Try a Little Tenderness: Lady Chatterley’s Lover

‘Try a Little Tenderness’: as Lady Chatterley’s Lover comes to Netflix, Sally Minogue looks at both novel and adaptation.

I always labour at the same thing, to make the sex relation valid and precious, instead of shameful. And this novel is the furthest I’ve gone. To me it is beautiful and tender and frail as the naked self is, and I shrink very much even from having typed it. [Collected Letters, 1962, p. 972]

Thus D. H. Lawrence on his final novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. And make of it what you will, its one undeniable achievement is, as its author desired, to make the sex relation valid and precious in a way that certainly had not been achieved in fiction before that, and has seldom been since. There’s an interesting elision and ambiguity in that statement by Lawrence too. When he goes on ‘To me it is beautiful and tender and frail’, his ‘it’ is referring first to his novel. But it can also refer back to the sexual relation itself. It is the ‘beautiful, tender and frail’ in the sexual scenes in the novel that I want to concentrate on here – in part because I think this is what is missing in the latest film adaptation. [In doing so I put to one side potential criticisms of the novel, which I’ve addressed more fully here.

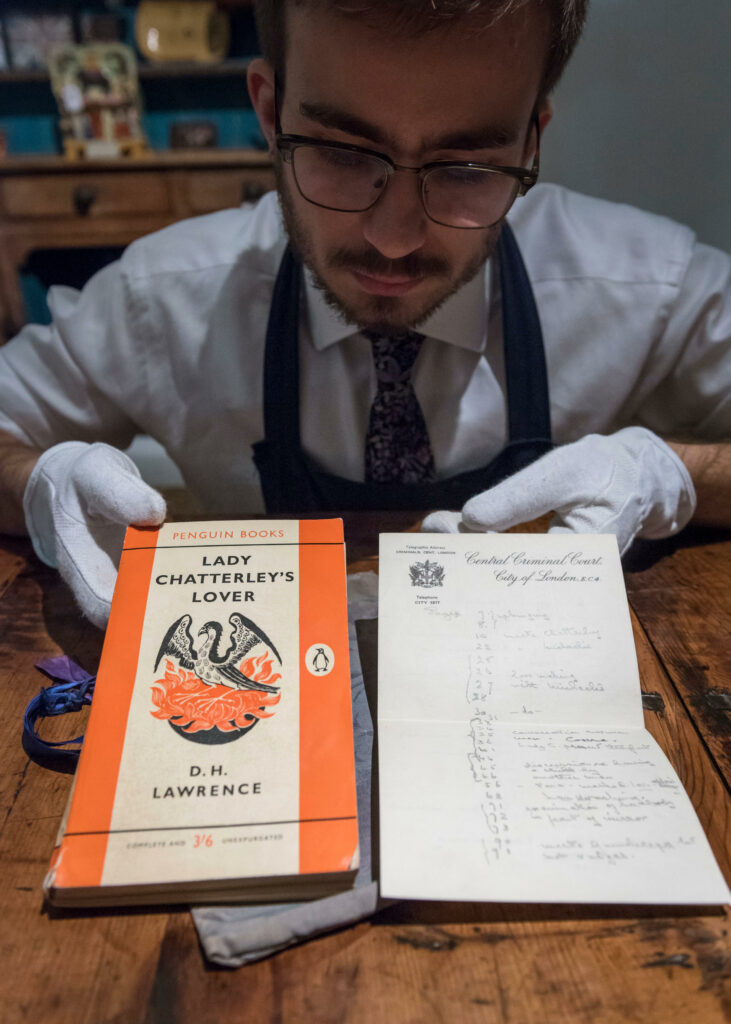

The Judge’s copy from the 1960 obscenity trial

Looking back at my own previous blogs on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, one remark of mine strikes me: ‘The [Obscenity trial] case revolved around not the act of sex itself, but the description of that act in language’. And I see too that, reviewing the Jed Mercurio television adaptation (BBC One, 2015), I worry away at its failure to use Lawrence’s explicit language. There’s obviously a motif here in adaptations. Lawrence’s language provides more of a problem to the film adaptor than the sexual scenes themselves. I’ve heard two interesting discussions about the Netflix adaptation on the radio recently. Both were in the context of the film’s 15 Certificate – a certification which reminds us of the cultural and moral shift since the 1960 Obscenity trial. Then, the prosecuting Counsel wondered if the jury’s ‘wives or servants should read’ the novel; now a 15-year-old can see the film version. But here’s the rub, and the nub. Was that rating angled for? The PM programme discussion (Radio 4, January 3rd, 2023) seemed to suggest that the explicit language was more problematic than the representation of sexual acts in the granting of certification. Natasha Kaplinsky, the new, and first female, President of the British Board of Film Classification, when asked on Woman’s Hour (Radio 4, January 12th, 2023) about that 15 rating said of the nudity in the film, ‘it is playful, romantic – it’s not sexual’. What?? Sound of Lawrence grinding his teeth whilst turning in his grave.

The BBFC, no doubt aware that the 15 rating for Lady C might raise some eyebrows, has issued some interesting explanatory notes. Their guidelines on sex for this rating allow ‘sexual activity … without strong detail’ and ‘There may be strong verbal references to sexual behaviour’ but ‘repeated strong references, particularly those using pornographic language, are unlikely to be acceptable.’ They give Lady Chatterley’s Lover the thumbs up because ‘there is no pornographic language’ (though ‘an occasional use of “f**k”’ is allowable). The asterisks are the BBFC’s, not mine. And that highlights the absurdity involved in all of this. If the BBFC itself is reduced to asterisks when explaining its policy about ‘strong sexual references’, we are all lost. They do make several good points about the film’s depiction of sexual activity in the context of today’s norms, noting that people ‘are more accepting of depictions of sex that are consensual and respectful’ – as indeed this film’s depictions are, according with those in the novel. This makes it all the sadder that one key element in that depiction is left out of the film: the use of explicit sexual language between Connie Chatterley and Oliver Mellors, a continuation of Mellors’ own natural dialect (and, narratively, a sign of their deepening relationship).

They meet first when Connie has been freed from the care of her husband by Mrs Bolton and, feeling her freedom and also looking for it, she goes out into the March wind to look for daffodils by the keeper’s cottage:

Little gusts of sunshine blew, strangely bright, and lit up the celandines at the wood’s edge, under the hazel-rods, they spangled out. And the wood was still, stiller, but yet gusty with crossing sun. The first windflowers were out, and all the wood seemed pale with the pallor of endless little anemones, sprinkling the shaken floor.

Remember this was written in Italy; but oh! to be in England. No-one carries that close natural observation in his head as well as Lawrence. It is important, because it authenticates what is to come. There’s a certain amount of fencing between Connie and Mellors as she seeks to appropriate the hut next to the rearing pheasants. She is at this moment still mi’lady, asserting proprietorial rights. But as they converse, they are brought into conflict, and so connection, through the difference in their language:

She looked at him, getting his meaning through the fog of the dialect.

‘Why don’t you speak ordinary English?’, she said coldly.

‘Me! Ah thowt it wor ordinary.’

