Woman of Stone

M.R. James, Mark Gatiss, and the Evolution of the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas Woman of Stone

‘The ghost is innately conservative,’ Professor Clive Bloom once wrote, in an uncompromising essay on M.R. James. A bold claim in gothic theory, it makes perfect sense when you think about it. ‘Ghosts tell us of stability and permanence,’ Bloom argued, ‘In a world of rapid change they speak of the unchanging and the traditional.’ Think how many national monuments and stately homes have ghosts attached to them. Even Buckingham Palace has a spectral monk and the unquiet spirit of Edward VII’s Private Secretary, Major John Gwynne, who shot himself after his marriage failed. Ghosts are a big part of our national heritage, appearing in all the guidebooks. And while terror might sell tickets, the apparitions floating around the Tower of London and Windsor Castle never do any real harm; they are part of the charm of the old buildings, adding atmosphere and character. More mythic than macabre, these are friendly ghosts, part of an idealised and nostalgic England: seeped in tradition, eccentric, and warmly gothic, the way that a Hammer film on TV feels like an old friend or, indeed, the BBC’s Ghost Stories for Christmas…

Bloom’s critique of James was that his ghost stories were similarly ‘conservative’, failing to move beyond traditional middle-class ‘literary’ aesthetics and resistant to interpretation despite being written during the revolutionary era of experimental Modernism. But then James was in every way a pillar of the English establishment. The son of a clergyman, he was educated at Eton, becoming a don and then provost at King’s College, Cambridge; he spent his life cataloguing illuminated manuscripts, editing apocryphal gospels, and bicycling to sites of historical interest, just like his doomed protagonists. This was not a man likely to push the boundaries of literary form. Instead, James looked back to the golden age of the Victorian ghost story, with a particular love of J. Sheridan Le Fanu. To Bloom, he was just a ‘psychic entertainer’, which was a label James could probably have lived with, later writing of his stories: ‘If any of them succeed in causing their readers to feel pleasantly uncomfortable when walking along a solitary road at nightfall, or sitting over a dying fire in the small hours, my purpose in writing them will have been attained.’ And isn’t this the point of the ghost story? Le Fanu called it ‘a pleasing terror.’ This was all just a bit of private fun, written once a year to be read aloud to students in his rooms on Christmas Eve by the light of a single candle, and not originally intended for publication. He never wrote in any other genre of fiction. Woman of Stone

And in delivering these tales on Christmas Eve, James himself was already joining a much older tradition, whether we start it with Dickens’ Christmas stories or go all the way back to the Neolithic campfire tales of the winter solstice festival of ‘Yule’. As the humourist Jerome K. Jerome playfully wrote of it, ‘Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet around a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories … It is a genial, festive season, and we love to muse upon graves, and dead bodies, and murders, and blood.’ I think we can all agree on that, especially those of us from large families. It is a national tradition upon which we look with both pride and affection, and although the medium may change the message remains the same. Christmas, even more than Halloween, is a time for ghosts.

Now, this is a tradition the BBC has been upholding for decades, scarring generations for life with their Ghost Stories for Christmas. The series has always leant heavily upon the writings of M.R. James, from the original films directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark in the seventies to the twenty-first century revival ably helmed by Mark Gatiss. Brilliant though this series undoubtedly is – my family binges the BFI boxset every Christmas – it could equally be charged with being somewhat ‘conservative’ given its authorial bias. Woman of Stone

