‘There was no possibility of taking a walk that day’[1]

To celebrate midwinter, Sally Minogue looks at some of the ways writers have drawn inspiration from winter weather.

As I write, I’m looking out over a perfect winter landscape. The Frost has performed its secret ministry. In the hoar-laden grass near to my window, chaffinch, goldfinch and other small birds bend busily to seed fallen from the feeder; 23 in one count, but it varies as they flock suddenly out and flock in again. Blue-tits hop niftily looking for tiny spiders or tiny somethings on a sage bush, each leaf iced white, its etiolated stems bending under even their small weight. Chickens peck up scraps of suet and mealworms thoughtfully placed; the blackbird, always on the qui vive, was searching there earlier, having already remarked the place of yesterday’s small harvest. The pond is only lightly frozen; the small forest of hardy kale in the veg garden beyond is dusted with frost but we’ll have good pickings from it later.

In the distance spreads Radnorshire, with its mixed landscape of hills, fields, hedges and stands of trees, both deciduous and evergreen. It is a high landscape but a domestic one, the fields small in scale and irregular of pattern to reflect both the physical contours and the distribution of the land across small farms. I can’t see the sheep but they are there. This is hard-won farming, right on the margins; but what it presents to the eye is most pleasing in this very human patched world, while the height above sea level brings out the natural nobility of the rolling hills.

So I am not at my usual writing table, but lucky to be spending the New Year with my family in the Welsh Marches. A few days ago we were up to our ankles in mud (if we could stay upright) and the wind was tearing out ancient doughty hawthorn trees by their roots. But today all is stillness and sombre beauty. I’m aware that I haven’t yet started talking about any particular books; but I wanted to lay the scene because it reminds me of how and why writers take such inspiration from even a bleak landscape. My intended subject in this blog was the dreariness of January and how that has figured in classic writing, both poetry and prose. But instead I have been reminded of the grandeur that winter can bring, as well as the delicacy with which it can repaint and repoint a familiar view.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

I have already indirectly quoted the first lines of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s great poem, ‘Frost at Midnight’: ‘The Frost performs its secret ministry, / Unhelped by any wind’.[2]

The poet moves quickly from the scene outside to that within, first reflecting on the movement of the fire’s flames:

…the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Looking at our log-burner here, I see that same familiar film of bluish flame, so intangible, mysterious and absorbing. For Coleridge, it takes him back to boyhood days staring into a similar fire, and thus into a description of that past time and the dreams he wove within the glancing flame. This in turn takes him to what is perhaps the central subject of the poem, the baby in the cradle beside him, a sleeping innocent

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the interspersèd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought.

My babe so beautiful! It thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee…

The poem ends with the baby’s imagined future, brought up as he will be amongst ‘Sea, hill and wood’, ‘the lovely shapes and sounds intelligible / Of that eternal language, which thy God /Utters’. ‘Therefore’, he prophesies, ‘all seasons shall be sweet to thee’, whether summer or winter. Thus the poem neatly ends where it began, but now in the baby’s future rather than the poet’s present:

Whether the eaves-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

I have spent some time on Coleridge’s poem because it is a perfect example of the way a poet can take a natural scene – frost at midnight, as announced simply by the title – and draw from it such depths and distances. The poem manages to be both intimate, creating a cocoon for the poet and baby by the fire while the frost transforms the world outside, and visionary as the passage starting with the address to the ‘Dear Babe’ ends with:

That eternal language which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

It also, in classic Romantic mode, transcends the barriers of time, going back to the poet’s own childhood and forward to his child’s adulthood, at the same time moving both inward to the writer’s nostalgic thoughts and memories and outward to eternal nature and its connection to a benign Creator. But crucial to the harmony of the whole and to the poem’s rootedness in a particular reality is that one anthropomorphic but accurate image of the Frost’s ‘secret ministry’. It makes us look at the frozen world and its relationship to us in quite a different way.

……………..

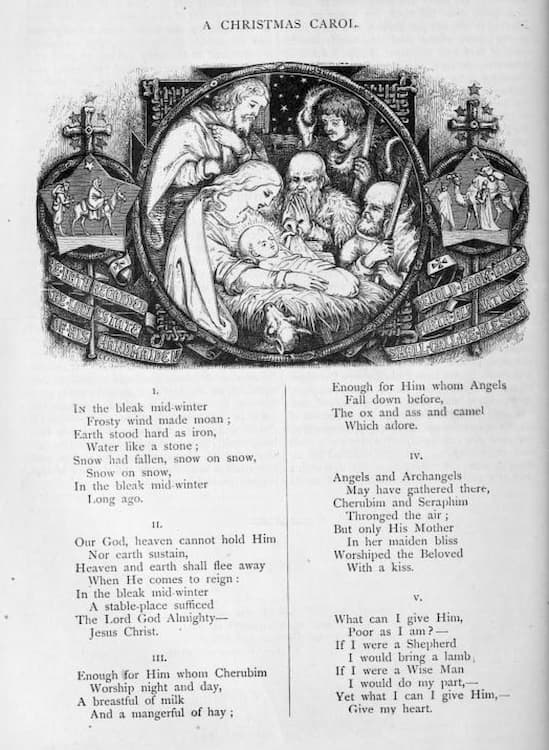

In the bleak mid-winter 1872

My second day of writing, and the frost has been covered with a heavy fall of snow overnight. Another perfect winter landscape, softer-edged, though the individual branches and twigs of trees and bushes have their own individual ice coating, and the dried umbellifers of the dormant bronze fennel are like iced stars. Christina Rossetti’s much-loved poem/carol, ‘In the Bleak Midwinter’ (1872) best sums up the scene:

In the bleak midwinter

Frosty wind made moan

Earth stood hard as iron,

Water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow,

Snow on snow.

The scene here doesn’t actually feel bleak, because of the softening edges the snow gives, and the way it beautifies. But Rossetti is after something else: this is a ‘bleak midwinter / Long ago’, the midwinter of Christ’s birth. Rossetti is of course Anglicising the event, imagining an English stable in December weather and taking no note of debates about either the date of the birth of Christ or its geography. But she also wants to call to mind the spiritual beacon that the birth is, so placing it imaginatively in the dark middle of winter makes this more striking, as does the already-existing Biblical image of the vulnerability of the baby lodged only in a manger in a stable. Perhaps there’s a further hidden reference, in the quite dark tone of the poem’s opening, to the suffering on the Cross that is to come. But what appeals to any reader of these words is the simplicity and realism of the scene she paints – a bleak mid-winter, only ‘a breastful of milk’ to sustain the child and a ‘mangerful of hay’ to soften and warm his bed, a lamb the only offering possible from the shepherd. In this context the poet’s gift of ‘my heart’ to end the poem remains both simple (it is all she can give) and full of meaning. Celebrating midwinter

Thus in the same way as Coleridge, though within an entirely different aesthetic and poetic tradition (Rossetti’s is the Victorian lyric tradition), she uses a natural scene as a jumping- off point. Until we reach the last line of the first verse – ‘long ago’ – we think we are in the present, then we move in the second verse immediately to the poem’s actual subject: ‘The Lord God Almighty – Jesus Christ’. Rossetti was a deeply religious person and poet, but her touch in the poem is as soft and light as a snowflake itself. Nothing is imposed, all is simply described, and thus it carries the reader with it, or the singer of the carol – the way in which so many of us must have encountered it.[3]

This wouldn’t be an accurate account of writers drawing on winter as an inspiration if I didn’t mention the dreariness that can accompany this season, envisaged as the original subject of this blog. Thomas Hardy can be relied upon to find gloom wherever he looks, as here in ‘The Darkling Thrush’ (1900)[4]:

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

Yep – that’s the dreary winter scene I was first thinking of. Hardy continues:

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The lyres would of course have to be broken, the Frost ‘spectre-grey’, and ‘dregs’ underscores the sense of what we used to call the fag-end of things. This isn’t Coleridge’s ‘ministry’ but rather an expression of some essential gloom of spirit, as Hardy continues the death-bound imagery: Celebrating midwinter

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

So far, so reliable from Hardy. But then the poem takes a surprising turn, as ‘a voice arose’

In full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited. Celebrating midwinter

Song thrush in winter

Significantly the poet gives us the song first, ‘voice’ and ‘evensong’ suggesting a human source; but then:

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

Notes of pessimism still abound – the thrush is ‘frail, gaunt, and small’ and ‘blast-beruffled’ – but this is only to be realistic for a bird in the middle of winter, and an aged one at that. And its very frailty makes it all the more heart-lifting that he produces ‘such ecstatic sound’. There’s no holding back on the height and power of the song and the experience; the thrush chooses to ‘fling his soul’ in ‘a full-hearted evensong’, in spite of the contrasting gloom of the scene.

