Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

‘The great drama of his life was the struggle for a better state of things in Russia.’ (Henry James on Ivan Turgenev)

The publication of Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons (1862) caused an unprecedented sensation in Russia. Sally Minogue has a look at its contemporary context, and at the novel as we might read it today.

I have been banging on about the large scale of the nineteenth-century Russian novel, its interest in big ideas, and its attempt to span the massive breadth of Russian history, landscape and cultural identity. All true. But Ivan Turgenev sketched his first plan, characters and central ideas for Fathers and Sons … on the Isle of Wight. In a boarding-house in Ventnor, in the unseasonably inclement August of 1860, the novel that has been described as raising ‘a tempest in Russia by its appearance’ was born.[1] Difficult to imagine a place more at odds with the writer’s subject matter or his grand ambition. But in fact Turgenev spent much of his life outside Russia, largely in Europe. After going to university in Moscow and St Petersburg, in 1838 (aged 20) he went to study philosophy at the University of Berlin, at that time in the kingdom of Prussia, where he met the veteran anarchist and revolutionary thinker Mikhail Bakunin. He spent long periods abroad, mainly in France. His visit to the Isle of Wight was part of a tour that also took in Germany, Italy and Austria. Turgenev’s attraction to Europe was in part because Russia under the rule of Tsar Nicholas I was a difficult climate for many writers, and in part because of his passion for the opera singer Pauline Viardot, whom he met in 1843. Viardot was married, her personal and professional life was rooted in Europe, and Turgenev eventually adopted a sort of intermittent ménage à trois with her and her husband.

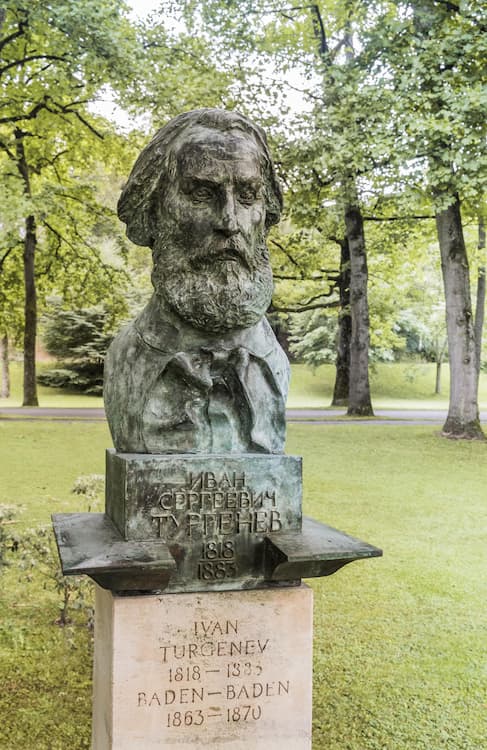

Bust of Turgenev, Baden-Baden, Germany

Turgenev admired Western values, and belonged to that group of thinkers who believed that Russia would benefit from ‘Westernisation’ (partly in reaction to the authoritarian nationalism of Tsar Nicholas). But Russia remained Turgenev’s abiding passion, the centre of his identity, and the subject of his writings, and his espousal of Westernisation sprang from a commitment to seeing Russia flourish. In particular, he and his fellow-thinkers hated serfdom, which right up to the early 1860s when Turgenev was writing his novel, remained the dominant structure of Russian rural society, with the peasants being effectively enslaved to their aristocratic owners. This became a major issue in mid-nineteenth-century Russia, and divided the nation. Turgenev deliberately sets Fathers and Sons not contemporaneously with his writing it, but a couple of years before, in 1859, just before the enactment of the legislation which emancipated the serfs (Edict of Emancipation, 1861). But the divide he explores between fathers and sons – between the entitled generation and their protesting sons – is not in fact that between Turgenev’s generation of Westernisers and their land-owning fathers. Rather, in his ‘hero’ Bazarov, he depicts the new revolutionary, who has no truck with halfway measures, even those of Westernisation. Nihilism is the philosophy Bazarov embodies, and in spite of the emptiness suggested by the name (belief in nothing), in fact this second wave of radical thinkers embodies a revolutionary principle, that of starting from first causes, rather in the scientific manner, expressed in Bazarov by his constant interest in dissection. Nothing is assumed, nothing fore-ordained. Authority in all its forms must be flouted. In such a philosophy, not only would serfdom be overthrown, but so would the aristocracy which depended on it.