‘Whistle and I’ll Come To You’ 1968

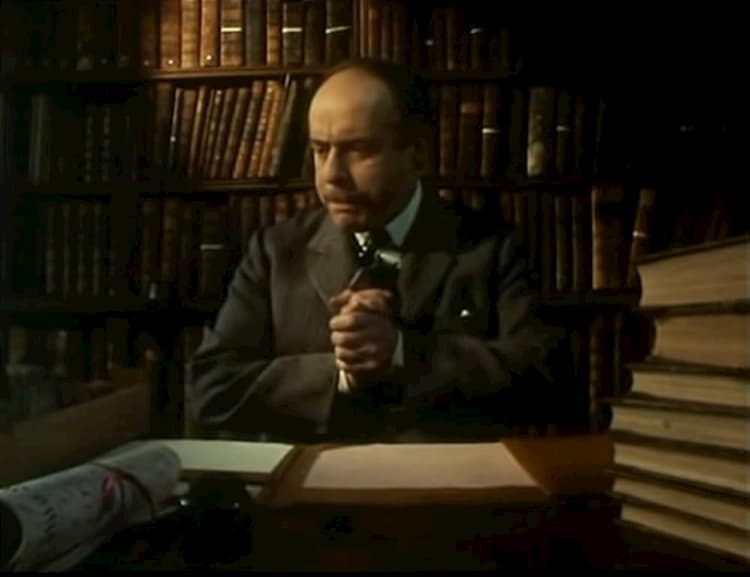

Film historian Jonathan Rigby credits Tony Richardson with directing two James stories for the BBC in 1954, Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook and The Mezzotint, but I confess I can’t find any record of these. After Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon (1957), a film version of James’ ‘Casting the Runes’ released by Columbia, the BBC’s first foray (as far as I know) into his fiction was Whistle and I’ll Come to You, directed by Jonathan Miller for the arts documentary series Omnibus. First broadcast in May 1968, this beautiful black and white adaptation starring Michael Hordern as the sceptical Professor Parkin both predated and inspired the Christmas series. Its success prompted the Controller of BBC One, Paul Fox, to greenlight a proposal by documentary director Lawrence Gordon Clark to adapt another James story for Christmas Eve 1971, The Stalls of Barchester starring Robert Hardy as an ambitious and impatient choirmaster who murders his ancient archdeacon to accede to the position, only to be haunted by a black cat and a hooded figure that resemble medieval choir stall carvings. James’ narrator becomes ‘Dr Black’ (Clive Swift), an academic cataloguing the library of the fictional ‘Barchester Cathedral’. Robust viewing figures and unanimous critical praise guaranteed a series resulting in A Warning to the Curious (Christmas Eve, 1972), Lost Hearts (Christmas Day, 1973), The Treasure of Abbot Thomas (December 23, 1974), and The Ash Tree (December 23, 1975). With inspired use of real locations – such as Norwich Cathedral for Barchester, The Shipwrights Arms at Wells-next-the-Sea (A Warning to the Curious), and Ormsby Hall (Lost Hearts) – crisp period detail, jump scares and brooding gothic atmosphere, pitch black humour, and understated performances by exceptional British character actors like Hardy, Swift, Peter Vaughan (A Warning to the Curious), and Michael Bryant (The Treasure of Abbot Thomas), Clarke created the template for the modern British television ghost story, much-copied but arguably never bettered. By 1975, Clarke’s short films had, themselves, become a Christmas tradition. As novelist Angela Carter wrote in the Radio Times that year: ‘The annual M.R. James adaptation is a television tradition, now: a more than satisfactory replacement for tales whispered round the hearth.’

I still remember watching these stories as a kid with my parents when they were first broadcast. Television was a different experience back then. There were only three channels which usually stopped transmitting around midnight. These ghost stories were the last thing we watched before bed, as the open fire in the living room died down. You retired to a cold bedroom trying not to think about the pale and wheezing Ager clawing at Paxton’s suitcase or the hooded figure on Archdeacon Haynes’ staircase, but the more you tried the banish the images the more vivid they became. I owe Clarke a lot of childhood nightmares, as well as a career specialising in gothic literature.

But in 1976, the series deviated from James for the first time, dramatising Dickens’ 1866 Christmas ghost story ‘The Signal-man’, one of the finest supernatural tales in the English language. The film starred Denholm Elliott as the title character, haunted by a mysterious spectre at the mouth of a railway tunnel by his remote signal box, and was hailed by critics and viewers alike as an instant classic. This was a compromise between series producer Rosemary Hill, who wanted to take a more contemporary path, and Clarke, who preferred period drama, as both loved Dickens’ story. This could have taken the series in a new direction while maintaining the popular period setting, opening the possibility of introducing ghost stories by other Victorian and Edwardian authors to a new audience. Instead, Hill got her way the next year with an original screenplay by Clive Exton, Stigma, a folk horror with a modern setting involving stone circles and witches. This was the last of the series to be directed by Clarke and was not well received by viewers, who wanted a period ghost story. Clarke left the series, which Hill killed the following year with another contemporary story, The Ice House, by John Bowen, who had previously written The Treasure of Abbot Thomas, which was opaque and underwritten to the point of incomprehensibility. Hill should have learnt the lesson of Hammer Films, who went bankrupt after a disastrous attempt to update the traditional gothic in box office flops like Dracula AD 1972 and To the Devil a Daughter. Woman of Stone

