Yorkshire’s Literary Influence

Does it make sense to think of writing as belonging to a particular place? Sally Minogue reflects on the influence Yorkshire has had on our national literature.

A couple of weeks ago I was staying in Yorkshire, my native county, not, as usual, in the homes of my sister or niece, but in a little rented cottage. I was thus both at home and not at home; in the familiar landscape and culture of my childhood, but slightly displaced from it. While I was there various members of the family visited and stayed over, we had walks together, ate together, and for them too it was a holiday both at home and from home. This, and walking in close acquaintance with the countryside of my childhood, led me to reflect on the way our native places affect our understanding of the world. In particular, it led me to think about writers and writing in relation to those places.

Certain parts of Britain are closely associated with the writers who came from them. We think of Dorset and Thomas Hardy; D. H. Lawrence and Nottingham; Robbie Burns and Dumfries; Dylan Thomas and Swansea; W. B. Yeats and Sligo. But what of the many other writers not so closely associated? Do we make the above-mentioned connections because those writers wrote particularly about the countryside they grew up in, or is it rather that they have come to be associated with them almost in a touristy way? I remember driving in Ireland once and seeing a sign saying ‘You are now entering Yeats country’. In my mind, Yeats was an arch-modernist, and while he might have been buried in Sligo, I’m sure he’d have been appalled for his writing to be characterised by that. James Joyce flew by the nets of nationality, lived much of his life in Europe, and is buried in Zurich; he did his damnedest to be a citizen and a writer of the world. But when we think of him, we think first of Dublin.

Haworth Church and Parsonage

Yorkshire is forever associated with the writers Emily, Charlotte and Anne Brontë, and I have written elsewhere about the significance of Haworth and its bleak moors to their work. [See here and here] Yet Charlotte’s (in my view) best novel, Villette (1853), is set in Belgium, and derives its particular power from the foreignness of its location and the effect that has on its central character Lucy Snowe. It is often forgotten that Emily travelled to Brussels with Charlotte, their joint intention being to equip themselves with the skills to set up a school back at home. Emily spent from February to November of 1842 in the Pensionnât Héger. Not for her the inner emotional turmoils of Charlotte over M. Héger; rather she concentrated on her language skills and intellectual development. M. Héger had a high opinion of her: ‘She should have been a man – a great navigator. Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old; and her strong imperious will would never have been daunted by opposition or difficulty.’ When she and Charlotte returned home on the death of their brother Branwell, Emily stayed at home, while Charlotte went back to Brussels. But nonetheless she had experienced time away from Haworth, from Yorkshire, from England. She experienced a bustling cosmopolitan city, a Catholic culture, an urban environment. In 1847 she published Wuthering Heights. We see clearly the influence of her native landscape on her work, but who is to say that time away from it did not also influence her?

Wuthering Heights is endemically of the Yorkshire moors, and draws its power and atmosphere from the specifics of its natural description. But when Catherine says, ‘My love for Linton is like the foliage in the woods: time will change it, I’m well aware, as winter changes the trees. My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary. Nelly, I am Heathcliff!’, while she is drawing on those natural features as a metaphor, what she is saying is unlocalised and indeed grandiose. Anyone could identify with it, in any language, from any place. It is to do Emily a disservice to see her as an isolated, untravelled being, locked forever into the specific territory of the moors near Keighley. As much as Charlotte, she travelled in the mind.

