line 108 attributes her words to Paolo too, for even in death they are as one. Francesca da Rimini was forced into a marriage of convenience with the much older, unattractive Gianciotto Malatesta, Paolo’s brother. On his death – yet to happen at the time of composition of The Divine Comedy – Gianciotto will end up in Caina for killing the adulterous lovers. “Caina” (after Cain) is the place in the ninth circle of Hell reserved for those who betrayed their family members, as Gianciotto did with the murder of his wife and brother.

[4] I love the reversal of traditional gender roles: Francesca tells us of the strength of her feelings, Dante shows us by fainting.

[5] Although the historical sources are far from unanimous on the matter, according to Dante Pier delle Vigne was driven to suicide. The punishment for violence against oneself is meant to reflect the sinner’s lack of respect for the human form. Pier delle Vigne’s gnarly trunk also reflects his elaborate, tortuous syntax, as befits a man of law.

[6] Virgil’s cruel suggestion is Dante-the-poet’s opportunity to pay homage to his guide’s famous epic poem. In Book III of the Aeneid, blood comes out of a shrub whose branches Aeneas has been gathering for a sacrifice. The shrub has grown on the place where Polydorus, Priam’s youngest son, was treacherously killed, as the voice of the dead Trojan prince explains to Aeneas, while begging for a proper burial. When Dante is shocked by the talking-and-bleeding tree, Virgil tells him off for not remembering Polydorus’s story from the Aeneid.

Books associated with this article

The Divine Comedy

Dante Alighieri