Bazarov is therefore a forerunner of much later Russian revolutionaries, and his radical nature may in and of itself have disturbed one part of Turgenev’s readership. But at the same time, those who espoused Bazarov’s ideas – the new generation of radicals and activists coming up after Turgenev – felt that the novel gave an unfair picture of those ideas. In particular, they were unhappy that Bazarov was killed off at the end of the novel, the fictional fate in so many nineteenth-century novels of those who didn’t fit into their society’s norms. But perhaps the real problem for those who espoused Bazarov’s cause was the nature of the character himself. He is not easy to like. Arriving as an unannounced guest at his fellow student Arkady’s country estate, he appears arrogant, constantly yawning as if bored with whatever question is put to him. He is disrespectful to, and in private with Arkady contemptuous of, Arkady’s uncle Paul (a Westerniser). When they discuss their different ideologies, Bazarov makes plain how fully and finally mistaken are Paul’s ideals and values, to the point that he throws to the wind all rules of hospitality. To his own parents he is barely civil, though he is clearly aware of how they dote on him. And on his second visit to Arkady’s household, he flirts with the young woman Theodosia/Thenichka (the mother of a baby by Arkady’s father, and of recognized status in the household), and seizes a kiss from her. Whether he does this carelessly, or even worse, deliberately, he does it when he has been admitted to her intimacy through his medical care for her child. He rides roughshod over undeserved authority wherever he meets it, but in Thenichka’s case he uses the authority of his own class and gender to misuse one weaker in all ways than himself. Moreover, he rouses Thenichka’s own natural feelings for a good-looking young man and makes her feel complicit in the kiss.

And yet Bazarov has more worth than all this errancy suggests. Firstly, his attitudes and behaviour are derived from a genuine belief in complete freedom of thought and value, unfettered by any preconception. He has the difficult role in the novel of both representing the Nihilism Turgenev wanted to explore, and of being a complex human being who feels things that he by his own lights knows he should condemn. We see the real torture of his love for Madame Odintsov, which persists even when she rejects him – a state he would be contemptuous of in others (in fact it mirrors Paul’s clinging on to his hopeless pursuit of Princess R., one of the weaknesses in him that Bazarov mercilessly attacks). Perhaps the most sympathy we feel for him is when he looks enviously at the ‘normal’ lives of others and wishes he could occupy his life unthinkingly as they do. In a significant conversation with Arkady as they lie indugently together under a hay-rick on the visit to Bazarov’s family home, he considers his own existential isolation in comparison with his parents’ happiness in their everyday existence:

‘…the portion of time allotted to me here on earth is insignificant indeed compared with the eternity which I have never known, and shall never enter! Yet in the same atom, in this same mathematical point which I call my body, the blood circulates, and the brain operates at will. A fine discrepancy for you – a fine futility! …

What I mean is that my parents know not a single tedious moment, nor are in the least distressed with the thought of their insignificance – … whereas I – well, I feel nothing but weariness and rancour in my breast.’ (p. 124)

Zhuravlev Firs Sergeevich – Peasants’ Gathering

This is the Socratic dilemma, but it also echoes Hamlet’s cry of angst, ‘How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable/ Seem to me all the uses of this world’. Bazarov is caught in a terrible bind: his ideology dictates that he must condemn the unquestioning immersion in the petty everyday world where one just is, yet at the same time he longs for that immersion, and the means that would lead to it. A further irony here, which Turgenev does not spare either us or Bazarov, is that his parents are very far from never knowing ‘a single tedious moment’, since they are half-mad with grief at their son’s apparent indifference to them. It doesn’t help anybody that his very indifference is a sort of willed response arising from his Nihilism. So Bazarov is also an early example of the existential anti-hero, more familiar in twentieth-century modernism, isolated from his kind by an over-awareness of the shallowness of most human existence; yet at the same time he is committed to a set of ideas which he feels it absolutely necessary to follow. There’s very little comfort for him between these two positions.