‘The Stalls of Barchester’ 1971

Clarke took M.R. James to ITV in 1979, directing an eerie and unsettling updated version of ‘Casting the Runes’ for the ITV Playhouse series starring Jan Francis and Iain Cuthbertson with a script by Clive Exton. But the show went out in April despite being set in the depth of winter. The BBC, meanwhile, returned to source with another Omnibus presentation the same year broadcast on December 23, made in the spirit of Clarke’s films. Schalcken the Painter, directed by Leslie Megahey, was a disturbing and sexually charged adaptation of Le Fanu’s ‘Strange Event in the Life of Schalken the Painter’ (1839), starring Jeremy Clyde and Maurice Denham as Dutch Golden Age painters Godfried Schalcken and Gerrit Dou. Megahey’s film offers a glimpse of what might have been had Clarke stayed at the tiller while steering away from James. Less well-known than the other seventies BBC Christmas ghost stories (and not part of the series), Schalcken the Painter remains sinister and visually stunning, being shot and lit like a series of Vermeer paintings. There was a BFI DVD release which is well worth tracking down.

The BBC would not revive A Ghost Story for Christmas until 2005, again returning to M.R. James with A View from a Hill, directed by Luke Watson and broadcast on BBC Four on December 23. This was followed by James’ Number 13, directed by Pier Wilkie and shown on December 22, 2006, again on BBC Four, before the series again stopped.

Whistle and I’ll Come to You, a reimagining of James’ original story by Luther creator Neil Cross, was broadcast on BBC Two on Christmas Eve 2010. With a haunting performance by John Hurt, a shy, retired academic revisits the seaside hotel where he and his wife honeymooned, having just placed her in a care home due to advanced dementia. The film manages to retain the essence of James’ story while taking it out of a whole new door. The climax scene is utterly terrifying yet deeply moving. Critics were not impressed by the modern setting and deviation from the original plot, but rightly praised Hurt for his portrayal of the introverted and lost Parkin.

Finally, Mark Gatiss (who had written and starred in the Clarke-inspired supernatural mini-series Crooked House on BBC Four over Christmas 2008) took the reigns for a fully-fledged revival, writing and directing James’ The Tractate Middoth, broadcast on Christmas Day on BBC Two in 2013. Coming up through the surreal sitcom The League of Gentlemen, Gatiss was a bankable screenwriter having co-created the successful BBC series Sherlock. A man who knows his British Gothic, Gatiss grew up with Clarke’s original ghost stories. Having presented the 2010 documentary series A History of Horror for the BBC, he was asked to host a documentary about M.R. James. He agreed to do this on the condition he could make an accompanying Ghost Story for Christmas, which had thus far failed to successfully relaunch. Gatiss understands James and Clarke, and his film returned to the formula perfected by the latter, staying in period with some excellent locations (such as Chetham’s Library in Manchester), and casting established British actors like Louise Jameson and Eleanor Bron alongside emerging new talent such as Sacha Dhawan (The History Boys, and the Master to Jodie Whittaker’s Doctor Who).

With Dr Who and Sherlock keeping Gatiss busy, we had to wait until Christmas Eve 2018 for another BBC Two Christmas ghost story. The Dead Room starring Simon Callow is a crafty blend of old and new. The story is original, but constructed around a stage actor presenting a long-running radio horror show musing to his producer about what makes a good ghost story as one begins to happen to him. His insights are all taken from James’ 1931 essay ‘Ghosts – Treat Them Gently!’ in which he set out a series of guidelines to write the perfect ghost story. One can sense Gatiss, who is a big fan of E.F. Benson for example, trying to find a way to retain the sensibility of the original Ghost Story for Christmas while at the same time moving beyond it, the way his friends Russell T. Davies and Steve Moffat had revitalised Dr Who. Though considerably better than Stigma and The Ice House, The Dead Room didn’t quite cut it and Gatiss made the more faithful Martin’s Close starring Peter Capaldi the following year (again shown on Christmas Eve), another M.R. James story. Then there was The Mezzotint (December 24, 2021), albeit with a more sensational climax than James’ original, and Count Magnus (December 23, 2022). Last year, however, was different. We didn’t get an M.R. James story. Woman of Stone

