The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

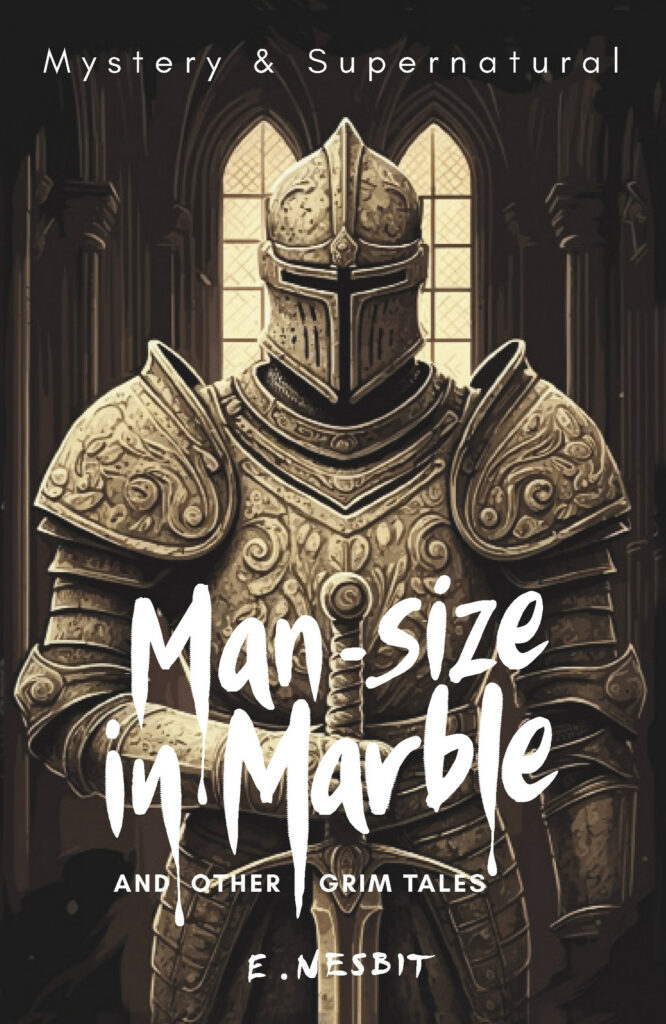

Denise Hanrahan Wells looks the supernatural short stories of Edith Nesbit, now available in our new publication Man-size in Marble and Other Grim Tales The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

Chances are, many readers know Edith Nesbit from her creation of courageous Bobbie in the successfully adapted 1905 novel The Railway Children. Or, possibly your first introduction was through the mysterious creature the Psammead in Five Children and It (1902), or perhaps the adventures of Jerry, Jimmy and Kathleen in The Enchanted Castle (1907). Therefore, some may be surprised to find images such as the following, flowing from the same pen:

… So he went upstairs, and at the door of the first bedroom he came to he struck a wax match, as he had done in the sitting rooms. Even as he did so, he felt that he was not alone. And he was prepared to see something but for what he saw he was not prepared. For what he saw lay on the bed, in a white loose gown – and it was his sweetheart, and its throat was cut from ear to ear.

This excerpt comes from Nesbit’s short story ‘The Mystery of the Semi-Detached’ included in her 1893 collection Grim Tales. In just a few lines she moves from creating a vague sense of unease to a startling shock. To say this is characteristic of Nesbit’s gothic writing is an oversimplification as she wrote many and varied short stories which could be categorized under the umbrella of horror. Whilst there are distinct similarities regarding some aspects of style and thematics across her tales, there is also a rich variety and this sense of variety is exemplified by the newly published Wordsworth Edition Man-size in Marble and Other Grim Tales.

Nesbit is not alone in being better known for other forms of writing, despite producing a significant amount of material in the horror genre. Writers such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, Edith Wharton, Henry James and E.F. Benson all had notable forays into the realms of gothic despite being more usually associated with other forms of writing.[i] Yet Nesbit wrote a large number of horror stories during the course of her writing career, although it is sometimes wrongly assumed this was simply something she did until her children’s stories made her famous. Her horror works span from the late Victorian era of the 1880s up until the post First World War period, with her final story ‘The Detective’ appearing in 1920. The Shadowy World of Edith

Many of her stories made their first appearance in popular journals of the day such as Longman’s Magazine, Temple Bar, Windsor, and London Magazine. The Strand Magazine, famous for its longstanding publication of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, also published many of Nesbit’s tales. She collected some of her short stories together in several volumes, beginning with the previously mentioned Grim Tales and Something Wrong in 1893. The Wordsworth Edition of her tales is unusual as it not only reproduces the Grim Tales collection in its entirety, but also includes all of her other horror stories, many of which have previously been overlooked.