The counterpoint to Bazarov is his friend Arkady, who tries to follow the same principles as Bazarov but is all too fond of those ‘shallow’ aspects of human life to be able to deny himself them. Turgenev’s writing of this relationship is particularly clever, as he explores both its genuine warmth and the inherent difference between the two men which must eventually lead to their parting. The quotation above comes from a long, significant passage in the novel, where the two men begin by relaxing together in companionship:

Later, when the noontide sun was glowing from behind a thin canopy of dense, pale vapour, and all was still save that the chirping of a few birds in the trees lulled the hearer to a curious, drowsy lethargy, and the incessant call of a young hawk on a topmost bough made the air ring with its strident note, Arkady and Bazarov made for themselves pillows of sweet, dry, fragrant, crackling hay, and stretched themselves in the shadow of a rick. (p. 123)

This beautiful pastoral writing is characteristic of Turgenev and is one of the pleasures of the novel. Yet the scene ends in a physical quarrel in which Arkady glimpses his friend’s true self: ‘Bazarov’s face, with its expression of malice and the non-jesting menace which lurked in the twisted smile and the flashing eyes, gave him a shock’. (p. 128) As Bazarov’s father enters, perceiving only a boyish tussle, Bazarov quietly apologises and Arkady clasps his hand in forgiveness. It is a moment of true feeling; but the scene prefigures their necessary separation. Arkady is gradually drawn to the youthful Katya, and to the quotidian pleasures of marriage – like those drawn by Bazarov picturing his parents’ marriage. Bazarov has already revealed his love to Katya’s very much more adult sister, Madame Anna Sergievna Odintsov, to have it at once both apparently reciprocated and then rejected. Bazarov naturally sees this love as a weakness in himself, yet he is unable to let it go. Here again we are attracted to his humanity and the tensions within himself that he has to contend with.

Painting by Boris Kustodiev depicting Russian serfs listening to the proclamation of the Emancipation Manifesto in 1861

Bazarov carries the central ideas of the novel, and I’ll return to these as they are embodied in his fictional fate. But the other part of the balance of ideas in the novel is provided by the ‘fathers’ to whom Bazarov and Arkady are the ‘sons’. The Russian title of Turgenev’s novel actually translates as ‘Fathers and Children’ but given that the only paternal relationships depicted in the novel are with sons, reflecting the patriarchal structure of nineteenth-century Russia, ‘Fathers and Sons’ is the title that translators have fixed on. But its real intention is to refer to a generational divide of a larger and perhaps less gender-specific kind, between one set of approaches to the world and another, which is interestingly specified by Nikolai Petrovich, talking to brother Paul, by his recalling a quarrel not with their father but with their mother:

‘During the contest she raised a great outcry, and refused to listen to a single word I said; until at length I told her that for her to understand me was impossible, seeing that she and I came from different generations. … And now our turn is come; now is it for us to be told by our heirs that we come of a different generation from theirs, and must kindly swallow the pill.’ (p. 54)

Turgenev’s gift as a novelist is that he is able to show the human cost on both sides, whilst also depicting the larger generational, indeed historic, struggle. It is clear from his writings outside this novel, and from his own political leanings, that he sees the generation of landowners such as Nikolai Petrovich as outmoded and outdated, principally because of the way they have hung on to and depended upon serfdom. Yet within the novel itself it is difficult not to feel some sympathy with them. The ‘estates’ that Turgenev depicts are not thriving places. On Nikolai Petrovitch’s land there is a sense of general decay. (See p. 12, pp. 136-138) And Bazarov’s father Vasili Ivanitch, whose lands are even poorer, appears to be on a par with his peasantry, ‘clad in a smock-frock and belted with a handkerchief’, ‘preparing a bed of late turnips’, when Arkady encounters him on the first morning of their stay. (p. 120) This sense of decay, disorder and social breakdown is in part intended to express the inherent corruption of a system of landowning and agriculture that depends on serfdom, yet neither Vasili Ivanitch nor Nikolai Petrovich seem like bad men.

Set of 19th-century flintlock duelling pistols.

