Keith Carabine on the quality of Mike Irwin’s Hardy introductions.

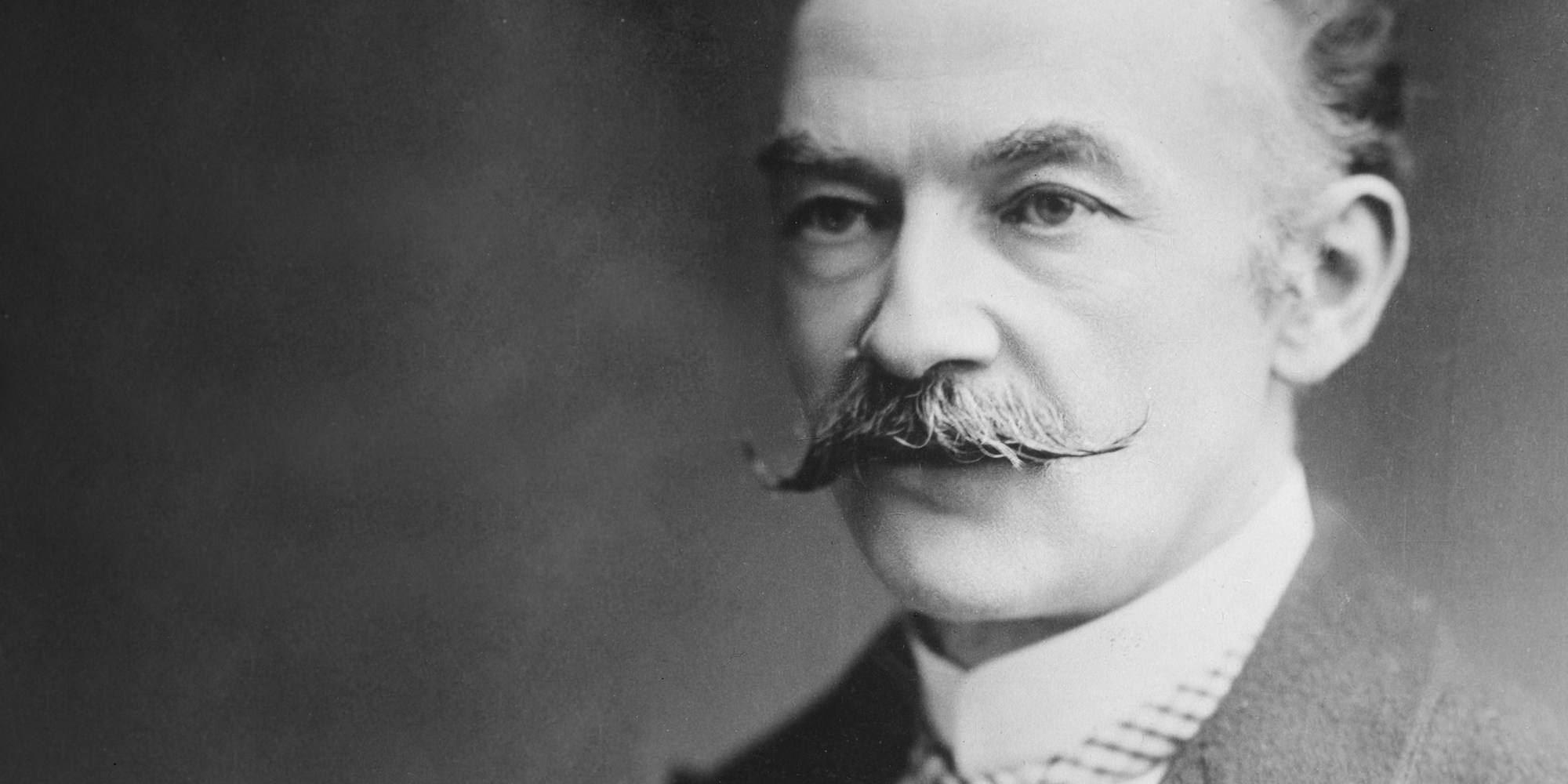

The first twelve Wordsworth Classics published in May 1992 included Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Uurbervilles, quickly followed by The Mayor of Casterbridge, and now our list contains eleven novels, two volumes of short stories and the Collected Poems. When I became General Advisor for the Classics series in 1997 I could, fortunately, draw on the expertise of my colleague and friend Michael Irwin who was teaching a hugely popular ‘Option’ on Hardy’s prose and poetry and preparing a book, Reading Hardy’s Landscapes which was published in 2000. Mike is the author of three novels: Working Orders (1969), Striker (1987) a funny, moving and beautifully crafted novel about a footballer, and recently The Skull and the Nightingale (2014), a brilliant, intriguing novel of letters set in mid-eighteenth-century England. Mike has also written librettos for a light opera, Pooter, Promised Land an opera, and he has translated fifteen opera libretti for Kent Opera.

Mike has written very fine introductions to Wessex Tales (1999), Tess (2000), The Mayor of Casterbridge (2001), Desperate Remedies (2010) and The Collected Poems (2002). The reader knows he is in good hands from the assured opening to Mike’s Introduction to Wessex Tales (his first for Wordsworth): ‘Thomas Hardy was a great novelist and a great poet. In both mediums he shows remarkable consistency, not in the sense that everything is equally good – he could be a very uneven writer – but in that all his work, from first to last, displays the same habits of vision and imagination. The mind-print is utterly distinctive.’ Mike illustrates these ‘habits’ at work in Hardy’s presentation of time ‘as both a developing and a destructive process, changing lives and landscapes’, and even objects such as ‘the family mug’ in ‘the Three Strangers’- ‘a huge vessel of brown ware, having its upper edge worn away like a threshold by the rub of whole generations of thirsty lips that had gone the way of all flesh.’ Mike’s intelligent, lucid, and deeply felt appreciation of Hardy’s distinctive ‘habits’ and achievement is evident in the final reflections of his Introduction to Wessex Tales:

In these stories, as in Hardy’s fiction in general, we are invited to see human life from great distances, to reflect with melancholy upon its frailty, its brevity and its sorrows. As a tale closes, its characters recede, recede into the remote specks he so often describes. But within the stories, in passionate counterpoint, is a recurring awareness of how brilliantly, how unreservedly, we can be enthralled by life from moment to moment, relishing hope, love, a dance, an adventure, a spring day, a moonlit night. The brevity of our existence is so sad precisely because its promises can be so bewitching. What is often described as Hardy’s pessimism is the shadow cast by the intense light of his imaginative and emotional vitality.

If any reader has read anything on Hardy’s fiction finer than these beautiful reflections, please let me know and I will include your suggestion in a future ‘Note.’

Keith Carabine

Books associated with this article

Tess of the d’Urbervilles

Thomas Hardy

The Mayor of Casterbridge

Thomas Hardy

Wessex Tales

Thomas Hardy