Stephen Carver’s Introduction to the collection discusses how biographies and other secondary writings about Nesbit’s work tend to focus on her children’s fiction, whilst her horror stories tend to be dismissed. The Radio 4 programme Great Lives devoted an episode to Edith Nesbit on 22 April 2024. She was chosen by children’s writer Katherine Rundell who praised her for continuing to inspire children’s fiction today. Biographer Elisabeth Galvin joined the discussion and posited that Edith began writing through necessity as a young mother in order to help support the family. At that time her husband Hubert Bland was very ill, almost dying from smallpox. To compound matters his business collapsed when his partner absconded to Spain with all of their money. Thus, she would sit up late into the night writing what Galvin described as ‘her hack stories for newspapers.’ Galvin is not alone in viewing Nesbit’s gothic work in this way and it is difficult to ignore the negative connotations imbedded in such a term. The word ‘hack’ originates from Hackney Carriage, a form of transport available for hire. Thus a ‘writer for hire’, namely someone who produces large amounts of writing quickly to earn money, may well be viewed in negative terms. Similarly, genre fiction, for example horror and science fiction may also be dismissed as being popular, not highbrow or literary and thus unlikely to be art or to put forward important ideas. Clearly, this is a rather traditional, and some may say outdated stance, but may well explain why Nesbit’s horror stories have attracted little critical attention. A few of her stories have been anthologised over the years, most commonly ‘Man-size in Marble’ as well as ‘John Charrington’s Wedding’ and ‘The Ebony Frame’. The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

Stephen Carver’s Introduction to the collection discusses how biographies and other secondary writings about Nesbit’s work tend to focus on her children’s fiction, whilst her horror stories tend to be dismissed. The Radio 4 programme Great Lives devoted an episode to Edith Nesbit on 22 April 2024. She was chosen by children’s writer Katherine Rundell who praised her for continuing to inspire children’s fiction today. Biographer Elisabeth Galvin joined the discussion and posited that Edith began writing through necessity as a young mother in order to help support the family. At that time her husband Hubert Bland was very ill, almost dying from smallpox. To compound matters his business collapsed when his partner absconded to Spain with all of their money. Thus, she would sit up late into the night writing what Galvin described as ‘her hack stories for newspapers.’ Galvin is not alone in viewing Nesbit’s gothic work in this way and it is difficult to ignore the negative connotations imbedded in such a term. The word ‘hack’ originates from Hackney Carriage, a form of transport available for hire. Thus a ‘writer for hire’, namely someone who produces large amounts of writing quickly to earn money, may well be viewed in negative terms. Similarly, genre fiction, for example horror and science fiction may also be dismissed as being popular, not highbrow or literary and thus unlikely to be art or to put forward important ideas. Clearly, this is a rather traditional, and some may say outdated stance, but may well explain why Nesbit’s horror stories have attracted little critical attention. A few of her stories have been anthologised over the years, most commonly ‘Man-size in Marble’ as well as ‘John Charrington’s Wedding’ and ‘The Ebony Frame’. The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

Elisabeth Galvin’s biography of Nesbit does make mention of her horror stories, and unusually finds value in them, a position with which I agree. Galvin suggests they originate from the mind of someone who was unhappy, and if you follow the details of her life, this may well seem true. However, she states Nesbit should be ‘applauded for her pioneering ghost stories that were several degrees chillier than anything that had been written before.’[ii] Nesbit does indeed develop a considerable amount of chill in her stories. Whilst there are some similarities and recurring images, there are distinct differences too. Sometimes there is a logical explanation for what initially appeared to be supernatural, other times the horror is unapologetically supernatural in origin. Unusually for a lady writer of the time, many of her narrators are male, and not all of them are heroic. The Wordsworth collection nicely exemplifies the range of her horror writing. A few of the stories are quite humorous and playful, offering a little light relief from the darkly gothic tales, not all of which have happy endings. Other stories defy expectations such as ‘The Haunted House’ first published in The Strand Magazine in 1913. As its name suggests, this starts out as a haunted house tale, whereby the male protagonist answers an advertisement to investigate strange phenomena and arrives ‘in front of a white house with bare, gaunt windows.’ However, this is a story which shifts the ground beneath the reader as the narrative progresses. How? Well, you will need to read it to find out.

As previously noted, genre fiction is frequently dismissed as being purely for entertainment purposes and thus of little value. However, gothic/horror fiction has provided many writers the means with which to explore difficult, and at times, controversial topics. Nesbit’s horror stories are no exception. Many of her stories have at their centre the problematic relationships people can have with each other. Rather than the sanctity of the domestic interior of the home functioning as a safe space, in Nesbit’s stories the protagonist may well find the home a place of danger, where threats emanate from unearthly and sometimes unmentionable sources. Galvin praises her stories for ‘their concise turn of phrase, genuinely horrible plotlines and gruesome conclusions.’ Nesbit’s story ‘The Portent of the Shadow’ indeed ticks all of these boxes and more. Possibly there is some working through of issues surrounding her own domestic situation, but the story also highlights the limited opportunities available for the unmarried woman and the subsequent unfulfilled lives some of these women were forced to live. The opening lines of the story demonstrates the power of her prose as well as providing an intriguing beginning:

This is not an artistically rounded off ghost story, and nothing is explained in it, and there seems to be no reason why any of it should have happened. But that is no reason why it should not be told. You must have noticed that all the real ghost stories you have ever come close to, are like this in these respects – no explanation, no logical coherence. Here is the story.

The direct address from the first person narrator establishes a relationship with the reader and draws us in by making us want to know what the story is. The narrator is female and we learn she intends to tell us about the night of a dance at Christmas time, and as we all know, Christmas is the perfect time for ghost stories. There is a long-established tradition of seasonal ghost stories, for example, the special Christmas edition of the Dickens conducted journal Household Words, featuring ghost stories from the likes of Elizabeth Gaskell. In the 20th Century we had the 1970s BBC TV A Ghost Story for Christmas, and most recently, the Mark Gatiss ‘A Woman of Stone’ adaption of Nesbit’s ‘Man-size in Marble’. The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

The narrator of ‘The Portent of the Shadow’ is one of three girls staying over at her Aunt’s large country house and they begin to amuse themselves by telling ghost stories against the backdrop of ‘the whisper of the wind in the cedar branches, and the scraping of their harsh fingers against our window panes.’ Are you already feeling a slight chill?

Their amusement is interrupted by a tap at the door which begins to open slowly and our narrator tells ‘… the instant of suspense that followed is still reckoned among my life’s least confident moments.’ Fortunately, the visitor is only her Aunt’s housekeeper Miss Eastwich, ‘the most silent woman’ she has ever known. To her horror, the youngest and most reckless of the girls invites Miss Eastwich to join them for cocoa and ghostly tales. This makes way for that typically gothic device of a story within a story, as with some persuasion and much protestation, the mysterious Miss Eastwich begins her tale.

Twenty years ago, her two best friends, whom she loved ‘more than anything in the world’ married each other. Our original young narrator interrupts to ensure we notice the subtext of Miss Eastwich’s apparent unrequited love for the husband. Miss Eastwich continues her story of how he wrote asking her to visit their new home, The Firs, as he was concerned for his wife’s health, and because the gloom of the house was making him feel gloomy. The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

The house is situated in Lee, close to London, a place Nesbit herself lived for a while during her married life. This will not be a typical haunted house tale though because, as Miss Eastwich reveals, twenty years ago ‘there were streets and streets of new villa-houses growing up round old brick mansions’, so how can a new house be haunted? On arrival, the house exhibits none of the gloom indicated in the letter and Miss Eastwich finds it ‘warm and welcoming.’ And yet there are early indications of something wrong as, at several points, Miss Eastwich is reluctant to continue her story and has to be encouraged to continue. She does continue though, and notes her surprise on finding the wife Mabel quite well, whereas it is the husband who looks strained and unwell. After dinner, Mabel retires to bed and they are left alone, allowing Miss Eastwich, who we now learn is named Margaret, to encourage her friend to tell his troubles. What can possibly be wrong with a bright new home in which they are the first to live? Yet Nesbit creates a distinct sense of unease despite Margaret’s logical persona. Her friend tells of an unexplained feeling:

…I can’t describe it – I’ve seen nothing and I’ve heard nothing, but I’ve been so near to seeing and hearing, just near, that’s all. And something follows me about – only when I turn round, there’s never anything, only my shadow.