The central vehicle in the novel for the opposition of ideas between the old liberal Westernisers and the young radical Nihilists is a clash, not between father and son, but between Arkady’s uncle, Paul Petrovich, and Bazarov. Where the tensions between actual fathers and sons are tempered by familial affection, there is no love lost between Paul and Bazarov. This enables Turgenev to explore the hostility each feels for the other in terms of their ideas, unsoftened by any other claims of feeling. That hostility comes to a head over the stolen kiss from Thenichka, which Paul has observed, but the resulting duel is really that between two ideologies, and two claims on the future of Russia. However, Turgenev punctures the potential seriousness of this event with a series of ironies. To today’s reader, a duel with pistols over a perceived moral offence by one party to the other may seem a ridiculously antiquated idea. However, in nineteenth-century Russia duels were still current – the great writer Alexander Pushkin, beloved in the novel by the older generation, is said to have fought many duels before finally dying in one in 1837. Indeed in the course of an often turbulent relationship between the two great writers, Leo Tolstoy challenged Turgenev to a duel in 1861 around the time that Fathers and Sons was completed. Through a series of miscommunications, the duel never took place but Tolstoy and Turgenev did not meet for the next 17 years, finally being reconciled in 1878 when Tolstoy wrote him a letter begging forgiveness. There are certainly elements of both deep seriousness and absurdity in the quarrelsome relationship between the two writers. The duel Turgenev depicts between Paul and Bazarov (Chapter 24, pp. 147-157) is skewed towards absurdity. When Paul is laying down the conditions of the duel, including each writing a letter taking full responsibility should the other one die, Bazarov objects: ‘“I think you are straying into the pages of a French novel.”’ There are no seconds, so the valet Peter is dragged in as an extremely reluctant witness. Bazarov has no pistols and has to borrow a pair from Paul, who assures him that they have not been fired for five years, as though this were some sort of reassurance. As Bazarov comments: ‘“Splendid indeed! Yet also unutterably stupid!”’ For him, with his alertness to the absurdity of life, this is existential comedy of a high order, and so the event proves. Paul is late because he didn’t want to wake up his own manservant at this early hour. The witness Peter is petrified, doesn’t want to watch, and takes cover behind a distant tree. As the two combatants face each other, Bazarov reflects with surprise, ‘“The fellow is aiming straight at my nose … This is not a wholly pleasing sensation.”’ In fact Paul’s shot whistles past Bazarov’s head, Bazarov fires without taking aim, and Paul sustains a flesh wound in his leg. Bazarov turns from duellist to doctor, and honours are regarded as even. The possibility of a fatal outcome is only lightly touched on.

In terms of the conflict between the two big opposing ideologies of the novel, this almost comic treatment of the clash between the two main protagonists seems to deflect any over-seriousness. Yet it leads to Bazarov’s necessary departure from the Kirsanov household, and a last visit to Madame Odintsov (during which time she is now regularly referred to by Turgenev as Anna Sergievna) which only confirms her rejection of him – and her understanding that he still loves her. At the same time he parts forever from Arkady, with an acute but hurtful summary of his unfitness to be a true Nihilist. Thence he returns home to assist his father in medical duties, where the final act in his tragedy comes about through negligence of a sort that might be seen as wilfully self-destructive. For though as a doctor he well knows the dangers of typhoid, his intellectual curiosity is too much for him to resist the opportunity of dissecting the body of a peasant who has just died of it. The dénouement is revealed only in passing as he asks his father for treatment of a cut on his hand, made during the dissection. Both men know the grave danger, and when Bazarov falls ill and is sure that he is dying, he sends for Madame Odintsov. While there is no deathbed reconciliation of love declared – indeed she knows that she does not love him – she is nonetheless there beside him as a comfort.

