Writings dark as a raven’s wing

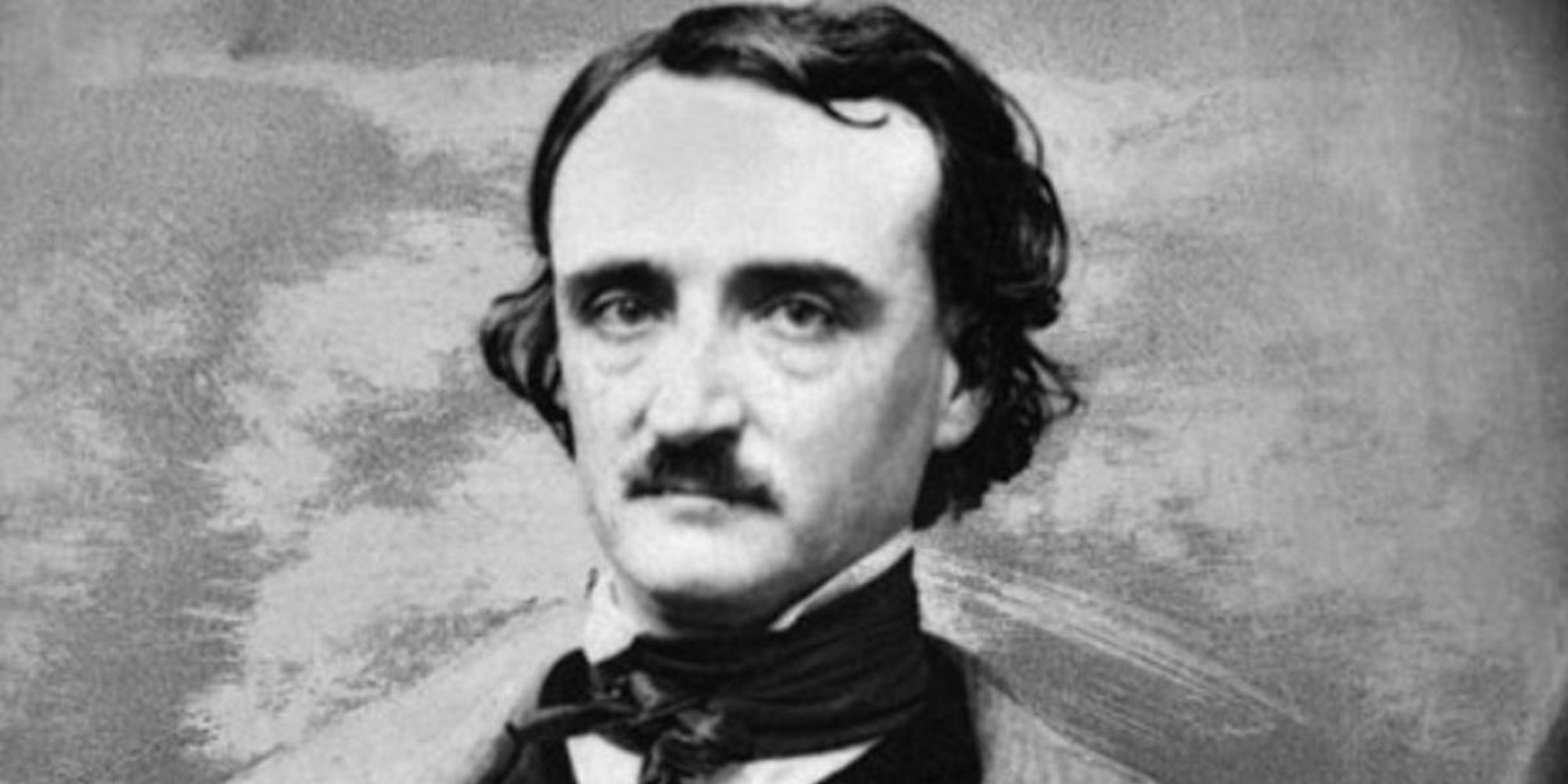

Edgar Allan Poe David Stuart Davies on the master of terror and pioneer of detective fiction.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849) was a strange man who led a strange and tumultuous life. This strangeness found its way into his fiction and although his skills as a writer were never fully recognised in his lifetime, he is now highly regarded not only for his brilliance in creating unnerving macabre supernatural tales but he is also acknowledged as the father of detective fiction.