Margaret immediately dismisses his fears, putting it down to overwork. Yet, it is not long before Margaret also begins to experience similar feelings of unease, despite her best efforts to put it down to her imagination being affected by his repeated insistence of being haunted. She notes how particularly on stairs and in passageways ‘there was always something behind me;’ but on turning around it ‘drooped and melted into my shadow.’ This dark, mysterious, shadowy presence continues throughout her stay until her tale reaches a dramatic climax, and more. But I am afraid you will need to read the story to find out what happens.

In addition to being one of Nesbit’s most atmospheric and creepy tales, there is a fair amount of subtext beneath the gothic surface. For one thing, Miss Eastwich’s close friendship with both husband and wife (with the clear message she harboured more than friendly feelings towards the husband) is a little reminiscent, but a more respectable version of Nesbit’s own household situation. This household consisted of Edith Nesbit and husband Hubert Bland, their three children, as well as Nesbit’s friend Alice Hoatson and her two children also fathered by Bland.

The plight of Miss Eastwich also functions to draw attention to the lack of opportunities available to unmarried women. During her youth the two friends were all she had in the world. Twenty years later, the only option open to her is to be a ‘housekeeper, companion and general stand-by’ and clearly her life is not a happy one. At the beginning of the story the original young narrator tells us ‘how her persistent silence had built a wall around her’ leading them ‘to treat her as a machine.’ Miss Eastwich’s joyful response to the welcome offered by the other girls makes the narrator realise she had never really noticed her and reflects it ‘did not please me to think that at the cost of cocoa, a fire, and my arm around her neck, I might have heard this new voice any time these six years.’ It becomes clear just what a dreary, neglected and overlooked position Miss Eastwich and many other housekeepers like her were forced to adopt.

Other stories in the collection offer a nod towards changing times. ‘A Perfect Stranger’ first published in Windsor Magazine in 1899 features a young female protagonist Alexa, who appears to be an independent modern woman as she has a bicycle. Indeed, we are told ‘now since she had a bicycle, all things seemed possible.’ Changing times are even more apparent as Nesbit’s stories move into the twentieth century. ‘The Violet Car’ (1910) features a haunting with a difference, as this story involves the modernity of a motor car. The narrator of this story tells us she is a nurse and again exhibits a reluctance to tell her tale but emphatically says ‘These things happened.’ Our nurse narrator has travelled from London to start a new job and finds herself stranded at the station as no carriage has been sent to meet her. A fellow passenger informs her she has a car coming to collect her and offers her a ride. The novelty of the vehicle is evident from her descriptions which refer to it moving ‘like magic’ and she tells of how as they ‘drove through the dark – I could hear the wind screaming, and the wild dashing of the rain against the windows, even through the whirring of the machinery.’ The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

One of the strengths of this story is the degree of mystery and uncertainty created by the narrator. She has been engaged by Mr and Mrs Eldridge, and is somewhat mystified when she finds herself alone with each of them in turn. She had initially been engaged by Mr Eldrige to care for his wife whom he describes as ‘slightly deranged.’ Yet Mrs Eldridge says it is her husband who is ill and needs caring for. It becomes increasingly difficult to know who to believe and yet, of one thing she becomes certain: ‘… that with these two fear lived. It looked at me out of their eyes.’ This story, like others in the collection, maintains a level of suspense until the concluding lines, and as you may gather from the title, the car will be significant in the unfolding of the tale.

Not all of the tales are as creepy as the ones I have discussed. Whilst many are filled with suspense, some tales are more in the mystery vein and there is also a little light relief. The collecting together of well-known as well as some less familiar stories will hopefully work towards establishing Edith Nesbit’s place amongst the canon of classic horror writers. Settle down and read if you dare…

Denise Hanrahan Wells

The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit

[i] The gothic works of all of these writers are available in Wordsworth’s Mystery and Supernatural series

[ii] See Elisabeth Galvin, The Extraordinary Life of E. Nesbit: Author of Five Children and It, Chapter 10 ‘Living Well’

Main image: Tombs in Templars’ Church, London. Credit: Robert Harding / Alamy Stock Photo

Our edition of Man-size in Marble and Other Grim Tales, on sale for £4.99, can be found here: Man-size in Marble and Other Grim Tales – Wordsworth Editions

Further information about Edith Nesbit can be found here: The Edith Nesbit Society

The Shadowy World of Edith Nesbit