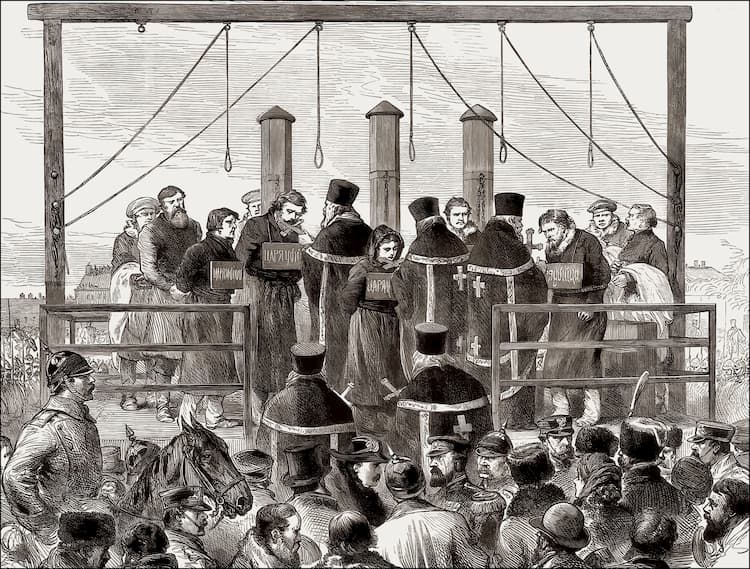

The Nihilists executed at St. Petersburg, Russia, 1881

Yet such a death, and such an ending to the novel, here takes away from rather than adds to Bazarov’s power. He is reduced in the fiction to a stereotypical tragic ending, the woman he has loved bestowing a farewell kiss on his forehead, and his being given the Last Rites of a religion he does not believe in because he has softened towards his parents. It is left to his father to make the final enraged protest to the heavens. Thus the coherence of Bazarov’s representation of radical Nihilism in the novel is undermined by what feels almost a cheap stage trick. Whether we see this as a failure of novelistic courage, or an admirable realism on Turgenev’s part about the likely outcome for a revolutionary thinker who has no battlefield to fight on, it was central to the outcry from those of his contemporary readers who espoused Bazarov’s beliefs. For them, the novelist presented too sympathetic a picture of the old régime. No doubt they were also responding to the fact that Turgenev himself came from and benefited from that very landed class that he attacks. For his part, Turgenev, infuriated by what he felt were misunderstandings of the novel, asserted both that it was directed firmly against the landed nobility, and that he did not know whether Bazarov should be praised or blamed: ‘I don’t know that myself, since I don’t know whether I love him or hate him!’ (see Introduction, p. ix) The year after the novel’s publication, Turgenev left Russia to make a semi-permanent abode in Europe.

The abiding image of Fathers and Sons for me is not of Bazarov but that of his aging parents. When he cuts short abruptly his first visit to them, thoughtless of the many preparations they have made and expectations they have had, they are left devastated. No longer must they keep up a pretence of resilience to their son:

When the old couple found themselves alone in a house which seemed suddenly to have grown as dishevelled and as decrepit as they – then, ah, then did Vasili Ivanitch desist from his brief show of waving his handkerchief in the verandah, and sink into a chair, and drop his head upon his breast.

‘He has gone forever, he has gone forever,’ he muttered. ‘He has gone because he found the life here tedious, and once more I am as lonely as sand in the desert!’

(p. 134. The longer passage is worthy of a close look, as it is so movingly written)

The feeling of being left behind, abandoned even, either actually or in terms of ideas, is very strong in the novel, and perhaps Turgenev’s inherent sympathy with that feeling is stronger than his intellectual sympathy with Bazarov’s revolutionary ideas. When Bazarov dies, the old folk subside once again, Arina with her arms around her husband Vasili’s neck:

and the two sank forward upon the floor. Said Anisushka later, when recounting the story in the servants’ quarters: ‘There they knelt together – side by side, their heads drooping like two sheep at midday.’ (p. 195)

The same image of despairing loss is reiterated with the depiction of the grieving pair at Bazarov’s tomb on the final page of the novel:

Supporting one another with a step which grows ever heavier, they approach the railing, sink upon their knees, and weep long, bitter tears as they gaze at the dumb headstone where their son lies sleeping. (p. 200)

In that dead son’s eyes this would all be errant folly, the product of a bourgeois commitment to the values of marriage and family which he roundly attacks in his life – the ‘nest’, as he contemptuously describes it, which Arkady has chosen to share with Katya, those familial bonds which lead Arkady to defend Paul, and which Bazarov openly despises. But it is the final powerful image of the novel, and one which cannot fail to move. For myself, it reminds me strongly of Käthe Kollwitz’s bleak memorial to her son Peter who fell in the First World War, The Grieving Parents.[2] Kollwitz was born in 1867 in Prussia – the next generation. Her striking sculpture expresses both personal grief and a bleak existential modernism, and who knows but that the first inkling of it in her imagination might have come from Fathers and Sons?

[1] American scholar Eugene Schuyler, first translator of Fathers and Sons into English in 1867.

[2] Completed and installed in the Belgian Cemetery of Roggevelde 1932, and then moved to the Vladslo German War Cemetery when Peter’s grave was moved there.

Main image: The Grieving Parents of Berlin by Käthe Kollwitz Credit: Arterra Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Bust of Turgenev, Baden-Baden, Germany. Credit: Zoonar GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Zhuravlev Firs Sergeevich – Peasants’ Gathering – Russian School – 19th Century Credit: Artepics / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: A 1907 painting by Boris Kustodiev depicting Russian serfs listening to the proclamation of the Emancipation Manifesto in 1861 Credit: CBW / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 4 above: Set of 19th-century flintlock duelling pistols, State Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia. Credit: Ivan Vdovin / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: The Nihilists executed at St. Petersburg, Russia, 1881 Credit: history_docu_photo / Alamy Stock Photo

Our edition of Fathers and Sons can be found here

A good summary of his works can be found here

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Turgenev’s ‘Fathers and Sons’

Books associated with this article