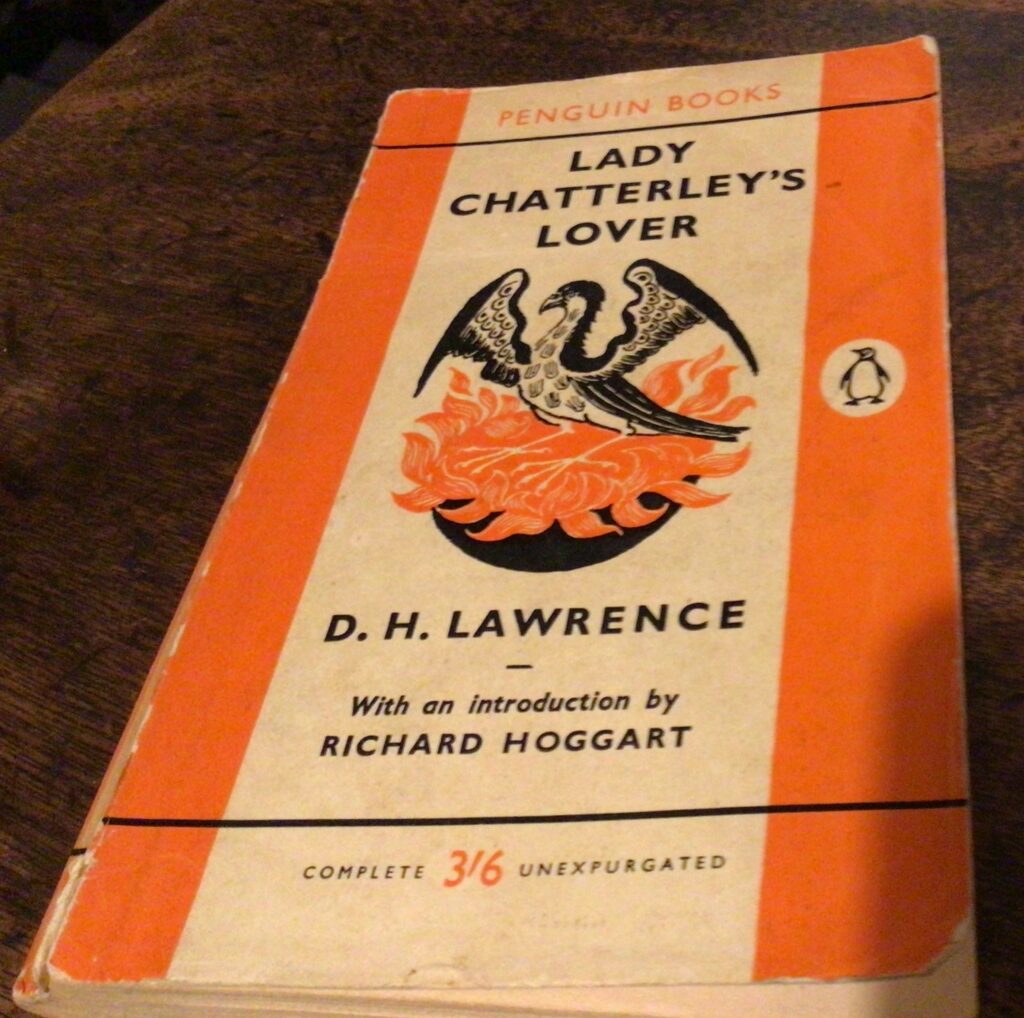

Sally’s copy of the revised 1961 edition

There is a clear progression in their eventual sexual encounters, the first notably prompted by their closeness over the baby chick amongst the many the keeper has been rearing. In this first love-making, Connie is passive and ‘The activity, the orgasm, was his, all his’ – though it is a scene imbued with gentleness, prompted first by the baby chick. The second encounter rouses Connie to ‘a new nakedness emerging’, as Mellors almost worships her body, but still ‘she is a little left out’. The third takes place not in the hut but in the open, in a thicket of the wood, and here both come together. Leaving aside Lawrence’s irritating obsession with simultaneous orgasm, nonetheless his description here of Connie is both beautiful and ground-breaking. If we allow ourselves to be open to Lawrence’s writing here, we can admire a prolonged representation of female sexual pleasure which is rare indeed. And the relationship between her and her lover is equally balanced. Consensual and respectful: yes. Further meetings in and out of the hut bring them closer both sensually and personally, and key in it is the language used between them. Again, Mellors’ dialect is central in the way the barriers between them, of class and gender, are washed away, as she learns his language:

‘Tha’ mun come one naight ter the’cottage, afore tha goos; sholl ter?’ he asked.

‘Sholl ter?’ she echoed, teasing.

He smiled.

‘Ay, sholl ter?’ he repeated.

‘Ay!’ she said, imitating the dialect sound.

‘Yi’ he said.

Thus they talk, teasing and caring for each other, and this exchange leads into what the BBFC are still calling ‘pornographic language’:

‘Th’art good cunt, though, aren’t ter? Best bit o’ cunt left on earth. When ter likes! …

‘What is cunt?’ she said.

‘And doesn’t ter know? Cunt! It’s thee down there; and what I get when I’m I’side thee, and what tha gets when I’m I’side thee; it’s a’ as it is. All on’t. …

‘Tha mun go, let me dust thee’ he said. His hand passed over the curves of her body, firmly, without desire, but with soft, intimate knowledge.

Writing about sex is difficult, and can easily be made to seem ridiculous; it was and remains so. Only Joyce at that time was trying to express in language what Lawrence was trying also to express. The results were quite different, but the artistic bravery was the same. It’s hard for us now to realise just what extraordinary acts of the imagination these were.

The 21st descendants of these writers from a century ago are perhaps the gay/queer writers who explore sexuality from their own perspective but in doing so open up a world to all readers. I am thinking particularly here of Seán Hewitt’s memoir All Down Darkness Wide which with a coruscatingly honest but at the same time deeply lyrical use of language tries (I think he would like that ‘tries’) to understand, explore, express his own desires amidst the depths of grief. In fact in this work desire and grief are one. Here’s Hewitt in the opening of his memoir:

At the centre of the cemetery, flowing down into a square pool between the laid-out gravestones, a little spring uncovered in the eighteenth century runs on, unperturbed, trickling over the luminous green growths of liverwort and algae on the bricked-up far wall of the plot. And on this January night, when the only living inhabitant of the graveyard is a single man drinking from the spring, anyone might come down and walk under the silvered boughs, hearing that gentle babbling stream, and imagine all the souls here, cooped up in the soil, passing from root to root, moving slowly in the underworld of the earth.

Our author is in the cemetery – notionally, and sometimes actually – for sexual pleasure, and indeed concomitant pain. This natural description is intimately part of that, feeds into it as the stream trickles through his whole introductory narrative. I think Lawrence would have been amazed, but I like to think also delighted, at the extreme reaches of sexual experience such writers express. He would certainly have admired the way language has opened. These writers might even have helped him to understand himself better. But they also surely understand themselves better because of his example.

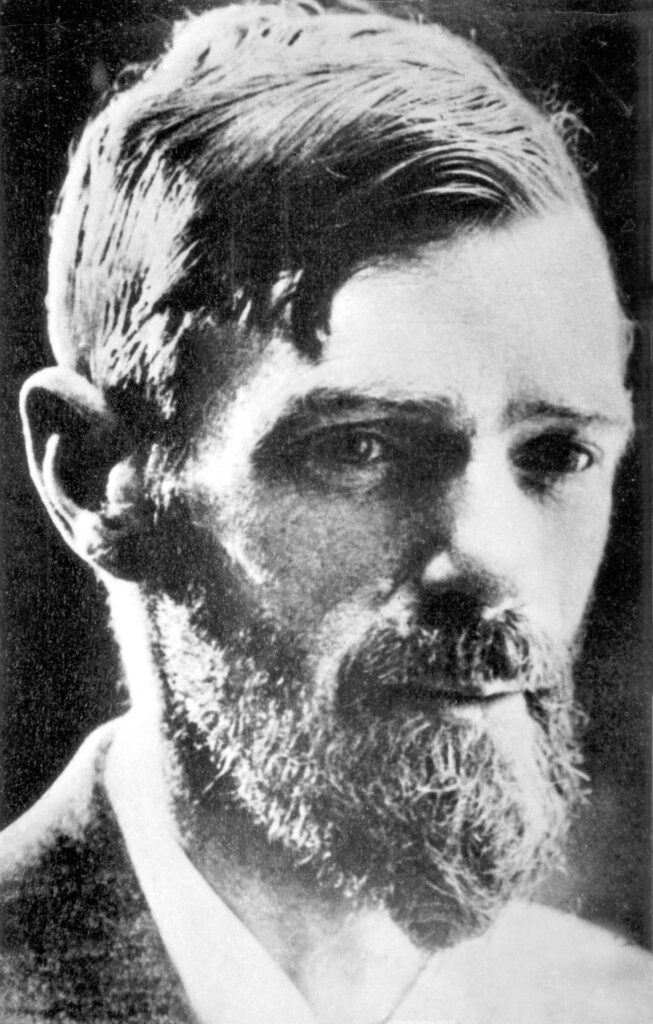

D.H. Lawrence 1929

Lawrence’s heroic struggle as a writer was with the forces of censorship. No wonder he shrank as he typed his final novel, since he knew what ranks of moral judgement, backed by the law, were ranged against him. His words were hostages to fortune, and he rightly feared for them and for the freight they carried. A novel about class as well as sexuality, with the two interwoven; about a woman’s sexuality as well as a man’s; about the deep wound inflicted by the First World War on those who fought in it; about the cruel forces of industrialisation ranged against the beauty of nature; about the power of ordinary spoken language, dialect even, to describe not just desire but the love that went with it. A book about the inner consciousness of a gamekeeper! Even as Lawrence wrote, he knew that there would be difficulties with publication. This applied from his earliest works, far less explicit than his final novel. In Britain, his major novel The Rainbow was prosecuted in an obscenity trial in 1915 and subsequently copies were seized and burnt by the Customs authorities. Burnt! It would not be freely published in Britain until 1921. Women in Love, its sequel, was published first in the United States, dogged by the publication problems of The Rainbow. It too came out in Britain in 1921. His final novel could be published only privately, in Italy, in 1928, and in 1929, in France. The unexpurgated version appeared in the United Kingdom only in 1960, triggering the trial for obscenity against it and changing the force of the obscenity laws for good.

It seems to me that in spite of these strides made in the written expression of sexuality, helped in part by Lawrence’s novel, those insidious forces of censorship are still at work as long as the BBFC is still talking about the language Lawrence used as ‘pornographic’. The use of the word ‘cunt’ used lovingly is still apparently more threatening to our moral lives than scenes of gross physical violence on film. I don’t know, but I suspect that, regarding language, there was some self-censorship going on in this Netflix film (which also has a general release, hence the need for certification) and as a result the sexual scenes are reduced often to a sort of soft-focus soft porn. The one scene which does work beautifully in the film is that where Mellors and Connie cavort naked in the rain, Emma Corrin and Jack O’Connell both making a very good job of not being ridiculous by making this a thoroughly playful, and a loving, scene. It’s the scene which, in the novel, is followed by the two lovers’ threading wild flowers in each others’ pubic hair and round their bodies, a scene oft ridiculed, but in fact an extension of those rapturous descriptions of the natural world elsewhere in the novel. Here Mellors revives their earlier conversation revolving round John Thomas and Lady Jane as their names for penis and vagina. His lightness of being and fancifulness here is paradoxically part of the deepening of a relationship which by now has become necessary to both of them:

He had brought columbines and campions, and new-mown hay, and oak-tufts, and honeysuckle in small bud. He fastened fluffy young oak-sprays round her breasts, sticking in tufts of bluebells and campion: and in her navel he poised a pink campion flower, and in her maiden-hair were forget-me-nots and woodruff.

‘That’s you in all your glory!’ he said. ‘Lady Jane at her wedding with John Thomas.’

Really, what could be more innocent? And a scene that might be both a welcome relief and an education to today’s fifteen-year-old. It is a scene of tenderness – another of the alternative titles for the novel.

Ah well, all’s one. This last novel which Lawrence cast almost despairingly before a limited public, fearful for its frailty and beauty, is still very much with us, still central to our cultural imagination, and its language is there for us all to read. And what a novel it was for him to go out on.

Wordsworth publishes all of the D. H. Lawrence novels mentioned and more.

Seán Hewitt, All Down Darkness Wide, Jonathan Cape, London, 2022

The film of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was made for Netflix in 2022 but also has a general release. It is directed by Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre from a screenplay by David Magee, adapted from the novel.

As I often seem to depart from the views of film critics, an alternative view of the film by Peter Bradshaw for The Guardian, which praises it as ‘this idealistic, moving French version’, can be found at amp.theguardian.com.

Main Image: Emma Corrin. Jack O’Connell., “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” (2022). Photo credit: Netflix / PictureLux / The Hollywood Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Image 1 above: A technician presents “The Judge’s copy from the 1960 obscenity trial, annotated by him and his wife” Credit: Stephen Chung / Alamy Live News/ Alamy Stock Photo

Image 2 above: Sally’s own copy of the revised 1961 edition. Credit: Sally Minogue

Image 3 above: Portrait of D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930) by Ernesto Guardia 1929 Credit: Photo 12 / Alamy Stock Photo

Books associated with this article