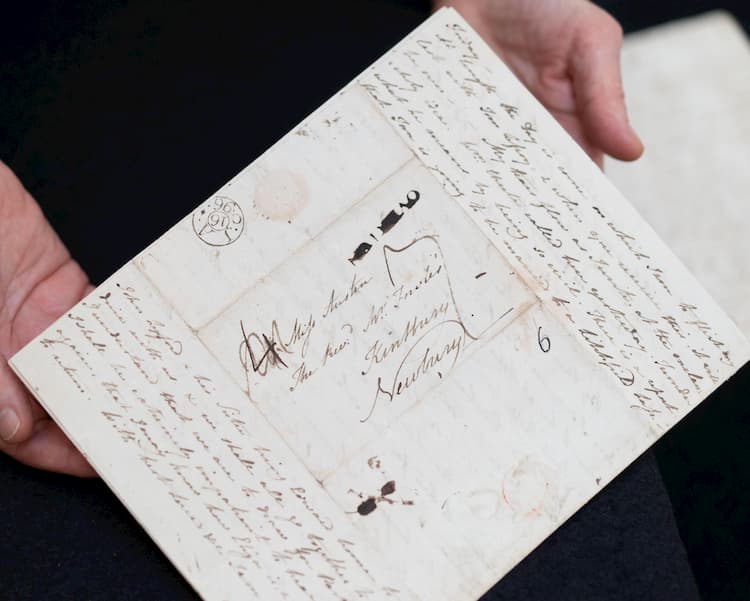

Brontë Sisters MSS

The country around Haworth is singular, and not necessarily characteristic of Yorkshire. It’s near the Lancashire border, and it’s also an industrial landscape, since there were many mills in its environs. So it’s an interesting mixture of rather bleak moorland and the marks of the industrial revolution – not necessarily the romantic notion of a Brontë landscape. I’ve visited it at many times during my life, and I feel a deep imaginative attachment to it since the Brontës were part of both my literary and my personal ‘growing-up’. They seemed to belong to us, as part of Yorkshire, and that never quite left my understanding of them as writers. But whenever I revisit I am reminded of what feels like an inherent poverty in Haworth – perhaps rooted in that damning report on the horrors of its sanitary shortcomings, with what was essentially sewage flowing downhill into its water supplies. So I feel deeply connected to that place through its centrality to such key writers in our literary history (and to me personally because in them the local and the larger world married); but I’ll always be aware of a sort of meanness in the place.

My recent sojourn was in a very different bit of Yorkshire, which is after all a very big and various county. The old Ridings, East, West and North (I was born in the West Riding), were thirds of the county, hence there could be no South Riding – which Winifred Holtby made a play of in her novel South Riding (1936). That’s all gone now, with the new bureaucratic divisions. What was my native part of the county is now North Yorkshire, and I was staying in the small but ancient village of Studley Roger, a mile from the cathedral city of Ripon and adjacent to Studley Royal Deer Park. You can’t get much further from Haworth than that. The Park contains within its grounds Fountains Abbey, a living reminder of the effects of Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries. The Abbey – now a splendid and atmospheric ruin – along with its monastic estate was sold by the Crown (c. 1539) to Sir Richard Gresham under the express responsibility that it should be rendered incapable of future religious use. As was usual in such cases, the ravaged building materials were put to good local use. The story of the whole estate echoes the history of England. The Mallory family who owned Studley Royal from 1452, were in the Civil War loyal to the Crown, and John Mallory helped to defend the nearby Skipton Castle against Parliamentary forces, eventually surrendering it in 1645. Part of the Studley estate was forfeited to Parliament in lieu.

Studley Royal Deer Park

So Studley Royal Deer Park, while close in locale, is, with its aristocratic connections and reflections of the passing of power between monarch and State, very far from my own Yorkshire childhood. It is parkland – of a very splendid kind, but still parkland, whereas I grew up in an agricultural landscape. My Dad was a labourer on several farms, and the landscape I was familiar with was a rather scrubby one, but one on which I think fondly, and which for me is characteristically Yorkshire. Wind-driven hawthorn hedges, rough lanes, roadside brambles to provide good pickings in Autumn but viciously thorned; small, relatively flat, strikingly green, or ruggedly brown ploughed fields – a farmed countryside but one that did not give in easily to that. Beasts here and there, but also crops, a mixed farming that only just hangs on now, and the whole punctuated by rushing streams and still the sense of a landscape that hasn’t quite been tamed. I listened recently to an old recording of Ted Hughes (on BBC Radio Four Extra) talking about his West Riding childhood in the Calder Valley, and that came nearest imaginatively to what it remains in my own head and heart.

Shandy Hall, Coxwold.