But see, amid the mimic rout

A crawling shape intrude!

A blood-red thing that writhes from out

The scenic solitude!

It writhes!- it writhes!- with mortal pangs

The mimes become its food,

And seraphs sob at vermin fangs

In human gore imbued.

From The Conqueror Worm

Poe’s life was a tragic one. Born in Boston, the second child of two actors, his father abandoned the family within months of his birth and his mother died the following year. Thus orphaned, the child was taken in by John and Frances Allan of Richmond, Virginia. The relationship between Poe and John Allan was tempestuous and they clashed repeatedly over Poe’s debts, including those incurred by gambling. He failed to complete his university education and enlisted in the army but was dismissed for dereliction of duty. Later he watched his child bride die of tuberculosis. Though it seemed at times that the fates were against him, it is also true to say that Poe was his own worst enemy. He often behaved irrationally and was given to bouts of depression, excessive drinking and attempts at suicide.

Poe died in October 1849 in mysterious circumstances, worthy of one of his own bizarre tales. He was found on the streets of Baltimore delirious, ‘in great distress, and… in need of immediate assistance’, according to the man who found him. Poe was never coherent long enough to explain how he came to be in his dire condition, and, curiously, he was wearing clothes that were not his own.

Edgar Allan Poe’s publishing career began, albeit humbly, with an anonymous collection of poems, Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827) credited only to ‘a Bostonian’. It emerged virtually unnoticed by the reading public. Poe earned most of his income by editing literary journals and periodicals, becoming known for his own style of harsh literary criticism. His caustic reviews earned him the epithet ‘Tomahawk Man’.

It wasn’t until the publication of his poem ‘The Raven’ (1845) that he received recognition and praise for his creative output. It was in the last ten years of his short life that he created the brilliant core of his supernatural writings with such tales as ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ (1839), ‘The Masque of Red Death’ (1842), ‘The Pit and the Pendulum’ (1843), and ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ (1846). There is a strange unworldly nightmare quality about these stories and poems. The narrators have a heightened sense of the unreal and seduce the reader into sharing their visions and versions of the events as though seen through a distorting mirror darkly. The theme of retribution – often from beyond the grave – runs through much of his work, revealing to a large extent the nature of the author’s own tortured mind. Poe’s stories and poems are not only masterpieces of Gothic horror but also masterpieces of dramatic irony and structural symbolism.

After Poe’s death, his reputation was secured not in his homeland of America but in France where a collection of his works, translated by Baudelaire, was an immense critical success. Word slowly filtered back to the English-speaking countries and in time Poe’s importance was eventually realised. The now standard volume of his stories, under the title Tales of Mystery and Imagination, was first published in 1903 and has never been out of print since. These narratives have been incalculably influential in the horror and supernatural fiction genre: the startling images and themes provide a master class in achieving frissons of chilling and spine-tingling terror.

Similarly, Poe’s tales featuring C. Auguste Dupin, his brilliant but eccentric sleuth, laid the groundwork for future detectives in literature. Dupin performs feats of ‘ratiocination’ – a word coined by the author himself – in order to solve crimes. The detective, who resides in Paris and shuns daylight, lives behind closed shutters and only ventures out onto the streets after dusk. He appears in just three stories – ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841), ‘The Mystery of Marie Roget’ (1842) and ‘The Purloined Letter’(1844) – but these provide an excellent template for all writers in this particular genre. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle said, ‘Each [of Poe’s detective stories] is a root from which a whole literature has developed… Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?’ Dorothy L. Sayers, the creator of Lord Peter Wimsey, commented that ‘ ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ constitutes in itself almost a complete manual of detective theory and practice’.

Film adaptations of Poe’s works were produced as early as 1908 when a silent version of ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’ appeared. The most notable Poe films remain the series produced by Roger Corman starring Vincent Price produced in the 1960s: The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962), The Premature Burial (1962), The Raven (1963) and The Masque of the Red Death (1964).

Today Poe’s reputation as a great and influential writer is firmly established, resting mainly on that selection of mesmeric tales of terror and his fascinating lyric poetry. His work continues to ensnare, fascinate, disturb and inspire readers.

Books associated with this article

The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe