The Nobel Prize in Literature

As the Committee of the Swedish Academy put the Nobel Prizes for 2021 behind them and begin to consider the nominations for 2022, Sally Minogue looks at some of the past winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Nobel Prize in Literature has always carried a unique thrill for me.

Perhaps it is because I think it is the one prize any writer would want to win: cryptic in its processes, often surprising in its choices, the announcement popping up when least expected, the name often unknown. Literature is given its proper place alongside Physics, Chemistry, Peace even! There is a pantheon there, but with no hierarchy. Creative brilliance is recognised, in the case of the sciences often many years after the original event; and occasionally that is the case with Literature too.

I say that any writer would want to win it. But Doris Lessing, the winner in 2007, door-stepped by the Press as she returned from shopping, on being told the news, cried ‘Oh, Christ!’. Her mood was cantankerous; but then her citation was for being ‘the epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny’, so she was allowed to be cantankerous – it was what she had won the Prize for! The Nobel lot were spot on about that divided civilisation, now much more clearly in evidence. Lessing’s work stretched right back to her key novel in 1962, The Golden Notebook, and we might see it as stretching forward to right now and ‘me too’. The Nobel plays a long game. Lessing, who died in 2013, has retained the distinction of being the oldest person, at 88, to have won the Literature prize.

Lessing’s reaction, as she gets out of a taxi to find a gaggle of reporters waiting, is available for all to watch on YouTube, and I urge you to sample it, not least for the enjoyment afforded by her companion (perhaps a relative) who looks completely nonplussed, as well he might since he is carrying a globe artichoke in one hand and a string of onions in the other. After some enjoyable exchanges with the gathered journalists, Lessing remarks, ‘I’ve won all the prizes in Europe, every bloody one, OK? So it’s a royal flush.’ This highlights one of the pleasures of the Nobel in more recent years, that winners’ responses can be captured on film, tv, or latterly social media. I remember being deeply moved by seeing television news footage of Seamus Heaney returning by plane to Ireland after his award of the Nobel Prize, 1995, had been announced. It could have been an airport in the 1950s. A small plane lands, Heaney comes down the shaky-looking steps, and is greeted by his farmer-brother on the tarmac with a tremendous hug. There was an absolute rightness about his being given that prize. The citation reads: ‘for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past’. Yes. Heaney and his wife Marie had been in Greece when the prize was announced, and, in those days before social media and mobile phones, even his children couldn’t contact him to let him know. As with Lessing off doing her shopping, there’s something appropriate about that. The importance was elsewhere. When he did have time to reflect, Heaney remarked – invoking another Irishman – ‘Oscar Wilde once said that the only way to avoid temptation was to yield to it. So here and now, I happily and gratefully yield to the temptation to believe that I am indeed the winner of a Nobel Prize’.

Three years earlier the poet Derek Walcott, a great friend of Heaney’s, had been given the prize. Walcott hailed from the tiny island of St Lucia in the West Indies, and extraordinarily that island can also boast a previous Nobel winner, William Arthur Lewis, who won the Memorial Prize for Economics in 1979 (Economics was added to the list of prizes in 1969 and is named as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Memory of Alfred Nobel, to distinguish it from the historic Nobel prize). Walcott and Heaney were the first prize-winners where I felt an intimate connection to them and their work, and a swell of pleasure at their awards, since I had read their poetry throughout my life. Both came from small, little-noticed communities; both wrote in the shadow of colonialism; both produced bodies of poetry of great lyricism and great import. Both had, in James Joyce’s words, flown by the nets of nation, whilst intricately expressing their own space in their own place.

Now Joyce himself is one of the great missing in the Nobel archive.

One can check that archive (www.nobelprize.org) to find out who were nominees for the Prize, and who nominated them, though with the proviso of an embargo of 50 years, so the nearest one can go back to is 1971. This archive makes for fascinating reading. Many people are nominated year upon year, some of them finally winning. But the most revealing thing is that amongst the nominees there are so many names one has never heard of. (Of course, this is also from time to time true of the Prize winners. There is a general cry of ‘Who?!’ ) Joyce was never nominated. He didn’t come within a whisker of the Nobel Prize. Today, as the centenary of Ulysses is celebrated globally, one thinks of him as an obvious candidate. But when he died in 1941, his was still a highly controversial name, with Ulysses still banned in many countries. Joyce himself, had he known, would probably have thought that not being nominated confirmed that he was doing something right. If he flew by the nets of nation, he also flew by the nets of approbation. But the money would have been useful! Another writer of his generation, Virginia Woolf, might also have been deemed a possible Nobel candidate. Again, no nominations. But in the case of Woolf, it was probably her gender that came into play. When Lessing won the Prize in 2007, she was only the 11th woman to do so since its foundation 106 years earlier. Only 16 of the 114 Literature laureates to date have been women [1]

The name that came straight into my mind when thinking of potential laureates of the first quarter of the 20th century was that of Thomas Hardy. While Joyce had no nominations, Hardy was

nominated every year from 1910 to 1914, and every year but one between 1920 and 1927 (he died in 1928). But he was always the bridesmaid, and never won the Prize. His near neighbours W. B. Yeats and George Bernard Shaw were the prize-winning brides in 1923 and 1925 respectively, both years in which Hardy was also nominated. But since the workings of the Swedish Committee are so closely shrouded, he may not even have known that he had been so often in the offing. To my mind, Hardy would have been a most worthy prize-winner, for his ground-breaking fiction followed closely by his important body of poetry, work that spanned the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, not just in terms of date, but in its challenge to norms. It seems surprising that Shaw should have been preferred to him. Had Hardy known that, he might have been rightly disappointed. Yeats, on the other hand, was a major poet, and another writer who now seems an obvious choice. One would hope, in the spirit of literary generosity, that Hardy might have bowed to the inevitability of Yeats. He might not have been best pleased though, had he survived till 1932, when John Galsworthy was the winner. More of him later.

In the end, of course, there’s a certain amount of nonsense in this.

A prize for the ne plus ultra is to deny the large sweep and embrace of imaginative writing, its multiplicity and a technical experiment, not to mention its huge range of languages which can be known only in translation to many audiences (and to the prize-giving Committee). Furthermore, the Nobel Prize in Literature sometimes goes to what we might consider work that is first and foremost serving another discipline. Bertrand Russell won it in 1950 ‘in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought’, and Winston Churchill won it only three years later ‘for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values’. No two thinkers could be more fully opposed than Russell and Churchill. But certainly both used language in powerful and elegant ways in their own causes. Those two examples might go some way to checking complaints that the Nobel is frequently used in the service of political causes. That may be true in each of the cases of Russell and Churchill, but awarding the Prize to one and then the other creates a moral balance. The same sort of balance is carefully managed between competing countries and cultures. I am concentrating in this blog on the Prizes awarded to English-speaking writers, and perhaps more closely on those awarded to British writers. But one of the things the Nobel Committee is highly aware of is cultural equity.

The Nobel laureates that Wordsworth publishes are of course determined by the strictures of copyright, and so they are in the cohort of 70 years ago and more. (The Nobel Prizes were inaugurated in 1901.) An early winner amongst Wordsworth authors is Rudyard Kipling. He won the Prize in 1907, and, at the other end of the scale from Doris Lessing, he remains the youngest laureate at the age of 41. Kipling’s citation is specific but comprehensive: ‘awarded in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author.’ Now that is a citation any writer might be proud of; it covers the ground. I expect Kipling would have particularly liked ‘virility of ideas’, a striking phrase, and a fitting one. By 1907, Kipling had written Departmental Ditties (1886), Plain Tales from the Hills (1888), Barrack-Room Ballads (1892), containing the poems ‘Mandalay’ and ‘Gunga Din’, The Jungle Book (1894) and The Second Jungle Book (1895), all derived from his experience in India. After his marriage and a sojourn in America, his next big work was Kim (1901), also drawing on his Indian experience, and still regarded as a major novel of the twentieth century, though it has been fought over by cultural critics and historians. Kipling was the first English-language recipient of the Prize, and the Swedish Academy noted that ‘in awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature this year to Rudyard Kipling, [it] desires to pay homage to the literature of England, so rich in manifold glories, and to the greatest genius in the realm of narrative that that country has produced in our times’. So Kipling carried the whole English literary tradition on his shoulders – another thing he would surely have been pleased about.