Yorkshire has also inspired outsiders, incomers. Laurence Sterne and Bram Stoker were both born in Ireland. But both took Yorkshire as a point of fictional departure. Sterne had a country living as a clergyman in Sutton in Yorkshire and he wrote his iconoclastic novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759/60) during his time there. Another of the points in my childhood literary lexicon was Shandy Hall at Coxwold where he lived from 1760 to 1768; these local connections were flaming beacons to me. Tristram Shandy escapes all bounds even of the novel form, and certainly any of place or nation, so it can’t in any way be said to have derived from Yorkshire even though it was written there. Bram Stoker was a different kettle of fish. In Dracula (1897), he moves seamlessly from the terrifying wilds and dreadful castle walls of Transylvania to the apparent ordinariness of Whitby, but the vampiric Count Dracula injects his fears into both. I’ve always thought Whitby was a most clever choice on Stoker’s part. It is in Mina Murray’s first journal entry ‘a lovely place. The little river, the Esk, runs through a deep valley, which broadens out as it comes near the harbour … The houses of the old town … are all red-roofed … Right over the town is the ruin of Whitby Abbey … It is a most beautiful ruin, of immense size, and full of beautiful and romantic bits.’ The whole description of Whitby could stand still today, so exact is it. Yet into this idyll drives the ship Demeter on the crest of a terrible storm, and lashed to its helm ‘a corpse, with drooping head, which swung horribly to and fro at each motion of the ship’. Thus Whitby and Transylvania are brought together, just as later the ordinariness of Mina’s and Lucy’s lodgings are penetrated by Dracula, and the romantic ruin of the Abbey is turned into a truly Gothic site by his depredations on Lucy Westenra.

Whitby Abbey

Stoker visited Whitby in 1890 as part of his research for Dracula, and what is striking in the Whitby chapters is the very close and accurate detail about the topography of the town and the Abbey. This is a marked quality of the novel; Stoker makes the extraordinary and the fearful even more so by laying it alongside the details of ordinary, bourgeois existence. The Abbey ruins are shown as part of the quotidian make-up of the town and at the same time transformed into a site of horror. The fact that Whitby is a port allows the transgressive entry of the exotic and supernatural into the ordinary, and Lucy is its victim.

I know Whitby well, and I still get some sort of thrill from recognizing the same place I have walked around in the pages of a remarkable work of fiction. We do connect those fictions with the places they come from, whether they are actual, or imaginatively realized. In the case of the Brontës’ fiction, for me they are both. But of course many readers will never have seen these places except through the writers’ pages. And perhaps theirs is a purer understanding. And it can work the other way too. Walking early one morning in the deer park, and seeing startlingly the large herd of deer in the near distance, amongst them some white deer, I thought of Thomas Wyatt’s ‘They flee from me that sometime did me seek’ (? 1535, thought by some to be about his rumoured affair with, and then rejection by, Anne Boleyn) with its play on ‘hart’ and ‘heart’, and the idea of the wild creature momentarily tamed:

I have seen them gentle, tame and meek

That now are wild and do not remember

That sometime they put themselves in danger

To take bread at my hand

For a moment, and through both the power of poetry, and of the landscape, history closed up and I was back in Wyatt’s time. The local became all-powerful, but only because of those powers of association that poetry can trigger. We’re lucky if we can attach something more, something deeper and extra, through our own individual knowledges of place and of the writing rooted there. But in the end writing goes beyond that. Wyatt was never in the Studley Royal Deer Park. But the poem was.

All the novels by the three Brontë sisters are published by Wordsworth.

Bram Stoker, Dracula, Wordsworth Editions

Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy, Wordsworth Editions

Ted Hughes, ‘The Rock’, essay broadcast originally in 1963 on the Third Programme, currently available on BBC Radio 4 Extra.

Main image: Top Withins or Top Withens, supposed setting for Wuthering Heights Credit: grough.co.uk / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: Haworth church and parsonage. Credit: Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: One of a series of manuscripts in the hands of sisters Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brontë. Credit: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 3 above: Studley Royal Deer Park. Image courtesy of Sally Minogue

Image 4 above: Shandy Hall, Coxwold. Credit: Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 5 above: Moon over Whitby Abbey. Credit: nagelestock.com / Alamy Stock Photo

See this link for details of the The Brontë Parsonage Museum

Our various editions of Wuthering Heights can be found here

Books associated with this article

Wuthering Heights (Heritage Collection)

Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights (Luxe Edition)

Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights (Collector’s Edition)

Emily Brontë

Wuthering Heights

Emily Brontë