‘The Signal-man’ 1976

Lot No. 249 (Christmas Eve, 2023) is based on the short gothic story of the same name by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, first published in Harper’s Magazine in 1892. The choice smacks of Hill and Clarke’s move to Dickens’ ‘The Signal-man’ in 1976. Though daring to diverge from M.R. James, it’s still a period piece and the author is still a popular literary brand that viewers will know and accept through other costume dramas if not their own reading. And everybody loves Sherlock Holmes, right? (This isn’t a Holmes story, by the way.) Written in the wake of the British occupation of Egypt, the rise of modern Egyptology, and H. Rider Haggard’s 1889 novel Cleopatra, Doyle’s story is significant in being one of the first, if not the first, to employ the now familiar horror trope of the murderous reanimated mummy, in a plot not a million miles from Poe’s ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’. Gatiss makes good use of fin de siècle Oxford and the competing values of Decadence and Imperialism, with nice turns by Freddie Fox as the mummy’s master Edward Bellingham and Kit Harington (Jon Snow himself) as the starchily heroic Abercrombie Smith. If there’s a problem with the story, it’s that what was highly original in 1892 is downright clichéd today because of the subgenre it inspired. But that’s not the point. Gatiss was testing the waters to see if he could bring other authors into A Ghost Story for Christmas, and with Lot No. 249 he succeeded; Doyle’s story was the best-performing show on BBC Two on Christmas Eve. This year, he’s pushing the boundaries even more with Woman of Stone, an adaptation of E. Nesbit’s ‘Man-Size in Marble’ (1887), scheduled to be broadcast on Christmas Eve and starring Éanna Hardwicke, Phoebe Horn, and Celia Imrie as Nesbit herself.

Although best known nowadays for The Railway Children, Nesbit was a versatile and prolific author and political activist. She wrote four collections of horror stories published between 1893 and 1910, ‘Man-size in Marble’ appearing in the first, Grim Tales. In the story, a newly married and happy bohemian couple move to a cottage in the country that stands on the site of ‘a big house in Catholic times.’ The effigies of the original owners can still be seen in the local church:

…on each side of the altar lay a grey marble figure of a knight in full plate armour lying upon a low slab, with hands held up in everlasting prayer, and these figures, oddly enough, were always to be seen if there was any glimmer of light in the church.

The couple engage a local woman, Mrs. Dorman, as a domestic, and are delighted by her tales of ‘things that walked’ and of the ‘sights’ which ‘met one in lonely glens of a starlight night.’ But in October, she announces suddenly that she must leave before Halloween, apparently because of the figures in the church:

‘They do say, as on All Saints’ Eve them two bodies sits up on their slabs, and gets off of them, and then walks down the aisle, in their marble…’

‘And where do they go?’ I asked, rather fascinated.

‘They comes back here to their home, sir, and if any one meets them —’

What happens next, Mrs. Dorman will not say, but she is adamant that she won’t be staying… Woman of Stone

‘The Tractate Middoth’ 2013

Like Doyle, Nesbit is a reasonably well-known literary name as a children’s author (though less so since the Harry Potter generation), but I’d wager not many people who grew up with The Railway Children and Five Children and It know she wrote horror. Given the narrowness of vision when it comes to literary adaptation in film and television, turning one of her ghost stories into a primetime drama is cause for celebration among readers and literary historians. At last! – someone is looking beyond the same handful of famous writers and texts, which are filmed again and again, leaving us with dozens of versions of the same story, while once popular contemporaries of the likes of Dickens, Doyle and James are overlooked completely because culturally conservative executives are not willing to risk investing in ‘unknowns’. I use the term guardedly – unknown outside the academy and specialised publishing, let’s say, not or no longer household names. I say, let’s make them household names again! Let’s give the viewing public something different. Let’s inspire them to go out and read Grim Tales or something by Doyle that isn’t a Sherlock Holmes story. And as far as ghost stories are concerned, the long nineteenth century really was a golden age, with enough spooky tales to keep fans of period gothic terrified for years. Let us bask in the possibilities of what Gatiss might consider adapting next Christmas. I have suggestions…

Though ‘Man-size in Marble’ is Nesbit’s best-known and most frequently anthologised horror story, there is much more to be rediscovered: ‘John Charrington’s Wedding’, perhaps, in which the title character promises his future bride, ‘I believe I should come back from the dead if you wanted me!’ Then there’s the Poe-like ‘Hurst of Hurstcote’ or the chilling ‘From the Dark’. And in embracing a female author, Gatiss is also opening the door of the crypt to a large group of British women – from Romantic to Modernist – who made a significant contribution to the development of modern literary horror such as Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley (who wrote a lot more than Frankenstein), Charlotte and Emily Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell – ‘The Old Nurse’s Story’ is an obvious choice – Catherine Crowe, Margaret Oliphant, Charlotte Riddell, Amelia Edwards, Dora Sigerson Shorter, H. D. Everett, ‘Vernon Lee’ (Violet Paget), and May Sinclair. And for an American perspective on the female gothic, there are the subtle and elegant ghost stories of Edith Wharton.

‘Lot 249’ 2023

Then there are the Regency tales of terror from the likes of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine that so inspired Poe – stories like ‘The Vampyr’ by John Polidori, which predated Dracula by 80-odd years. And looking to contemporaries of Dickens, why Le Fanu’s ‘Green Tea’ – in which a clergyman may or may not be haunted by an ethereal demonic monkey – has yet to be adapted for television remains a constant mystery to me. There is Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s tale of haunted houses, gothic immortals and black magic, ‘The Haunted and the Haunters’, and Wilkie Collins’ ‘The Haunted Hotel’, set among the grim waterways of Venice. And, of course, there are Dickens’ numerous other ghost stories, most notably ‘To Be Taken with a Grain of Salt’, ‘To Be Read at Dusk’, and ‘The Hanged Man’s Bride’. And moving from the Victorian to the Edwardian, there are William Hope Hodgson’s tales of Carnacki the Ghost-Finder, only one of which has ever been adapted for television in a bold Thames Television project called The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes which ran for two seasons between 1971 and 1973, and which sought to do what I’m suggesting here by reacquainting TV audiences with lesser-known but equally enjoyable contemporaries of Doyle. (Occult detective Thomas Carnacki was played by Donald Pleasence.) I think people forget that Kipling was a prolific writer of ghost stories too, from the far-flung reaches of the British Empire to the horror of the Western Front – dark, morally ambiguous tales that might surprise readers more familiar with his imperial, patriotic side. Aside from The Turn of the Screw, the ghost stories of Henry James are rarely covered, although Mike Flanagan wove several into his excellent series The Haunting of Bly Manor. Lovers of M.R. James would find much in common with the stories of Oliver Onions, H.G. Wells, and E.F. Benson, and then there are the writers that H.P. Lovecraft designated, alongside James, ‘Modern Masters of Horror’: Algernon Blackwood, Lord Dunsany, and Arthur Machen, whose folk horror masterpiece The Great God Pan is long overdue for a decent TV or film adaptation. We might also argue that there remains a lot of mileage in Lovecraft’s short stories too, as his Cthulhu Mythos tends to inspire filmmakers who at the same time never manage a straight adaptation of his original work. I would very much like to see a loyal version of ‘The Dunwich Horror’ or ‘The Whisperer in the Darkness’.

I could go on, but you get the general idea. I think Mark Gatiss gets it too, and that we’re going to see some fascinating and audacious choices over the years ahead should A Ghost Story for Christmas continue under his watch. But whatever happens, one thing’s as certain as mince pies and mistletoe, and that’s that there will always be Christmas ghost stories. And why wait for the telly to catch up when you can read the originals? Books are always the best presents, after all, and ghost stories read at the right time will stay with you forever. As Le Fanu wrote in All in the Dark:

The student, as I have said, had a sort of liking for the supernatural, and although now and then he had experienced a qualm in his solitary college chamber at dead of night, when, as he read a well-authenticated horror, the old press creaked suddenly, or the door of the inner-room swung slowly open of itself, it yet was ‘a pleasing terror’ that thrilled him.

Happy Holidays, everyone. And watch out for those Christmas spirits…

NB Clive Bloom’s essay ‘M.R. James and his Fiction’ can be found in Creepers: British Horror & Fantasy in the Twentieth Century (London: Pluto, 1993), which Bloom also edited.

Publisher’s note: Our collection of Nesbit’s supernatural fiction ‘Man-Size in Marble and Other Grim Tales’ is due for publication in March 2025 and can be found here The title story is also included in our compilation Classic Victorian and Edwardian Ghost Stories, which can be found here

Main image of ‘Woman of Stone’ Credit: BBC/Adorable Media/Rory Mulvey.

All other images above copyright of the BBC.

Some of the previous episodes in the series can be seen here: A Ghost Story for Christmas – BBC iPlayer

Woman of Stone Woman of Stone Woman of Stone Woman of Stone Woman of Stone Woman of Stone Woman of Stone

Books associated with this article

Ghost Stories of Henry James

Henry James

Collected Ghost Stories

M.R. James

The Haunted Hotel & Other Stories

Wilkie Collins