Kipling’s Prize, and his citation, carry overtones of Empire, reminding us that the Swedish Academy hasn’t always escaped the influence of its own cultural moment.[2] In the presentation speech in 1907, by C. D. af Wirsen, the Academy’s Permanent Secretary, Kipling is blithely lauded for speaking in the Empire’s voice as well as England’s. And as far as England’s voice is concerned, he takes on the working-class voice as well in Barrack-Room Ballads – and is praised for it thus, without irony, by the Academy: ‘Surely, there is hardly any greater mark of honour that can be given to a poet than to be beloved by the lower orders.’ The whole question about Kipling is whether he occupies another identity in the best sense, by understanding it completely and speaking in its true language; or whether he occupies it, in the colonial sense. The Academy’s remarks not only assume the latter but praise it. The value of Kipling’s work continues to be contested, sometimes bitterly, particularly in relation to its representation of India. I think that Kim goes well beyond the limitations of that debate, as do some of the poems and short stories. But even within the debate, Kipling’s works are significant to the understanding of our cultural history.

One might think the cultural balance had been redressed somewhat by the awarding of the Prize in 1913 to Rabindranath Tagore, the first non-European winner, who wrote in Bengali but also translated some of his own works into English. However, the presentation speech for Tagore goes to some lengths to claim him for Christianity and to dissociate him from ‘all that we are accustomed to hearing dispensed and purveyed in the market places as Oriental philosophy, from painful dreams about the transmigration of souls and the impersonal karma, from the pantheistic …’ Heaven forfends that we are seduced in that direction! Interestingly, Tagore’s was both a first-time nomination and he had only one nominator, Thomas Sturge Moore, an English poet and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (which qualified him to nominate). In the same year, 97 other members of the RSL nominated Thomas Hardy! W. B. Yeats (also on the Wordsworth list), the Prize-winner in 1923, was a great advocate for Tagore’s work and wrote the introduction to the 1912 English translation of Gitanjali: Song Offering (the accessibility of which was influential in the awarding of Tagore’s Nobel the following year). Yeats himself had several nominations in several years, before his eventual success in 1923 when he was nominated by the Nobel Committee itself. And yes, it was another year in which Hardy was nominated… Yeats’ citation is ‘for his always inspired poetry, which is a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation.’ So as Kipling’s prize was in part for England, Yeats’ was in part for Ireland. This becomes more pointed when we remember that Ireland had just achieved hard-won independence from England, through the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922. With a new Chairman of the Committee of the Swedish Academy for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Per Hallström, giving Yeats’ presentation speech, ten years on from Tagore pantheism has become acceptable, and ‘Celtic pantheism’ at that. It is glossed by Hallström as ‘the belief in the existence of living, personal powers behind the world of phenomena … [which] seized hold of Yeats’ imagination and fed his innate and strong religious needs’. The Celtic Revival features strongly in the speech, as indeed do the plays of Yeats. Yet in 1923, arguably the best of Yeats’ poetry was yet to come – the poems of The Tower (1928), including ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, ‘Meditations in Time of Civil War’, and ‘Among Schoolchildren; The Winding Stair (1933), including ‘In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth’ and Con Markewiecz’, ‘Coole Park’, and ‘Coole Park and Ballylee’ – at once personal and specific in their reference, and impersonal, almost vatic in their tone; and the self-reflective Last Poems (1936-39), including the valedictory ‘Under Ben Bulben’. The Modernist poet that we regard him as now had yet to be fully formed. Well, perhaps the Academy were far-seeing in putting their money on Yeats; certainly, he proved a good bet.

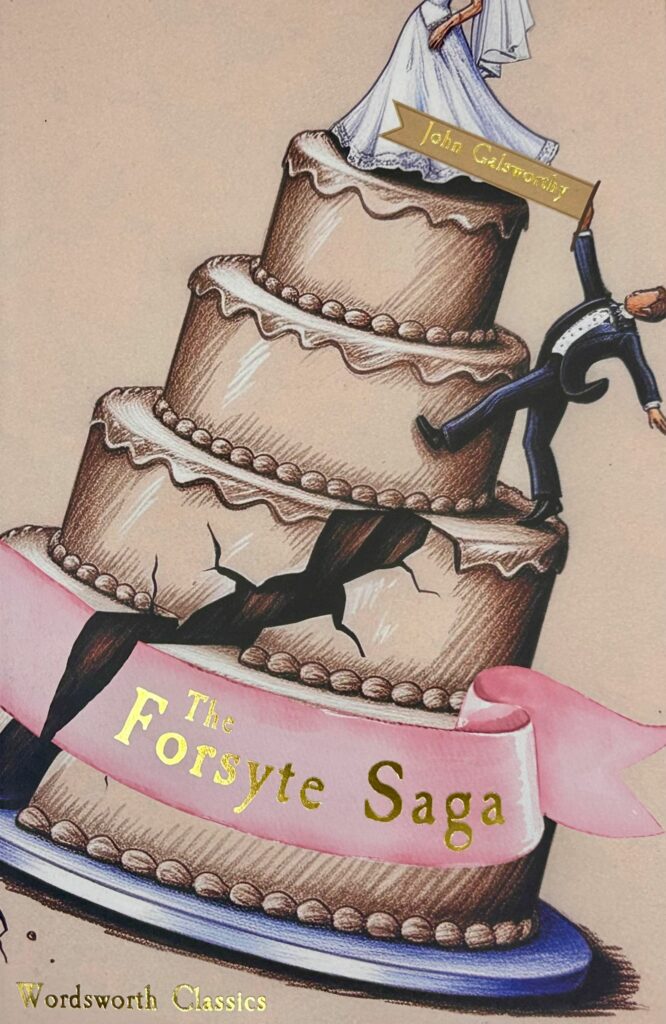

John Galsworthy is the third Literature winner on Wordsworth’s list, for the year 1932, perhaps something of a surprise, though only because he was such a popular author. But as the Nobel

Prize website itself notes, in the candidates for the Prize in Literature, ‘Household names alternate with totally unknown individuals, esoteric poets with the authors of best sellers, literary stylists with plain-spoken writers of non-fiction, youthful talents with writers whose oeuvre is complete.’ The Forsyte Saga certainly became a best seller, and, as occasionally happens with the Prize, it was singled out in Galsworthy’s citation: ‘for his distinguished art of narration which takes its highest form in The Forsyte Saga’. In fact, as the ambitious term Saga indicates, this was a body of work, consisting of three novels and two short stories or interludes. Galsworthy’s plays, which focused on social and moral issues, are not mentioned, though he was perhaps better known for these originally. The Forsyte Saga has consistently provided great narrative pleasure to readers since its first publication as a trilogy in 1922 (the same year that Joyce’s Ulysses was published). While it challenges and ironises Edwardian mores and attitudes, it is written in a traditional style that leads the reader into the complex relationships and histories within a family across several generations. It is a great read and has also been translated into two excellent television versions.

If I’d been around at the time, I wouldn’t have expected Galsworthy to win the Nobel Prize.

I would have expected Hardy too, and it’s a bit of a mystery to me that he never did – clearly not for want of being in the running. And speaking of running… It is possible to put a bet on the outcome of the Nobel Prize. I know this because I once put a bet on for a rather lesser prize, the Booker. In 2017, Paul Auster’s mammoth work, 4-3-2-1, was shortlisted for the Booker of that year. My dear friend and fellow blogger Stefania Ciocia and I read it at the same time and discussed it together. Personally, I was underwhelmed. Added to this, it took an awfully long time to read, and was a very heavy book to hold up in bed. It occurred to me that this – arguably least good – work of Auster’s output would inevitably win the Booker, perhaps on some misplaced notion of lifetime achievement, or as an accolade for his writing the whole damn thing in longhand. So to offset my labour in reading it, I thought I’d put a bet on 4-3-2-1 – that way at least I would reap some reward. I happened to be in Folkestone, and passing a Ladbroke’s (Ladbroke’s was my Dad’s favoured bookie’s for years), so in I went, to be greeted very cheerily, but with a modicum of the doubt when I asked if they had a book on the Booker. ‘Hmmm….’, the chap pondered, then plucked something from his memory. ‘I know we’ve got odds for the Nobel Prize for Literacy…’ I am glad to report that I didn’t betray a flicker of anything, indeed I was rather impressed, and flirted briefly with placing a bet in this altogether more prestigious and open race. ‘How do you know who’s up for it?’ He became a bit vague at that point but said he’d make a phone call about the Booker. Which he did – quite a lengthy chat – and came back to ask me how much money I might be placing. ‘10’ I said – then added hastily, in italics, ‘Ten pounds’. He gave me odds of 50-1 and I gave him my money. Poor old Auster: a rank outsider. The bookies knew what they were doing, and he didn’t win. Though in fact, and of course, I was very pleased that he didn’t. …….

Wordsworth Editions publishes the following Nobel-winning authors and their works:

John Galsworthy: The Forsyte Saga

Rudyard Kipling: The Jungle Book, The Best Short Stories, Just So Stories, Strange Tales, Kim, and Collected Poems.

W. B. Yeats: The Collected Poems

Wordsworth also publish many of the authors who were nominated.

Thomas Hardy is at the top of that list! Other nominated Wordsworth authors include: Anton Chekhov, G. K. Chesterton, Sigmund Freud, Henry James, Leo Tolstoy (anecdotally, it appears he didn’t come up to the Nobel moral ideal at the time), H. G. Wells, Edith Wharton.

Then there are those who were never nominated but would by every standard be thought worthy not just of nomination but the Prize! These include Joseph Conrad, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Franz Kafka, D. H. Lawrence, George Orwell, and Mark Twain.

Final footnote: I have just finished reading After Lives, the most recent novel by the 2021 Nobel Literature laureate, Abdulrazak Gurnah. It is a beautifully understated and compelling read. Gurnah’s citation was ‘for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents’. We have come a long way from Kipling speaking for the Empire.

Image: Bust of Alfred Nobel at the Nobel Prize Institute in Oslo, Norway. Credit: Norimages / Alamy Stock Photo

[1] Though one of the Academy’s early awards of the Prize was to Pearl Buck, in 1938 – when Woolf would still have been in contention.

[2] The 1938 Prize awarded to Pearl Buck, principally for her novel The Good Earth, about the life of peasants in China, might like Kipling’s now be open to questions about imperialist appropriation. But Buck herself fought hard for the recognition of Chinese fiction and storytelling, and her Nobel lecture is a paean to Chinese writers and their influence on her.

Books associated with this article

Collected Poems of Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling

Kim

Rudyard Kipling

Just So Stories

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book & The Second Jungle Book

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book & The Second Jungle Book

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book (Exclusive Edition)

Rudyard Kipling

The Jungle Book (Collector’s Edition)

Rudyard Kipling

The Forsyte Saga

John Galsworthy