Like Coleridge, Hardy is anthropomorphizing nature here, but in a way that in itself seems entirely natural. What human, hearing the thrill of birdsong, especially in the depth of winter, does not read a meaning of hope or joy into it, even if those feelings can’t be ascribed to the bird itself? And Hardy does not hang back from so ascribing them:

I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

As in his poem ‘The Oxen’ – where he imagines the oxen kneeling in their pen on Christmas Eve as of old lore, ‘hoping it might be so’ – Hardy cuts against his usual pessimism (which can be profound) and allows Hope into the poem via the thrush’s song. Even if it is a hope of which ‘I was unaware’, it takes precedence in the poem by its very utterance through the bird’s song, and through the rhapsodic words Hardy uses to describe it.

The poems I have commented on all draw on the concept of pathetic fallacy – the mistaken notion that nature is in tune with human emotion (mistaken because nature is actually indifferent to human emotion, and does not itself have or express emotions; the sense of an affective communion is imposed by humans on nature to mediate and express their own emotions). That this is a fallacy doesn’t seem to stop its being a mainstay of English poetry, probably because it comes so naturally to humans to see their feelings reflected in the natural world, or indeed to be affected emotionally by that world. It has its strongest expression in Romantic poetry of the nineteenth century: Wordsworth, Keats, Byron and of course Coleridge himself. But I’d like to end with an example from modernist prose writing of the early twentieth century. The modernist writers were highly sceptical of such notions of communion, being more likely to see and to try to express a split between human sensibility and an indifferent nature. Theirs is a world of fracture rather than unity, since as writers they sought to give accurate expression to the multiplicity of perception rather than one singular perception. For them then to imagine a unitary connection between the natural world and human emotion would be to suggest that the world is knowable and fully expressible, and that there is an unbroken continuity between human and nature. It would thus be to leave out all that is uncertain, contingent and incomplete. Celebrating midwinter

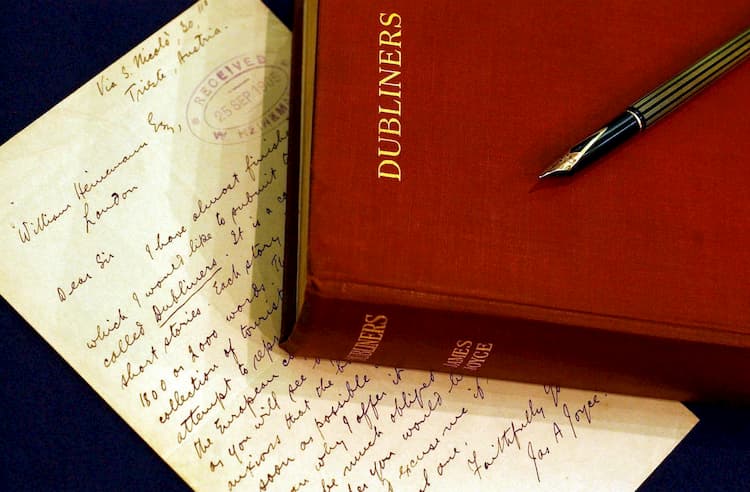

Joyce’s letter re ‘Dubliners’

However, James Joyce, in the final short story of his seminal collection Dubliners (1914), ‘The Dead’, brings off the feat of reflecting that unknowability in a fully modernist way, whilst at the same time drawing for the final image of the story and the collection on a pathetic fallacy as full-blown as that of any Romantic poet. The secret to this is that Dubliners must be read as a whole, with each individual story representing one facet of human life (and here it is traditional in that it starts with childhood and ends with old age and death). By the time we get to the final story, we have a sense of a whole array of different lives and consciousnesses, jostling with each other in a world which is at once the recognizable, realistically invoked city of Dublin, and the inner world of the individual (often completely at odds with the realist outer world). It is this fracture between outer and inner in each story that cumulatively represents across the collection the essential isolation of the individual even in a world of busy action.

In this urban setting, the seldom-invoked larger natural world is however still used at key moments as a metaphor for the inner self, usually in a moment of inner illumination or epiphany. However, unlike Coleridge’s epiphanies, melding moon, frost, infant, larger nature, and ultimate Creator in the poetic lyricism of his language, Joyce’s epiphanies are characteristically expressive of tragic isolation. Characteristic is that experienced by James Duffy at the end of ‘A Painful Case’, where, reviewing his treatment of a woman who had loved him and whom he had rejected, he concludes, ‘No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast.’ That he has himself contrived being outcast only makes it the more painful. Epiphanies in Dubliners then are more usually moments when the individual understands in a flash of illumination the nature of their own alienation – the very opposite of Romantic unity. Celebrating midwinter

Joyce’s method in this respect is firmly established when we reach the final story, ‘The Dead’. And in the narrative structure of the story itself, there is a sudden overturning of understanding in Gabriel, the chief protagonist, where he realizes that his interpretation of the evening’s events, and of his much-loved wife Gretta’s feelings, have been entirely mistaken. As she reveals that she has been thinking of a young man who loved her long, long ago, a man who had, she thought, ‘died for me’, he realizes that the evening has really been about the approach of death which comes to us all. Completely separated now as he feels from Gretta, his conception of their whole life together suddenly pulled from under him, nonetheless, ‘Generous tears filled Gabriel’s eyes’. He thinks of the poor young man so many years ago, then:

Other forms were near. His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling.

In a remarkable ending to one of the great modernist works, Joyce then turns this moment of void and dissolution into a unifying vision. True, the unification is that of death; but if only in death, we are all united, under the cold and indifferent, but in the writer’s hands temporarily comforting, blanket of snow:

Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves … It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead. Celebrating midwinter

Looking out of my window I see the actual snow still lying thickly, after a further fall; and I both see it as it is, realistically as Joyce describes it, and also understand exactly his use of it as a larger metaphor. That both can co-exist, through our sentient understanding of the natural world, and our ability to give that world further meaning through the use of language, is one of the great wonders of being human.

Other than ‘Frost at Midnight’, the works mentioned above can be found in the Wordsworth editions below:

Charlotte Brontë: Jane Eyre

Thomas Hardy: The Collected Poems

Christina Rossetti: Selected Poems

James Joyce: Dubliners

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Poems are widely available, and the full text of ‘Frost at Midnight’ can be found at www.poetryfoundation.org

Other Romantic poets published by Wordsworth include

William Wordsworth: The Collected Poems

John Keats: The Complete Poems

Lord Byron: Selected Poems

[1] The first sentence of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Though I don’t talk about this example, it typifies Brontë’s use of bad weather to alert us to the theme of confinement in the novel. She also uses it as a jumping-off point into Jane’s imagination as, no walk being available, she must travel in her mind through the medium of books.

[2] The first version of the poem was written in a bitter February, 1798, in Coleridge’s cottage in Nether Stowey, Somerset, where he had moved in 1796. The baby is Hartley, Coleridge’s firstborn.

[3] Rossetti’s poem was actually first published under the title ‘A Christmas Carol’ in Scribner’s Monthly in January 1872, and collected in book form in 1875. Its two familiar musical settings were both written in the early twentieth century, one by Gustav Holst, the other by Harold Darke.

[4] ‘The Darkling Thrush’ is a turn-of-the-millenium poem, first published on December 29th, 1900 (hence the words ‘the Century’s corpse outleant’), which gives extra significance to its embodiment of a frail hope.

Main image: Winter scene taken by Sally Minogue

Image 1 above: Coleridge painted by Pieter van Dyke in 1795 Credit: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Text of the carol In the bleak midwinter 1872 Credit: History and Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Song Thrush in the snow Credit: Juniors Bildarchiv GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: A letter dated 1905 from James Joyce to the publisher W. Heinemann offering ‘Dubliners’. Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Celebrating midwinter

Celebrating midwinter

Celebrating midwinter

Celebrating midwinter

Celebrating midwinter

Books associated with this article

Selected Poems of Christina Rossetti

Christina Rossetti

The Collected Poems of Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy